Writers on photography typically emphasize the importance of the still image. This immobility twice distinguishes the medium: first, from the other distinctively modern visual media of cinema and television; second, from the temporality or ephemerality of whatever is the subject of the photograph. Only the photo stops time, holding everything caught in 1/500 of a second unchanged for all time. Only then can one really look at what was there, then; only in that time out of time can one really see and carefully reflect on what is being shown.

The writers of this blog are among those who have relied on this definition, not least because it does argue for the relative value of the medium while identifying one of its resources for understanding the world. Unfortunately, like the other writers, we were wrong.

Or more precisely, not wholly wrong so much as subject to overstatement. I say this because the time has come to consider the contrary thesis, which is that there are no still photographs. Likewise, we should consider how the temporal immobility of the photograph that we do experience is an illusion, perhaps one of those illusions that grow up around any medium as one of its effects and part of its distinctive habitus.

Such illusions become part of our common sense, and not least because they prove to be useful, so let me be clear that I am not trying to dismantle all of that. Of course, any photograph seems to be still, just as any movie seems to be moving while actually being a succession of still images. Likewise, I really do value the reflective space that is created by the photographic event, and a sense of having the time to look is an important part of that experience.

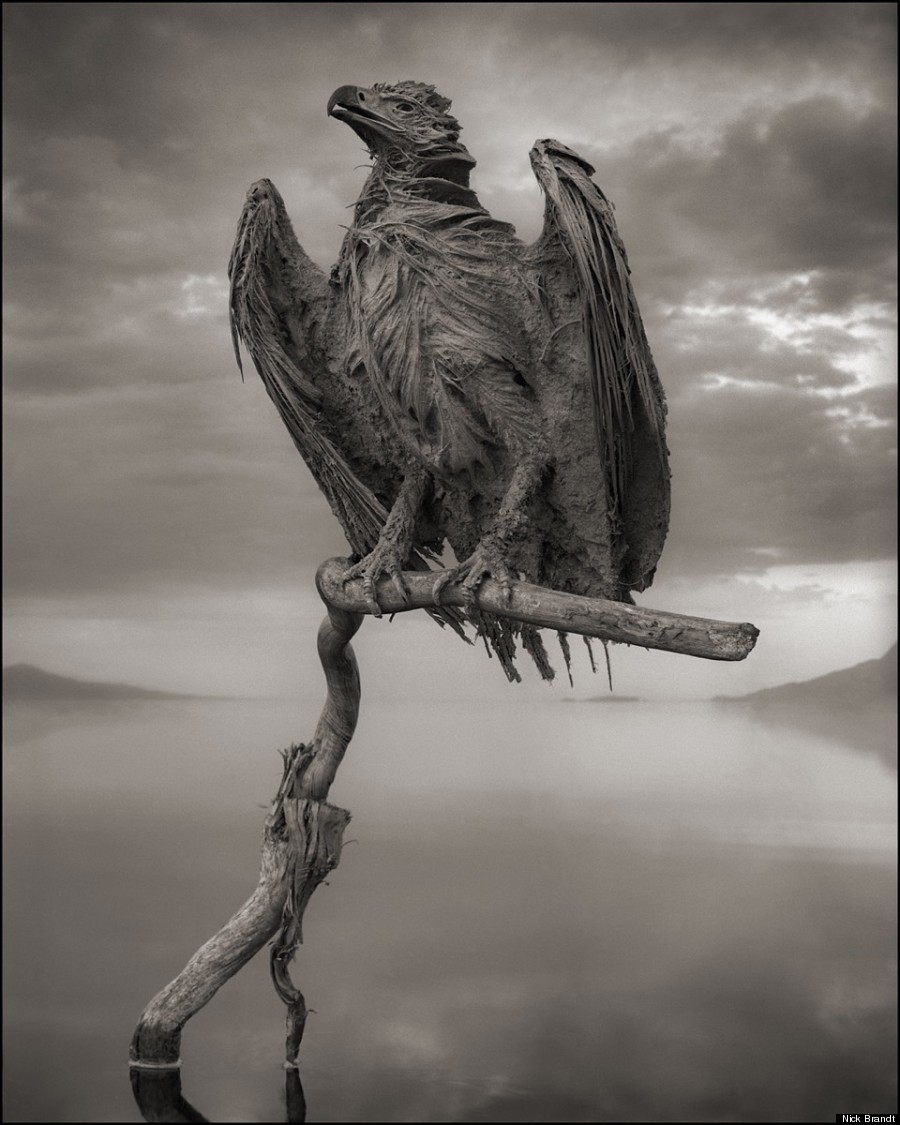

But what if we considered just how many ways the photographic image is already moving? One way to start would be to take a seemingly difficult case, like this one. Nick Brandt has taken photographs of animals that have become calcified after immersion in Lake Natron in Tanzania. As they attempt to air dry, the extremely high levels of soda and salt immobilize them. The result is at once horrific–they are buried alive in their own bodies–and aesthetic–they become ghoulishly “lifelike” statues.

So here you have an image where form and content are almost perfectly fused: both the bird and the photograph are forever fixed, still, incapable of movement. (As Aristotle would say, they can be moved but they cannot move themselves.) Although the water and sky at Lake Natron can change, they cannot change in the photograph, and the photographer’s skillful use of his black and white stock and tonal values support that sense of the scene. Like the bird, everything that once was capable of movement seems forever frozen by the medium–a medium created in a chemical solution that, like the lake, can harden time itself as it turns life into image.

But look at that bird. (After all, we have the time.) Can’t you see the flow of the water as it drained off the body, and the subtle air currents that wafted across it? Can’t you see the great wings poised as if for flight, and feel the powerful muscles ready to flex and contract? And doesn’t the pathos of the image come from that sense of flight and life interrupted? Without that sense of potential movement, the image would not be news; it would not even be an image, but only a unique particularity having no reference outside of itself. (Some would say that’s a definition of art, and there is an affinity there that I’ll not go into today.)

I’m running out of time today, so let me cut to the chase and summarize several senses in which I think the image always is moving. First and most obvious, the photograph always does refer to an ongoing eventfulness outside of itself. We call this the larger narrative or flow of events, or the situation or context, or the other images on the roll or otherwise taken before and after the single moment, etc. Sontag insisted that this was the only way in which photographs became meaningful, and that their tendency to stop time and fragment reality was a sure cause of all manner of cognitive, moral, and political problems. I think there are a great many problems with that formulation, but (as usual with Sontag) there is an important insight there: the photograph is never really apprehended in narrative isolation or out of time. Thus, there really are no still images, and to insist on the unique or transcendental character of the still image is to succumb to a characteristic illusion.

Another obvious and more recent sense of photography’s mobility is that the way in which images are used: whether material or virtual (and any one is both, in varying degrees), images are put in wallets, on phones, on walls offline and online, and they are shared, shuffled, liked, lost, found, repurposed, and otherwise used in varied ways that keep them moving in time as they acquire specific histories. The image can be temporarily fixed by the act of looking, an act it solicits, but that, too, is part of larger practices of selecting, substituting, discarding, and otherwise organizing and making sense of a continuously expanding archive.

A third sense of the never still image is that its meaning always depends on interpretation, and not least by multiple viewers. (Even if only one person sees the photograph and then burns it, the seeing and the burning alike depend on a sense of how others would see it and see it differently.) More to the point, the photographic image is inherently imaginative: even in its more realistic modality, it requires imagining others’ intentions, other ways of looking at the scene, as well as possible causes and possible consequences. The immobility allows time for such consideration, but that active shuttling between past and future is absolutely essential to the medium and particularly to how it is used as a medium for public culture.

Finally, and I really am running out of time here, photography is part of modernity’s continuous unfolding. Yes, that sense of modern civilization is itself a myth, but a powerful one. (Even getting “bombed back into the stone age” does no more than reinstate the myth: we might have to start over, but there is only one direction to go.) Like modernity itself, any photograph is a slice of time that is projected into the future: by becoming a record of what instantly is past, it can in fact be moved forward into the next moment and the next, always still present in a world forever pitched toward a future just beyond the now. After all, why else take the picture?

So there is more than one sense in which there are no still photographs. I would say that each of those definitions of the image can serve some of the same purposes that were handled by emphasizing its temporal immobility. The next step might be to endorse a dialectical movement, but let me suggest something else instead. Whether still or never still, immobile or ever activating, any revelation will come not from that fact alone but rather how it can be the basis for artistry and insight. Whatever the theory, everything still depends on who takes the photograph and what we do with it.

Photographs by Nick Brandt and Wojtek Radwanski/AFP-Getty Images. Brandt discusses the images in an interview at the Huffington Post.

0 Comments