The first day of school. It is a bourgeois, middle-class ritual. New clothes. New backpacks. A new start on a new year. And, of course, photographs; lots and lots of photographs, usually taken by parents and grandparents trained to recognize a Kodak moment when they see one—snapshots that celebrate the normative and gradual transformation of childhood to adulthood, marking it for future use and consumption with the tinge of nostalgia. “This,” the photograph says, “this is the way we were.” My family photo albums are filled with such images. And I cherish them, even though I know the many crises and unhappy moments that they help to repress and erase from memory and family history.

Capturing the first day of school is also a photojournalistic ritual, especially in local newspapers that regularly mark and celebrate the various cycles of the calendar: fall harvest, winter holidays with families meeting in reunion and engaging in spiritual observances, spring break renewal and the planting of new crops, summer fun on the beach, and on an on. And, of course, in an analogy with the photographs in our family photo albums, they frame and feature the habits of sociality and collective living that we want to observe and remember. The picture below appeared in a Washington Post slide show titled “Starting a New School Year” and consisting of eighteen photographs of elementary school children returning to school in the Washington D.C. area.

The photograph is in many respects typical of the other pictures in the slide show and of similar images one might find at many other newspapers. According to the caption they are a group of children “march[ing] to class” in a new school in suburban Maryland. Clean and orderly, they have learned early to walk in line at a common pace and to maintain their distance from one another (“no touching” is one of the rules we learn in kindergarten), and yet they are not automatons as each displays a somewhat unique personality in dress, attitude, and gesture. They are different and yet unified, obedient but not rigidly or obsessively so, and thus they evidence the habits of communal living a liberal democracy might want to inculcate among its citizens. And, of course, they are all African Americans being educated in a brand new school.

What caught my attention in the picture was the second girl from the left, dressed in a white blouse and taking what seems to be a playfully long stride, nipping at the heels of the boy in front of her. Where had I seen this image before? It took a few moments to register, but eventually I realized that it was vaguely reminiscent of Norman Rockwell’s “The Problem We All Live With.”

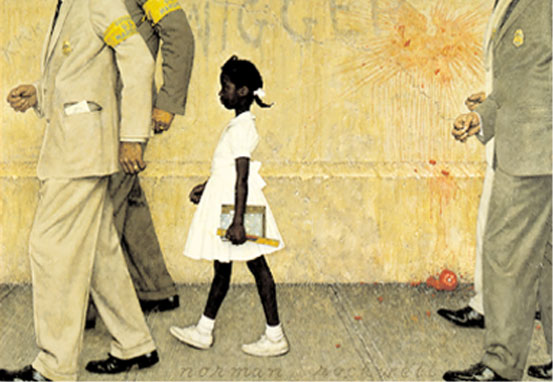

This painting first appeared in Look magazine in January 1964 but it depicts a scene from four years earlier when six year old Ruby Bridges was escorted by U.S. Federal Marshals to William Frantz Elementary School in New Orleans following a court order to integrate the schools in accord with the mandate of Brown v Bd. of Education (1954). White parents removed their children from the school and only one teacher—Barbara Henry—was willing to instruct Ruby. And for much of the next year Ruby was a class of one.

It is a painting, not a photograph, but in all likelihood it was artistically derived from one of several AP photos that show Ruby and her escorts entering the school. It is marked by strong contrasts of color: her dark skin and white dress, shoes, and hair ribbon stand out against the drab, muted colors of the suits and the wall. Notice in particular how the color of the suits connect the headless and anonymous marshals to the wall and the vicious word scrawled across it; the composition thus subtly identifies the institution now protecting Ruby with the institution that built the walls of segregation and contributed to her oppression and stigmatization. The wall is stained with the red of a tomato, the color of heated passion and blood, and thus a sign of the threat that abides outside of the frame of the picture. But amidst all of this is Ruby, pure, innocent, and, of course, looking forward to a new day–the first day of school with a new notebook and ruler in her hands. Note too that her stride is natural, but she walks faster than the escorts behind her, riding up on the feet of those in front of her. She is thus anxious to get to her destination, but she also holds herself in reserve, her emotions contained and constrained, another strong contrast with the scene around her. She is also an individual. And though there were hundreds of persons who orchestrated this moment in history, it is the lone individual standing up against the much larger forces of oppression that is featured (and remembered). It thus functions as part of the standard liberal antidote to political trauma, and in its own way it anticipates the photograph of the lone individual stopping a row of tanks in Tiananmen Square many years later.

There is no doubt a great deal more that can be said about this image. But it is its relationship to the contemporary photograph from the Maryland suburbs that most warrants attention here. For now we have seven children not one. We can assume that there are teachers directing the parade even though we don’t see them–a sign, perhaps, of established authority and effective leadership. Indeed, the photograph purports to be an ordinary (bourgeois, middle-class) first day back at school. It depicts an orderly scene in an open and brightly lit modern building. There is nothing that suggests even the hint of a threat; the vicious “n” word has been replaced by an affectively neutral and abstract term: “primary.” That the children are exclusively African American seems almost incidental—and more so when seen in the context of the entire slide show—as if the problems of equal educational opportunity among the races has been solved; and maybe in this school district they have, as this is a picture of a brand new school. But one has to wonder if there is not also a sense in which the photograph works to erase the image of the Rockwell painting from public memory, a substitution of the “real” for the “mythic.” Or if the word “erase” seems too strong, then perhaps the photograph mutes the mnemonic force of the earlier image, suggesting “that was then and this is now.” In either case, its reference to the conventional first day of school frames both images in a somewhat nostalgic register that underscores a myth of social progress: the idealism of the lone individual standing up to the forces of oppression (then) and the appearance of the happy-go-lucky first day of school (now).

If only that’s the way it truly was.

Photo Credits: Marvin Joseph/Washington Post; Norman Rockwell Estate

[…] the first day of school operate in a number of different interpretive registers, some of which we discussed last week, but none is more pronounced in the public media than their function as visual tropes of […]

[…] more here […]