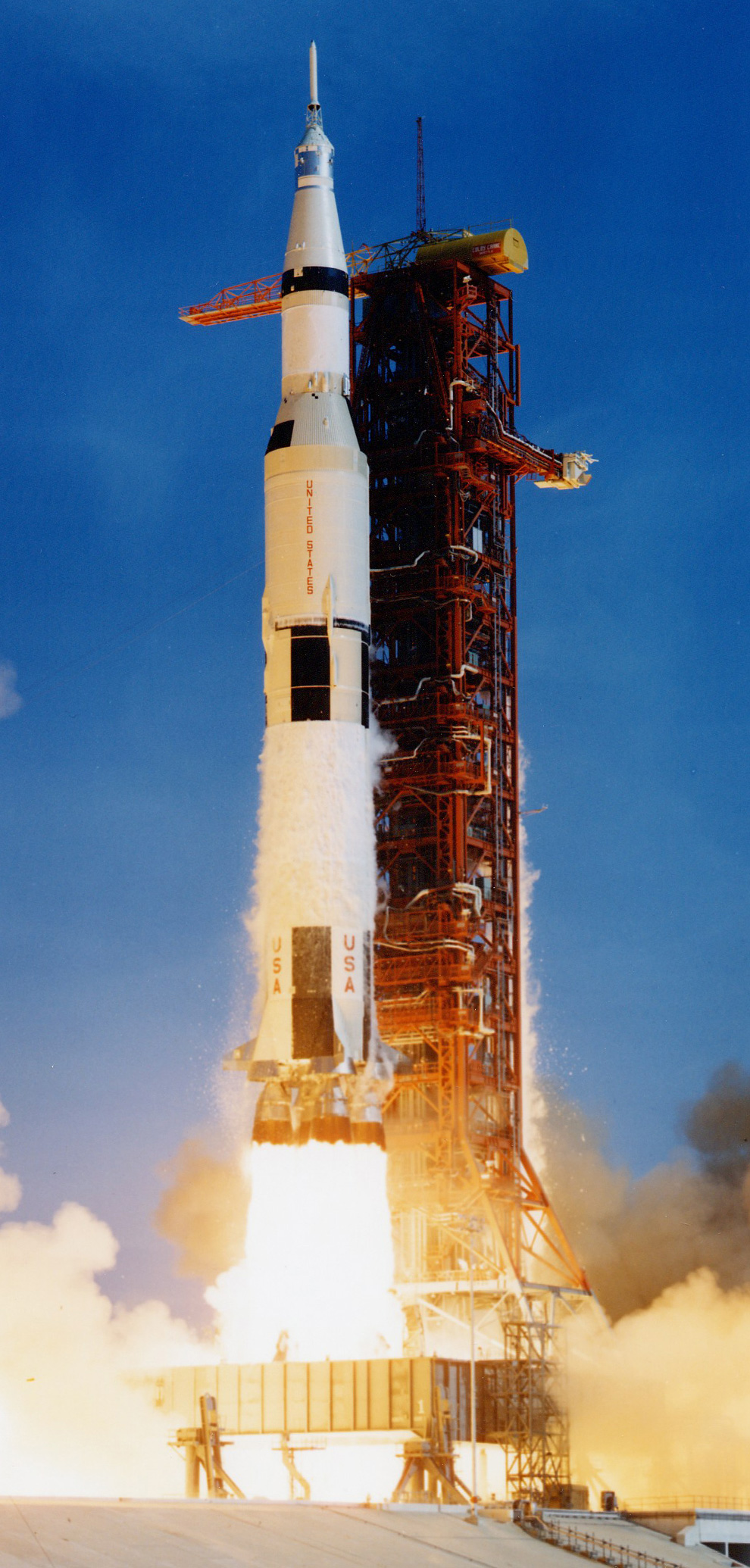

The 40th anniversary of the Apollo 11 moon landing has been the occasion for commemorating a moment of national triumph—by some accounts “the” moment of national triumph in the post-World War II era—with slideshows of “remembrance” at many of the major media outlet websites (e.g., here and here). The photos at these slideshows display a ritualistic pattern of representation that features heroes (both the astronauts themselves, as well as the engineers and technocrats that made it all possible) and images of the earth as if shot from the heavens, a vantage that no ordinary mortal could ever achieve. But more than that, these slideshows are dominated by images that fetishize the technology itself, as with the photo above of the Saturn V rocket that hurled the Apollo 11 astronauts into space.

The photograph is a sublime display of raw and unfettered power. I am typically reluctant to concede the generally all too easy identification of a phallic symbol, but it is pretty hard to avoid the ascription here. The long, thin projectile is literally “blasting” off from the launch pad, powered by nearly 7 million lbs. of fuel (according to the caption). And it is not hard to imagine it as a representation of a nationalist (notice the red, white and blue color scheme) and technological orgasm, a physical expression of force further accentuated by the sheer size of the photograph itself, a 10 X 20 inch reproduction at the website where I encountered it, that far exceeds the dimensions of my 22 inch monitor and requires that I scroll up and down to see the entire image. Indeed, in its own way the photograph as such functions rather like the foldout in a “girlie” magazine that requires the viewer’s active participation in order to take in the somewhat “larger than life” object of desire.

The national media has been complicit with the promotion of NASA and the space program virtually from the beginning, and so I was not really surprised when, in the midst of all of the nostalgia for Apollo 11—and visual remembrances of what we might characterize as vintage techno-porn—I encountered a slideshow at the Sacramento Bee that once again seemed to make a fetish out of our more contemporary space technologies, this time in conjunction with the International Space Station and the recent launch of the Endeavour space shuttle. But what took me by surprise was the slide that ended the show:

The photograph is distinct in a number of important ways that warrant comment. First, of course, is the simple fact that the image features the technology of photography itself rather than the space technology. There is no way to know if those with the cameras are professional photojournalists or pro/am photographers, but in either case the point is clear that the spectacle we are witnessing—whether it is the blast off from a launching pad or a close-up of the space station floating ever so serenely in orbit—is not immediate to our ordinary human perception but rather is refracted through a lens that creates the appearance of closeness or distance, that can expand or diminish the magnitude of the object or event being observed, and so on. So, for example, compare the size and distance of the image of the Endeavour in this photograph with the image of the launch of the Apollo 11 above. What these photographers can see with their eyes and what they will capture with their cameras is not exactly the same thing. The photo is thus something of a reminder of both the fact and effects of technological mediation. And more, it is a reminder that the camera itself is complicit in some important respects in creating the objects of our desire; and this is no less so in observing the idealized presentation of technological wonders themselves than when we are gazing upon the eroticized body.

But there is a second and more subtle—perhaps even more important—point as well. Although the billowing plumes of white smoke indicate a powerful force, it is nevertheless a finite power, as we see that what rises must inevitably fall (pun intended). Indeed, the downward slope of the smoke is at least vaguely reminiscent of some images of the descent of the Challenger space shuttle after its disastrous explosion, and thus perhaps the image is a cautious reminder of the anxiety that seems necessarily to accompany modernity’s gamble—the wager that the long-term dangers of a technologically intensive society will be avoided by continuing progress: every step forward entails some risk, the bigger the step the bigger the risk. Put differently, for all of the positive effects and affects of our landing on the moon in 1969, our remembrances of that event have included virtually no consideration of the costs expended, including the deaths of the Apollo 1 astronauts, or those who flew aboard the Challenger and Columbia space shuttles. And to remember Apollo 11 in this way is to idealize the event that took place on July 16, 1969, to airbrush it, if you will, and in a manner that converts our memory of that day into something of a fetish.

I wonder if we can separate progress and the risks—the triumphs and disasters—of living in a technological society quite so easily. And if we do, we surely must ponder the ultimate costs.

Photo Credits: NASA; John Raux/AP

Thomas Pynchon’s novel, Gravity’s Rainbow (1973?) explores the rocket’s and the overall space program’s grip on our consciousness, views it as a defining spectacle of the age, a spectacle that the US gov’t nurtured and used as a way to keep us all – Americans and those overseas – wowed by technological prowess and American might. GR is aware, too, of the image-making apparatus that worked hand-in-hand with space program. What great theater!

Tom Wolfe’s The Right Stuff looks at this angle, too – the Mercury 7 astronauts are just puppets on a stage.

And most of all, a book called The Final Frontier, by Dale Carter, considers the space program as technical spectacle and as the engine of post-war capitalist expansion and American military muscle. A great book, it uses Gravity’s Rainbow as its springboard.

Finally, GR reminds me: You write “… our remembrances of [the moon shot, etc.] have included virtually no consideration of the costs expended, including the deaths of the Apollo 1 astronauts, or those who flew aboard the Challenger and Columbia space shuttles.” Another great cost hardly ever considered is the deaths of tens of thousands of slave laborers (in terrible underground factories) who helped make the Nazi rocket program succeed, a program whose engineers, scientists, technology, and equipment soon became the foundation of both the American and Soviet space/rocket/ICBM programs.

Anyway, great blog; I just found it via NYTimes mention and look forward to exploring it.

[…] The 40th anniversary of the Apollo 11 moon landing has been the occasion for commemorating a moment of national triumph—by some accounts “the” moment of national triumph in the post-World War II era—with slideshows of “remembrance” at many of the major media outlet websites (e.g., here and here ). The photos at these slideshows display a ritualistic pattern of representation that features heroes (both the astronauts themselves, as well as the engineers and technocrats that made it all possi Originally posted here: Techno-Porn […]

[…] as with tragic injuries and three deaths following equipment failures and explosions. And yet the fetishistic desire never seems to die, a point driven home by the billionaire Richard Branson who noted, […]