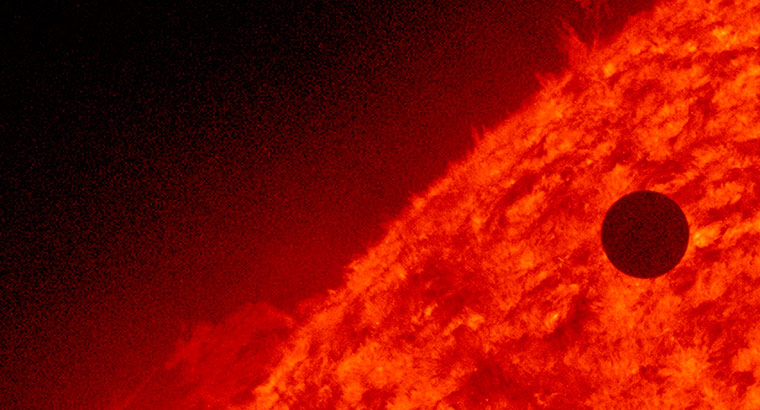

Every summer, it’s the same: forests flare up like kindling, tired emergency crews fall back along the firebreaks, home owners stand guard on their roofs with pitifully thin garden hoses, and the skies are crossed with planes and helicopters cutting through the smoke to drop the equivalent of a teacup of water on the blaze below. Perhaps that’s why I liked this photograph from among the many more dramatic shots taken in the last two weeks.

Although cropped to feature the plane in action, the image still suggests that we are looking at a child’s toy, or at least a movie made for the younger set. Although lacking the spectacular power of Air Force flyovers on July 4th, this nondescript supply plane would be thrilling to anyone still capable of being dazzled by simple technological prowess. And the red fire retardant swooshing behind it bundles together work, warfare, firefighting, fire, drama, and good works alike into a visual emblem of adventure. The West still evokes the majestic, thrilling chords of romantic heroism, even as it burns like the gates of Hell.

The photo doesn’t just play the old tune, however, for it captures as well the miniaturization of human effort when set against the vast backdrop of nature. Westerners get that, although they also forget it from time to time. How can you blame them, for modern civilization is a story of harnessing nature’s power and of living far beyond what the terrain alone would allow. In the past 100 years, the US has damned the rivers, pulled water, oil, and coal from deep in the earth, provided electrical power for everyone, and made the desert bloom. All it takes is a good fire, however, to remind us that human scale is a small thing.

Until, that is, the cool rain finally falls and amnesia returns. I’ve posted on the fires before (here, here, and here), and I suppose I will again. Every summer it’s the same. Except, of course, when it gets worse. As Timothy Egan points out, the combination of global warming and Republican ideology can only lead to disaster. Unrestrained growth while cutting government services (as for fire prevention and fire fighting) gives new meaning to hubris. Need I add that currently these services are underfunded? For example, the small fleet is aging and some planes have had to be grounded, and states and municipalities espousing low taxes once again are turning to the federal government for a bailout rather than burn to the ground.

By trying to live well on the cheap, people are playing with fire in more ways than one. And when a political party or a society develops an excessive appreciation of its own powers, nature is sure to provide a harsh lesson in humility.

Photograph by Kim Raff/The Salt Lake City Tribune.