Writing in Newsweek recently (12/1/07), Peter Plangens reprises an argument that seems to emerge every now and then about the death of this or that medium or art form as it is confronted by newer and different technologies that somehow undermine its “aura.” Walter Benjamin probably made the most famous, recent version of the argument in “The Work of Art in an Age of Mechanical Reproduction,” but let’s not forget that it has a lineage that goes back at least to Plato’s critique of the technology of “writing” and its impact on the importance of the spoken word.

Plangen’s concern is photography, and his claim is that the “explosion” of digital technologies has created a medium that has “lost its soul.” Photography’s “soul,” apparently, is its connection to the “real,” for, as he puts it, “no matter how much darkroom fiddling someone added to a photograph, the picture was, at its core, a record of something real that occurred in front of the camera.” That was the original allure of photography, of course, but it was more a hope (or a faith) than an objective reality. And it didn’t take take avant garde photographers like Cindy Sherman to show us otherwise. Indeed, from the beginning the history of photography is replete with a wide range of examples that make the point, not least the work of prominent and important documentary photographers like Alexander Gardner during the Civil War (with his sharpshooter photograph) or Arthur Rothstein during the Great Depression (with his skull photograph). And these are not lone instances.

That said, while the advance of digital technologies has altered the way in which we think about and use photographs—and very clearly has reinforced a postmodern cynicism about realist representation that seems to worry Plantgen—it has also arguably invigorated photography as a cultural practice, enabling something of a rebirth out of the ashes of modernism. That rebirth includes not only a much wider democratization of the use of photography—witness the millions of digital cameras in everyday usage, many contained in cell phones that are carried about as a matter of course like one’s wallet or purse—but also in its capacity (in the words of Patrick Maynard) to “enhance and filter human power” in a broader spectrum of visual possibilities.As an example, consider the photograph above that was recently published in the on-line version of the Washington Post. It is a stand alone photograph of 55 year old Angel Lopez, the patriarch in a family of five who were unable to find refuge in a Bronx city shelter and were forced to spend the night on the streets.

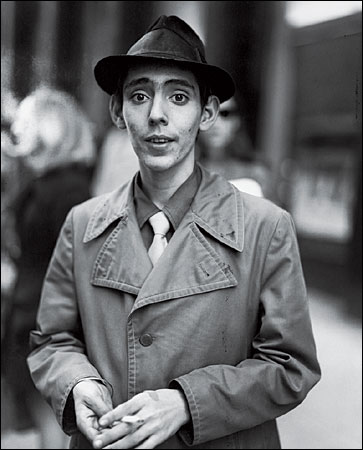

It is a compelling and affective photograph, all the more so given that there is no story that accompanies it other than the caption which identifies Angel and his family members as “A Family in the Streets.” Shot in a middle space between the camera and a long street that invokes the conventions of classical perspective, distance is privileged as an aesthetic, bringing us closer to the homeless than we might imagine that we need – and perhaps would prefer – to be. Angel is in the very center of the image, his eyes making contact with the camera in a manner that demands recognition and a response. But what could his demand be? Clean and neatly dressed, he doesn’t seem to be the stereotypical homeless person or skid-row bum, and in any case the crutches make it clear that he has a hard time helping himself and thus stands in need of our care. In its own way the photograph is vaguely reminiscent of Dorothea Lange’s “Migrant Mother” with its projection of social responsibility for others. But, of course, it is hard to know.

Now click on the picture. A quick time movie should open in a new screen. Give it a moment to load. What we have here is a 360º panorama of the scene. Now we see not just Angel, but all of the members of his family. We are now pulled into the scene more directly as we see (and hear) Angel and his family briefly reflect upon their plight. While they all appear to be looking at the camera in their turn, they also seem to be interacting with one another as well, thus suturing the viewer into the scene in a manner that dictates a more complex social register. This last is underscored by the interactivity of the medium itself as the viewer can zoom in and out of the scene by manipulating the “+” and “-“ buttons on the screen.And with each click, of course, the social and political dynamic changes, pulling us in or pushing us out. But even as we zoom out and distance ourselves from the scene we are forced to take account of the full panorama.

No more “real“ than the earlier photograph, the panorama nonetheless invites and invokes a different affect, a different social and political interaction with the image; and I would argue it is at least potentially a more progressive kind of interaction because it doesn’t allow for a simple passive turning of the page. The image is still controlled in some measure by the camera and the photographer – the frame remains as a constraint on what we can see and know – but as a technology the photograph now filters the relationships between Angel and his family, the street, and the absent state in a somewhat fuller and more engaging fashion. Whether this increases or decreases our sense of compassion or willingness to work to make sure that such situations don’t persist is hard to say, but it would be interesting to consider how such usage would have altered the affect of 1930s FSA photography or Edward Steichen’s 1950s Family of Man exhibit (not to mention, say, the scene of a bombing). But however we evaluate the particular affect of this panorama, the larger point here is that the “soul” of the photograph is not contained by the particular technology of mediation per se, but is rather a function of how such images are received and used (or abused).

As long as we actively make and use photographs – engaging them and talking about them, drawing from them as markers of our sociality, as well as questioning and challenging their politics and affect – they are not likely to lose their soul as a simple function of the particular technologies through which they are enacted, be it framed in terms of the the “magic“ of the nineteenth-century daguerreotype or what Plangens blithely refers to as the “fairy tale” fantasy of Photoshop.

Photo Credit: Travis Fox, Washington Post; and with credit to Patrick Maynard, The Engine of Visualization: Thinking Through Photography (Cornell UP, 1997).

Update: For another critique of Plangens at American Photo go here.

6 Comments