The news of the past week has included disaster coverage of the earthquake in Peru. A level 8 quake, it was a bad, killing at least 500 people and rendering thousands homeless. This photo is typical of the coverage:

We see survivors contending with shattered housing. Whether to undertake extensive repairs or rebuild from scratch obviously is a real question. Equally evident is the relative calm. People are dealing the the aftermath, but the quake is over. A cinder block will fall here and there and the area will remain somewhat dangerous during the clean-up, but people can get to work and help one another like the two guys in the picture, as everything is settling into place.

The news coverage already reflects (models) this thoroughly pragmatic state of affairs. We hear of governments, international aid organizations, churches, and other volunteers swinging into action. Public discussion begins about the effectiveness (or lack thereof) of early warning systems, architectural designs, first responders, and other matters of public safety and infrastructure administration. The press also provides stories and images of solidarity: people praying together, impromptu vigils, neighbors assisting neighbors. These are good stories, even if we all know the drill. The stories have consequences: many readers will open their pockets, local governments will review disaster response plans, social networks will expand, and for a while lesser quake victims will receive news coverage and the benefits thereof that they would otherwise have missed.

One can still find much to fault, of course, but the whole business is at bottom a testament to the public value of news coverage and the organizational effectiveness that it nurtures. It also is an example of the power of framing. Look at this photograph:

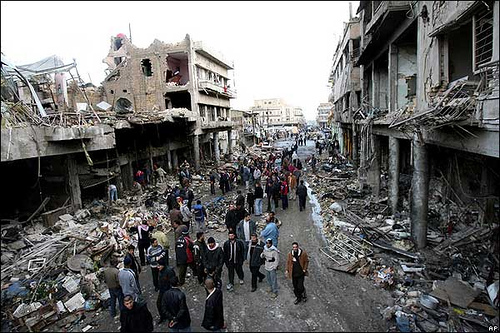

This, too, could be a photo of the aftermath of an earthquake. Instead, it’s a Baghdad marketplace following a bombing. This one killed 170 and injured over 300, according to the first count. The week of the Peruvian earthquake saw blasts that killed 500+ Yazidis in two villages year the Syrian border. Since the invasion of March 19, 2003, at least 300 Iraqis have been killed by warfare every week, week after week, for a total thus far of at least 70,000. Think of it: an earthquake a week, every week for four years.

I can’t help but wonder what might change were enough people to label the situation in Iraq a disaster. Of course, it is a war–in fact, several wars all mixed up together. But here the war frame can only lead to more war. And for all the expressions of sympathy for those being destroyed, the response to Iraq at all levels has virtually none of the pragmatism and cooperation characterizing disaster relief. This difference in attitude is reflected in the two photographs above: in one, the viewer is at street level, close to the scene, postitioned as if to lend a hand; in the other, we are looking down as if “seeing like a state,” emotionally distanced from a mass of people being channeled through the “collateral damage” of history. One frame pulls us into the picture, and the other provides the secure perspective of geopolitical observation.

One can’t wish away the problems in Iraq by changing a label any more than one can fix it by waving a magic wand. And yet it is looking unlikely that the US will extricate itself any time soon, while our military presence there will continue to be a major cause of the carnage. This is in fact a disaster in more ways than one, and perhaps it is time to say so and, more important, to act as if it were so.

Photographs by AFP/BBC and Khalid Mohammed/Associated Press.

Regarding the first picture, you write:

“We see survivors contending with shattered housing. Whether to undertake extensive repairs or rebuild from scratch obviously is a real question. Equally evident is the relative calm. People are dealing the the aftermath, but the quake is over.”

Odd that my first thought was “Maybe they are looters?” Maybe that says something about our assumptions?

The same applies to the photograph of the Baghdad marketplace.

“One can’t wish away the problems in Iraq by changing a label any more than one can fix it by waving a magic wand. And yet it is looking unlikely that the US will extricate itself any time soon, while our military presence there will continue to be a major cause of the carnage. This is in fact a disaster in more ways than one, and perhaps it is time to say so and, more important, to act as if it were so.”

Assumptions again. The quake is over in that photograph too, but we know there will be more quakes — because they are driven by flawed human beings, not tectonic plates. Maybe it will stop being a “disaster” when the US military leaves, not because the killing will stop (indeed, it will rise — I know since I’ve been there and seen what happens when the US leaves an area) but because the cameras will go away. Prime evidence? Look at Somalia.

It’s Very Interesting Article And I have Enjoyed Reading it , I’m From Iraq And I can tell you that that 90% from this info is true . The Station is hard in Iraq now and as you know we had election not long ago and we all wish everything will be find soon .

Thank you for this article I am happy to part with you, I think that everything will change, and certainly I see things from the other side,I’m from Iraq … .. only for welcome …