The following two images each merit their own post, but I also want to point out how they suggest a larger pattern. First, there is this shot from a morgue in Pakistan following the attack on Benazir Bhutto’s arrival in Karachi.

I noticed the photograph because it was another instance of photographing only feet rather than the upper body or entire body. Readers of this blog may have noticed that “boots and hands” is one of our archival categories, as John and I are interested in why these truncated images appear frequently in mainstream photojournalism.

The feet featured here are bare, brown, worn (look at the back of the heel), and charred. They may have belonged to a middle class accountant, but it is difficult not to see them as peasant feet. The burns look like dirt, and feet have symbolized peasantry in the discourse of the body politic from antiquity to today.

Above all, these feet are dead. The awkward angle suggests a broken body, and the caption cues us to see the stiffness of rigor mortis. Most important, life itself seems to have been thrown away as the blood spilled on the floor forms a hopelessly large, ugly stain on the tile floor. It is as if the body had been drained prior to being preserved, and the feet do look like a specimen. More to the point, the photograph makes this stiff, dismembered, emptied, anonymous body into a specimen, as if it were something awaiting taxonomic classification before being filed away in a natural history museum.

It is easy to claim that the photographic gaze objectifies human being, and I usually avoid that critique. Surely it is not the camera but rather a bomb that turned this living person into a thing. Indeed, perhaps the photograph is doing something else: not objectifying but creating a visual allusion to the Holocaust, that is, to the images taken there of bodies stacked like cordwood. If so, that again points to those using weapons, not journalists using cameras.

Fair enough, but let’s look at the second photograph.

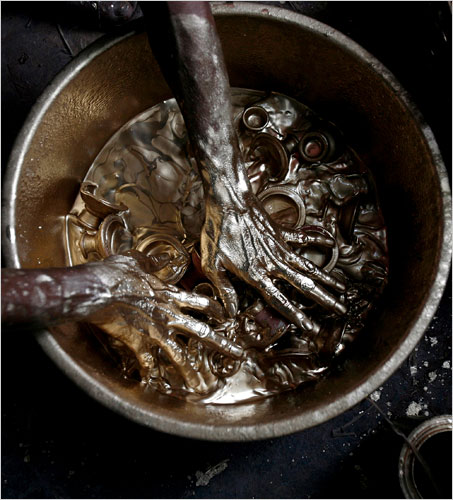

This is a beautiful image. Edward Weston once remarked that color photography should be taken seriously when the photographer could see “colour as form” rather than a decorative addition to the black and white image. (There’s more to color than that, of course.) The artistic intensity of this image comes directly from the formal power of its dense richness and subtle variations of brown and bronze, all captured through the silver light that seems to have been painted by a Renaissance master. Likewise, the circle of the bowl is repeated in miniature by the circles in the solution and the half-circle in the lower right of the frame, and so the formal completeness of the circle is fused by color and light with the brachiated pattern of the arms and hands, which converge and then branch out again.

And yet, something is missing. The body, for example. Once again, we have a dismembered, anonymous peasant, in this case a man painting “earthen lamps at his workshop for the Hindu festival of Diwali.” The “painting” is crude, simply immersing objects in the paint, and the lamps are “earthen,” the sort of thing that comes from a workshop rather than a factory. Even that humanizes, however, for the image itself gives us something beautiful but also alien, almost arachnidal as those hands spider across the surface, breathing paint and light.

What is most interesting to me is how, again, life is being separated from the body. In this case, the inanimate nature of bowl and paint seem to have already recast his hands and are moving up his arms. It’s as if his primitive workshop is the early form of some later fusion of human and nonhuman processes in a Blade Runner shanty town. The lamps are being changed by his labor, but he is being changed by the metallic solution coating his hands. As it is, the paint may kill him, but the image suggests a post-human worker who won’t have that problem, as life already will have been altered to become part of a process of production.

Each photograph is a distinctive portrait of a specific event, yet together they suggest a third thing: the idea that the peasant is disposable because not really alive. After all, there aren’t supposed to be peasants in a modern world. The good news is that other, more Romantic concerns are well off the table: You see no noble savage here. But you also see common people as either specimens of natural history, or as artistic premonitions of the post-human. In neither case are they alive—in history, in the present, or in the political imagination.

Photographs by Paule Bronstein/Getty Images and Parth Senya/Reuters. Weston’s remark is cited in Geoff Dyer, The Ongoing Moment, pp. 190-191.

I think a different audience would see a very different thing in th picture of the hands–not cyborgs. I haven’t studied much Hinduism, but the Sanskrit word for “gold” is “suvarna,” which means good-color, where varna is also the word for caste. The Buddha, for example, is made of gold in some versions. I see a ritual act whose divinity transforms the skinny, dark brown worker’s hands of the painter into something divine where he touches these objects. I don’t know about the racism of modern India very much–all my reading is in Sanskrit. I do know that when we paint our skins gold it means a very different thing from when we paint them silver.

Yes, it is likely to have different meaning for those within the culture depicted. I try to only make claims about how the image might work within US public culture, where there still will be variant meanings as viewers bring different standpoints, experiences, and knowledge to bear. The interpretation of each image also is changed–and perhaps distorted–by putting it in conjunction with the other. I have some doubt about whether I should have paired them at all. Keeping them separate gives each more room and allows more to be said about how each is distinctive. For example, after I had posted, it occurred to me that the feet in the first photograph could allude to crucifixion. I probably missed that connection because it didn’t fit neatly into the comparison.

I think plenty of people in US public culture would see two different ways to become divine, then. On the other hand, that’s very much a dehumanizing process anyhow.

there is lots of blood.

[…] (even if it is there to be seen). And I could have said more–in fact, I have said more in a post on a similar image (see the second photo in the post) in October 2007. As today, that image was taken during […]