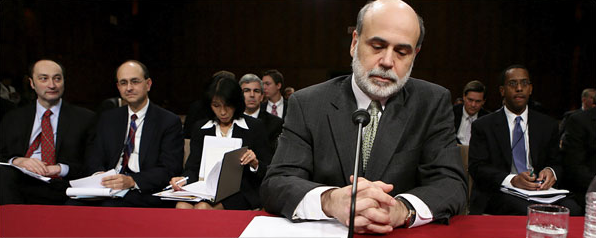

Last week I posted about this photograph of Reserve Board Chairman Bernanke preparing to speak before a congressional committee on economics, contrasting the ritualistic, faux-piety of the scene with the photographic representation of the gluttonous impiety of Marshall Whittey, a sales manager for a floor and tile company in Reno, Nevada who was feeling the “pinch” of the equity credit crisis that left him “eating in” more often.

I suggested that the juxtaposition of images, published as part of separate articles in the NYT on the same day, invited a civic attitude that located the problem of the economy in the psychology of private life—individuals making bad economic decisions—rather than in any inherent systemic problems with the so-called “free market.” One reader wondered if the affect of the Bernanke picture would change if we were to juxtapose it with a more tragic and typical representation of a foreclosure or eviction; another reader pondered whether it was even possible to represent systemic social problems visually without reducing them to individuals in a manner that might tend to discourage collective action. These are both excellent questions that deserve a second look.

Several days following the Bernanke’s report to Congress the NYT published this photograph as the lead-off to an article in its Week in Review:

The caption reads “EX HOMEOWNER Esta Alchino of Orlando, Fla., was late paying her mortgage and lost her house.” Both this photograph and the one of Whittey point to individuals caught in the equity crisis, of course, but in this case the photograph is framed by the title of the article, “What’s Behind the Race Gap?” The difference is pointed, for the earlier article focuses on how an acquistive individual, is being “pinched” by the economy and his risky economic decisions; here our attention is directed to Esta Alchino as a representative of racial difference, and thus, presumably, a systemic state or condition, i.e., racial discrimination.

The tension between the two photographs is particularly conspicuous. He sits in his home amongst his prized possessions, she stands in front of (or is it behind?) what used to be her home with nothing but the clothes on her back. Both look out of the frame to the viewer’s left, what we conventionally understand to be the past, but what they purport to see behind them is somewhat different as he exudes a devil may care attitude, a gambler who made poor choices but will be back to play again as soon as he has recovers his stake, as is the promise of the American dream; she wipes tears away in contemplation of a profound loss as she looks back on a national history of racism in which the “dream” seems always out of reach for our dark skinned citizens. The key to the two photographs might well be how the citizens/actors are located within their respective scenes. His home is large, lavishly adorned, and full of light with the promise of more by simply opening the shades behind him—a simple personal choice; her former home is small and dilapidated, lacking any adornment whatsoever, and drab by almost any standard, even as it sits in the full light of day. He is the lord of his manor, accompanied by his dogs; she is completely isolated and disconnected, visually homeless and without any sort of shelter, either physical or symbolic. She is literally alone in the world.

The question is, how might we understand this later photograph as an indication of a systemic problem? What makes Alchino more an illustration of racial discrimination than simply an ineffective liberal economic actor? This is no easy question, but part of an answer can be found in considering how Alchino is framed as something like an “individuated aggregate,” an individual posed to stand in for an entire class or race of people. Here that is marked in part by the fact that she is never once mentioned in the accompanying article that features two neighborhoods in Detroit, a city that is a fair distance from Orlando. We know nothing about her beyond the fact of her race and that she could not make her mortgage payment. We are never even told why she could not make the payment, though we are told that on par high-cost subprime mortgages tend to be concentrated in “largely black and Hispanic neighborhoods.” As such, she stands in as a victim of circumstance, and as the article underscores, the circumstance is a potent and often ignored systemic racism.

The additional question is how we might understand the portrait of Bernanke differently in comparison to the image of Alchino, who is arguably more representative of those harmed by the equity crisis than Whittey. Here, of course, Bernanke’s countenance now changes some, as his prayerful pose seems sorrowful and contrite—worried less about the difficulties of his own job, than about the conditions of people like Alchino. But of course, this comparison is problematic as well, for if we go back to the words he spoke that day, there is nothing that indicates a concern for systemic problems of any kind, either rooted in economic policy or more deeply in the kind of implicit de facto racial profiling that seems to be pronounced within the mortgage industry. What the different comparison of the images does speak to is the need for more sustained consideration of how any particular photograph operates within the visual economies in which it appears.

Photo Credits: Doug Mills/New York Times; Joe Raedle/Agence France-Presse/Getty Images

![]()

“What the different comparison of the images does speak to is the need for more sustained consideration of how any particular photograph operates within the visual economies in which it appears.”

Here, here!

So then the next question is how to inspire this sustained consideration… Can such a consciousness be taught or even learned? By what means? Ought it be instituted into compulsory education?

I’m just beginning to dig deeper into these questions so any thoughts shared are much appreciated…

Wow. I’m glad to see that you brought this one back around again.

The second foreclosure image surely does change Bernanke’s tone and feel in the original image.

All of these images focus on individuals, and we set up relationships between the three. On the one hand, they are only individuals, real people with histories that we don’t know. On the other hand, they are symbols of broader perceptions and stereotypes. These interpretations are much less stable because each viewer will contribute their own content which will take it in different directions.

For instance, Bernanke is an authority figure–clean, tidy, well groomed, properly humble in that senatorial “I’m here to take my lumps and hopefully not suffer in my career” sort of way. It is a PR move that politicians must learn to perform if they are going to survive a crisis. One person might admire that sort of forced piety as a well played political move while another might despise it for its lack of substantive ability to actually address the damaged caused by the sub prime fallout.

In the case of Whittey, there is a kind of kitschy baroque quality to the image, with the expensive toys and the lapdogs but little evidence of actual taste in his surroundings. He comes across a symbol of the neuveau riche, a class frequently associated with surface trimmings and little substance. He also comes across as worried about very little, happy go lucky and unfazed by the collapsing real estate market. Again, this image can read both ways. Some may find this to envied while others think it lacking in substance.

In the third image, Alchino comes in to represent the estimated 500,000 foreclosures that have already happened through the sub prime fallout. She is poor, black and female, all variables that make the image preloaded to go in any number of directions. One viewer might feel compassion for her condition and wish for government relief for her crisis, while another would say she should never have signed on for such a loan if she couldn’t handle the payments.

The problem in each of these images is that they are too loaded with emotional and social content to direct the collective into any kind of meaningful action. A social conservative is just as likely to have their view reinforced here as a liberal progressive. Thus the images are equally likely to direct viewers in different directions and so the aggregate effect is inaction because no clear collective action exists.

Ofelia: That statement does smack of academese, which we try to avoid, but then again, we are what we are. And, of course, your questions are the big ones, central to the rhetorical tradition and rhetorical pedagogy since antiquity. How does one create such a consciousness? I’ve always been inclined to looking at lots and lots of examples of the thing involved and imagining the range of ways in which they might be “reasonably” interpreted and used … how might we imagine them being used in context. How does one teach it? I think you put people in the way of the problem and tease them into engaging it, offering tools for doing so, i.e., analytical vocabularies, historical antecedents, comparisons and contexts, and the like. As to “compulsory education” — the word “compulsory” always makes me start a bit. But the idea of promoting something like rhetorical visual literacy — another ungainly and academic term, to be sure — isn’t a bad thing. And, in some measure, that is what we imagine NCN as doing.

a.m — Great (really great!) read of the images and the problem that their accumulative effect poses. I especially missed the nouveau riche quality of the Whittey image, and its baroque qualities. That is of course essential to distinguishing Whittey and those he represents (who are the problem … right) from those who “know better” how to handle their money/desire. I’m also struck by your comment on the overdetermination of emotional/social content. I wonder if it is that per se, or if it is that there is no “eloquent” articulation of the content. I know the word “eloquent” is vague, but I’m thinking here of the what Hariman and I call the “iconic photos” (like Migrant Mother, Times Square Kiss, Accidental Napalm, etc.) They ALL are overloaded with the same emotional and social content BUT these various registers of affect are coordinated in ways that tend to invite and animate collective action (maybe). Of course meaning is never truly stable, and so they too are open to interpretation and usage across the political spectrum, BUT usually that work relies on negotiating the tensions created and sutured by the eloquence of the image — whether because it is creative and elegant or borrows effectively from prior cultural forms or …

There is also the question here as to whether photojournalism is constrained to undermine collective action somehow, at least to the extent that it features individuals. There are counter examples, as with the iconic photos, but they are few. This is something we need to think much more about. But I am reminded of Lance Bennett’s work in which he argues that journalism in general operates with a “status quo bias,” by which he means that it tends to reinforce the way things are … neither guided by left or right per se (not that those are the only choices), it works under the assumption that the system will care for itself per se.

John,

I think I understand what you are getting at in your exploration of the “iconic” images. A the root, the question in making images like that is how to get to that “eloquent” articulation. It is what is rewarded in the marketplace, for sure. As a working photographer, it is always clear that the audience brings a lot to that relationship with the image.

As photojournalists, we go into real situations with real people and we make pictures of them. Once removed, the pictures function as tableaus in the public square. There is a performative quality to their operations. In the case of the three iconic images you mention, it seems to me that they all articulate a national mood or consensus that was in existence coincidentally to the making of the image. Lange’s Migrant Mother performs on a national stage where the ravages of the depression had left nearly everyone in the country in a agreement that some political solution was required. The Times Square Kiss comes at the end of WWII, again a time of national unity in opinion. It would be hard to find an American that didn’t share the sense of joy and relief and passion in that photo. And again, in the Accidental Napalm image, a foreign, unpopular, increasingly unjustifiable war is revealed to be also cruel and inhumane (how the idea that there is a humane and civil war got into the public mind is a good topic for another discussion.) But in all, the photographs perform in or even galvanize a collective experience that is unified. I’m not sure how much the photographs do to create that unity, though. Some for sure, but the audience has to be there too for it to happen. Perhaps that eloquence, as you describe it, is only possible in moments where collective consensus exists.

In the case of the social, racial, political, and economic issues brought up in these three images above, no consensus exists at all, and the collective is already divergent in its understanding and interpretation of the issues. The photographs operate emotionally in much the same way the the iconic images you describe do, but little collective action is possible. In the case of these complex and ambiguous issues, some emotional restraint might be a better approach in editing the images, although I can’t say for sure. We could compare, say the New York Times and The Economist in this way. The Times images certainly turn up the heart strings while The Economist images are by comparison boring, to be blunt. Both achieve a very different reader experience, and this is not by accident. It is by careful editing.

JOHN – Indeed we are what we are… And, I don’t mind a bit of academe so long as the effort to put that thinking to practical (and, ideally, positive) use is there. I’m drawn to NCN for this very reason.

A.M. – You mention that the audience brings a lot to the image… and talk about the coincidence of the image’s performance matching a national mood or political consensus…

I hold a slightly divergent perspective of these circumstances ; one in which the photographs function as both a rallying point for those already in a particular mood about some collective experience or mass event as well as a catalyst for emotional/political action/responses to the issue at hand. Generally, the context of any image’s performance and presentation will direct, if not dictate, our reading of the circumstance from which the image was made. Especially weighty in this process of meaning-making is the perspective from which the viewer comes – emotionally, politically, (in this case, even financially)…

A good example is Christopher Morris’ book My America. I happen to know Chris and he once told me the story of that book… Much as he loves the work, the life those images have led is a bit maddening. His initial thought was to publish the work with a scathing essay. Covering the White House for TIME precluded that and he didn’t want to wait until after Bush to put it out there.

When the book was published, it met acclaim from both sides of the aisle. The political conservatives who are the subjects of the photographs loved it as a portrait; they find it to be an interesting representation of their time and often Chris has walked into an office and spied a copy of it on the coffee table. Others view the photographs as a revelation or visualization of the ‘ask no questions, i’ll tell you no lies’ mentality that has created/caused/contributed to the current crises at home, in Iraq, and so on. They buy the book and put it on their coffee tables to say, “Look. See what’s wrong with these people.”

In this case, the eloquence exists for both parties though the meaning given the images themselves are oppositional and contradictory. Without Chris’ words to tell us what he wants these images to mean to us, we are left to allow them to mean what we want.

Those of us who know that the economic woes of the housing market are devastating the lives of many who are already struggling and impoverished will chide the newsmakers for such lackluster, and maybe even demeaning reporting. Why are we looking at Whitey who is suffering nothing but the loss of a few catered meals? Shouldn’t we be seeing Alchino always? Should the images be edited to achieve a maximum emotional response? – keeping in mind that a positive social reaction, not inurement or attribution to systemic unchangeable circumstances, is the ideal goal…

Better that Bernanke’s false piety be presented in relation to suffering rather than discomfort, leaving less space to conclude that what has transpired is merely an unfortunate inconvenience that shall soon pass. This would at least be a beginning or a setting of the stage for a mentality inclusive of the thought that collective action is not only needed, but possible.

Ofelia: Very (very) well put. And welcome to the NCN community …