Recently the Chicago Tribune ran a special report on one of the lesser known consequences of war: an increase in mental illness among civilians. The story is set in Somalia and includes a slide show of scenes from the only mental health clinic in Mogadishu. Some of the patients will be dangerous to themselves or others, and so the problem arises of how to restrain them. In the West, this is done with drugs, locked wards, and other disciplinary technologies. In Somalia, the means are simple, though effective:

This young man is chained to a tree. Viewers in the US shouldn’t get too judgmental, as here he could be “free” but homeless, sleeping in the ground, and less likely to be fed regularly. Better resources are needed in Somalia and in the US. My question is, what can photojournalists do to motivate public action on behalf of the mentally ill wherever they are? The press can be damned either way: one always will be faulted if not documenting a social problem, while visual documentation is subject to charges of creating an atrocity aesthetic and compassion fatigue. How, then, should we assess this image?

We can begin by asking how it seems unique, and then how it might nonetheless iterate prior images and assumptions. The photograph is distinctive because of how it places the young man prostrate, legs splayed and body core exposed, and because the girl huddled behind him suggests an unending series of damaged souls, and because the viewer towers above the scene. Indeed, the angle joins the viewer with the trunk of the tree: strong but immobile, anchoring a system of benign restraint but not responsible for the fetters. This is not a position of action.

One reason the photo above caught my eye is that I’d seen it before.

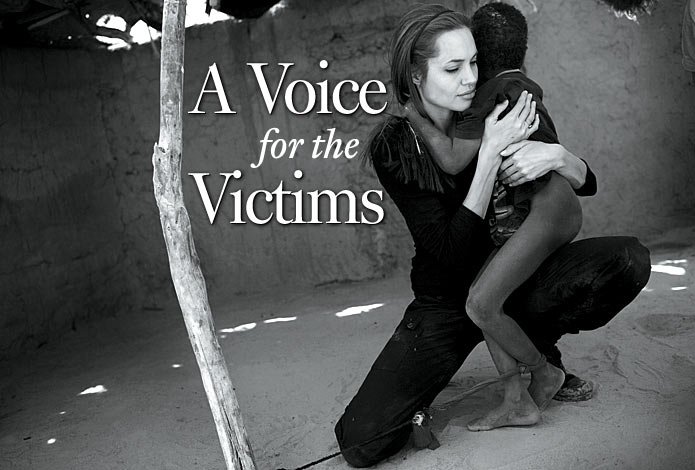

This is the signature shot from the March 19, 2007 edition of Newsweek. (The image was brought to my attention last spring by Beth Iams, who wrote a fine paper on the magazine’s photo essay for my graduate seminar on visual rhetoric.) The story, “Star Power,” chronicled Angelina Jolie’s attempt to focus attention on the suffering in Darfur. Jolie states that “‘If I can draw you in because I am familiar, that’s great because I know that at the end you’re not looking at me, you’re looking at them.'”

Of course, the image is all about Angelina, and there are very few correspondences with the first photograph. I think the few that are there are important, however. The boy is restrained for the same reason in each, and perhaps the tether is becoming a visual convention. (There are other examples of this tether and other forms of shackling by the two photographers.) If so, we might consider how it not only depicts limited means but also implies more fundamental deficiencies. As long as the tether remains identified exclusively with mental illness, poverty, and Africa, it ties understanding to a host of assumptions about premodern medicine and social organization. Never mind that the restraints shown above are age-appropriate and keep the patient within the daily round of community life. Such considerations fall outside the modern disciplinary matrix.

Thee might be a second set of implications. We see not only restraint but also a black body, male, barelegged, tethered to a pole. I can’t help but wonder whether these images allude to lynching photos: whether hanging barelegged from a tree, as in the famous photograph from Marion, Indiana, or chained to one in order to be blow-torched, as in Without Sanctuary. Whatever the source, the association is horrific, and completely mistaken. It could be there, however, in the hope that the public would be motivated to act if they intuitively sensed that they were witnessing a similar descent into brutality.

If there is a chain of visual allusions binding African victims of war to American victims of terror, it surely is unconscious. One should ask whether it might also be influential, and to what end. Are the photos merely imitative of those before them, or are they artistic attempts to mark yet another breakdown in humane social order? Are we becoming complicit in normalizing violence, or is some potential for public action being suggested? Are they hypocritical reconstructions of a tragedy on familiar terms, which certainly is part of the Angelina Jolie story, or do they reflect some peculiar progress regarding public understanding of the suffering of others?

You tell me.

Photographs by Kuni Takahashi/Chicago Tribune and Per-Anders Pettersson/Getty Images. Newsweek gave a documentary tone to the second image by reproducing it in black and white; you can see it in color here. Note also the recently published Beautiful Suffering: Photography and the Traffic in Pain. Thanks again to Beth Iams, who can be contacted at elizabethiams@yahoo.com.

Yes, I think they’re all those things, except for the last half of your last sentence. Certainly I think the chain of visual illusions is more obvious than unconscious.

I listened to a peculiar set of interviews about so called ‘waterboarding’ (near-drowning to force confessions). Its defender quite categorically emphasised that because various military practise it on themselves in training, it cannot therefore be torture.

Although you are quite right to draw the parallels and similarities between the different forms of restraint, that all seem to me much like torture. Whether or not someone has mental health problems should not mean they require restraint, however this is achieved.

Not sure where I’m going with this, but there is a point here somewhere, and a powerful one. I probably need to read that book. Thanks.

The book to read is Discipline and Punish by Michel Foucault.

I commend you for this excellent piece. For far too long have Americans and now the rest of the world been fed images of these kinds without truly appreciating the human condition. The saying “A picture is worth a thousand words” is a testiment to the power of images and those images carry power because of how they are inherently connected to our socialization process.

A well known magazine recently published a cover image of LeBron James with his arm around an actress, dressed in his NBA uniform, his face snarling, palming a basket ball while she hung to his side, white flowing silk gown, long blonde hair and a demure smile. I’m not sure what was on their minds when they were asked to pose like that but compare it side by side to the original movie poster of King Kong that was released more than 40 years ago and it’s almost and exact match. Coincidence? Hardly!

Images carry a context with them and for those informed and aware, they can speak more than a thousand words. It’s important for the photographer to decide if those words are positve and inspirational or damaging and destrcutive.

Thank you!