Yesterday the news in the art world included a New York Times story on “A Big Gift for the Met: The Arbus Archives.” The paper reproduced two of her photographs, the deeply affective “Russian Midget Friends in a Living Room on 100th Street, N.Y.C.,” and the more often reproduced “Woman with a Veil on Fifth Avenue, N.Y.C.” (The later is doubly jarring today, when “veil” is taken to refer to something quite different than an affluent white woman on Fifth Avenue.)

If you follow a link provided by the Times, you can see several photos that were revealed at a major retrospective of a few years ago. They are pure Arbus, and all the more stunning for that. This is art, and I won’t presume to add to what has been said to celebrate her achievement. It is enough to look:

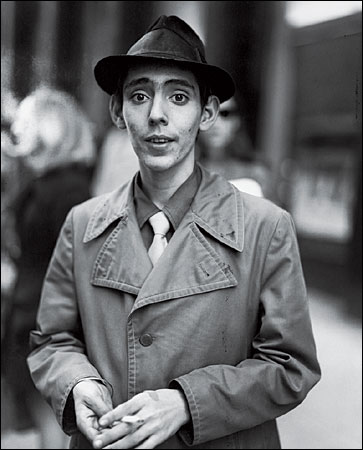

He is no freak and the more exposed for that. Although composed for and confidently presenting himself to the camera, we see a profound vulnerability. Dressed for going out in public or to the office, he seems almost naked. Covered, even layered, he seems thin, at best a thinking reed. And can anything that gentle not be mowed down? It seems that the wind could cut through him like a bullet, and won’t the many snubs, rejections, and disappointments to come do the same?

That may be too morbid, however, an homage more to the Arbus aura than to the art itself. Perhaps he already is well armored. Look at the formal perfection that she captures: the arced lines of his eyelids are paralleled by his eyebrows and the brim, band, and top of his hat. The long oval of the face is mirrored by the ears, their protuberance now an aesthetic virtue. Likewise, the arcs of the lower lids, lower lip, and chin are mirrored by the V-lines of the collar, coat, and his arms. Eyes, mouth, hands; ears, lapels, hands–the incredible candor and goodness in his direct gaze at the camera is buttressed by these symmetries of composure. What should be a confrontational stance is instead a moment of pure openness. He, not just the photograph, is a work of art.

Except for the cigarette. That’s the punctum for me. The term was coined by Roland Barthes to describe the part of an image that punctuates or punctures interpretation to create a more intense or troubling emotional effect. The cigarette puts this young man back into time. He is living in a particular time and place and social world, and time is passing as surely as that cigarette is going up in smoke. Thus, the photograph brings him, and us, back to all the desires and vicissitudes and erosion of real life. He doesn’t have it all together; he’s imitating a movie star. He isn’t composed and armored and capable; he’s playing a part for which he is ill cast and cheaply costumed. He’s not open to a life of possibility; he’s already caught in an epidemic. The wind won’t blow through him, but he could end up thinner yet as cancer wastes him to the end. He’s really one of us.

Young Man in a Trench Coat, N.Y.C., 1971, by Diane Arbus/The New York Times, “Unveiled (September 14, 2003),” and Diane Arbus: Revelations.

Discussion