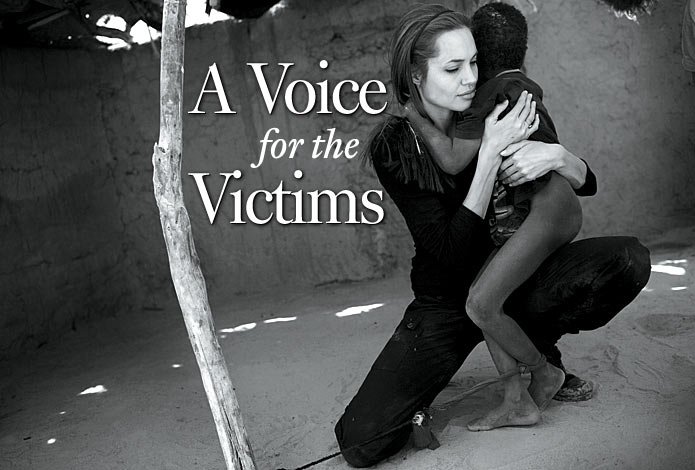

Two soldiers walking past a burnt out vehicle on a city street. It is an altogether ordinary photograph of what has become an altogether ordinary event in the Persian Gulf region, if not the Middle East more generally. A somewhat long caption tells the story in a passive, matter of fact voice, “U.S. soldiers pass by a damaged armored vehicle following a suicide attack in Kabul, Afghanistan on Tuesday, Nov. 27, 2007. A suicide bomber blew himself up next to a convoy of armored vehicles used by foreigners in Kabul, in a huge explosion Tuesday that killed at least two civilians and left the wall of a nearby house in ruins, witnesses and officials said.” We have seen similar photographs hundreds of times in recent years and its only real distinction would appear to be its almost pure banality.

Appearances, however, can be deceiving. The photograph was published on the Washington Post website on Wednesday, Nov. 28th as part of an AP story titled “Afghans: NATO Airstrikes Kill 14 Workers.” According to the report, NATO warplanes were tracking Taliban insurgents in eastern Afghanistan and mistakenly bombed a road construction crew while they were asleep in their tents. The deceased workers, civilians from nearby provinces, were paid at the rate of $5.00 a day by Amerifa, a construction company contracted by the U.S. Army Corp of Engineers to build 135 miles of roads for the U.S. military. One NATO spokesman confirmed that two bombs had been dropped with “strong indication that we got a Taliban leader,” but another spokesman commented that the “situation is not clear … [and we are] trying to get a clear picture.” As if to mitigate the significance of the event, the reporter noted that “If confirmed that NATO hit the wrong target, the incident in mountainous Nuristan provice late Monday would be the first major blunder in months.”

It is really hard to know where to begin. According to the NYT, the road had been under construction for a year. And given that the project was under contract with the U.S. Army Corp of Engineers one might think that NATO would have access to its whereabouts. Surely such “blunders” could be avoided, particularly given the history of the involvement of U.S. and NATO-led forces in causing civilian casualties—so called “collateral damage”—in Afghanistan. But accidents do happen and tragic mistakes are made, particularly in war zones. And more, bureaucratic spokesmen are skilled in the rhetoric of obfuscation and the deferral of responsibility. And so, perhaps, what we have is just an ordinary day in the life of a war that seems to know no end. But none of that explains the photograph above which seems to have nothing to do with the accidental airstrike. Why exactly is it here? What purpose does it serve?

Normally we might assume that the photograph accompanying a news article is designed to provide evidence of the reality of the story being told, illustrating its facticity in a “seeing is believing” sort of way. Alternately, it might function to enhance our affective or emotional understanding of an event by creating lines of identification between the viewer and what is viewed. But, of course, in either case, there is the assumption that the thing pictured is an index of the event being reported. Here, of course, there is no direct relationship between the photograph of the remains of a suicide car bombing in downtown Kabul and the accidental deaths of 14 Afghan civilians by NATO military forces in the mountains of Nuristan.

There is probably no shortage of alternative explanations for what the photograph is doing here, but it is hard to imagine how any of them reflect positively on the Washington Post or its motivations. For example, it could be a mistake caused by the pressure of meeting a deadline, but that seems highly unlikely given the source.

An alternate explanation, far more insidious, is that it functions to defer attention from and to mitigate the significance of the accidental deaths of the 14 Afghani civilians. It does this in two ways. First, while the absence of a photograph does not automatically deny the existence of the event being reported, neither does it do anything to enhance our understanding of the event or to enable our identification with the lives lost. Such pictures were available, and the NYT used one in its report and in its daily slide show, but the Washington Post went in a different direction.

Second, the photograph itself invites a perverse logic that models itself after a version of the quid pro quo: Yes, it seems to say, it is possible that NATO “blundered” (although it would be only their “first major blunder in months”), but that is a collateral effect of a war on terror, an insane condition where the enemy is impossible to identify and the most dangerous insurgents are suicide bombers who show no respect for the “rules of war.” And as if to prove the point, look at the photograph. Here we have two soldiers walking past the “ruins” of a nearby house (not actually seen in the photograph but marked by the caption) and a “damaged armored vehicle” destroyed by a suicide bomber the day after the accidental airstrike. That it is an armored vehicle that has been destroyed underscores the power of the threat. Protection is impossible to come by whether you sleep in a tent, live in a house, or drive in a vehicle fortified to withstand attack. And yet, notice that the soldiers are relatively nonchalant and inattentive as they walk by. There is nothing new here. Just as we have seen similar images over and again in recent years, so too have they, albeit up close and personal. It’s just another day on the job.

And so, perhaps, the placement of the photograph with this story is a somewhat subtle endorsement of administration policies. One more indication of the utter banality of war and all that it produces.