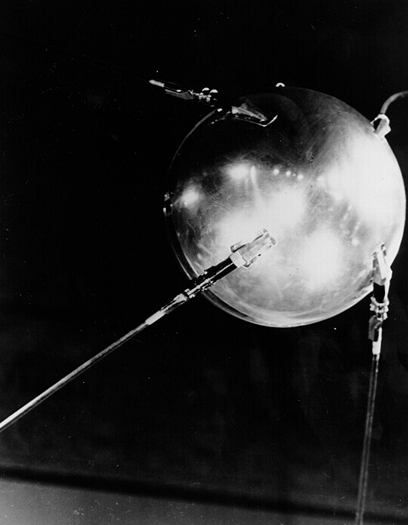

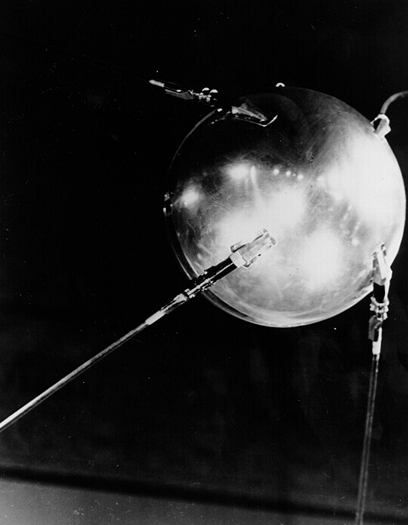

Today is the 50th anniversary of the launch of the Sputnik satellite:

The launch is still seen as the official beginning of the Space Age. Doesn’t that term sound quaint today? “Grandpa, what was the Space Age?” Even so, the anniversary is an occasion for news stories, commemorative events, a documentary film, special (promotional) reports, retail products, and surely a joke or two.

NASA’s home page features presentations on the “50th anniversary of the space age” and on the history of NASA. Perhaps I’m over-reading, but I can’t help but think that the agency is a bit ambivalent about the occasion. Why, when it is their moment of origin? Because they have invested so heavily in “manned” space travel, rather than in the much less dangerous and much more cost effective “unmanned” technologies. Now that the space race is over and the shuttle program has become something like a children’s museum in the sky, that investment seems increasingly mistaken. Even the myth itself is shopworn: space is not the “final frontier,” astronauts are not explorers, science and technology are transforming life on earth rather than transporting it into space.

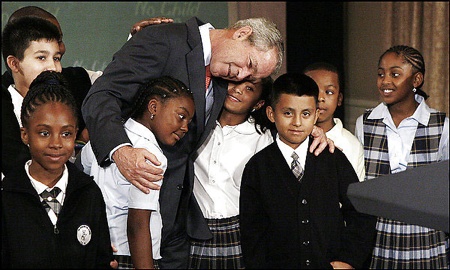

Dreams die hard, however, and I don’t like to be a cynic. So it is that this photograph caught my eye a few days ago:

You are watching spectators looking up at the launch of the Dawn spacecraft, which is beginning an eight-year trip to the asteroid Vesta. There are no teachers on board.

This strikes me as a poignant photograph. It is an image shaped by alignments and contrasts. The craft named Dawn launches at dawn, nature and culture perfectly aligned to carry us forward into a bright future. As it escapes “the surly bonds of earth,” the contrail becomes ever more bright and pure–and distant. As the trajectory bisects the pictorial space on the diagonal, it likewise seems to ride the edge between sunlight energy and the cold blackness of outer space. As the craft arcs cleanly outward, it seems to leave cares, fears, conflicts, all forms of gravity behind.

And we are left behind. That, too, is represented in the picture. Against the bright escape of the machine, a group of human beings look up in awe. They are silhouetted, cast in darkness, as if made of the dark earth. We don’t see individuals but rather something like a group of hunter-gatherers, or perhaps Druids or some religious cult. We are reminded that they are moderns from the cameras being lifted up as if an offering. We see not a premodern cult but rather a camera culture hoping to snare an image. And that image is itself such a tenuous connection to the craft soaring out of sight. One machine surges away into a place we will never go, while a smaller machine only serves to accentuate how we far removed we remain from one kind of heaven.

The rocket launch begins in a darkened swirl of exhaust and soars to light. Those who have come to marvel at the technocratic sublime are left with little patches of light. Data flows back to NASA, and this is real science, also thoroughly human and likely to advance knowledge that can benefit life on earth. We don’t need to be on Vesta, and the machine will do the job. But it can do nothing to stop the yearning, while the camera can remind us that even as we dream of escape, we do so while living as human beings have always lived–sharing a common fate, bound to gravity and darkness, yet capable of joining together in a common life. All are bound by the same limits, members of the same tribe.

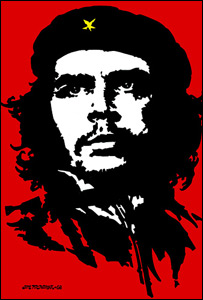

I like the photograph for another reason as well, one that comes from comparing it to the file photo of Sputnik. In that image, we see only the machine, its metallic surface enhanced further by sharp black and white contrasts. It is a machine for a hard environment of energy and void, where neither death nor life have any meaning, only thrust, structure, data. The satellite looks self-sufficient, the epitome of modern design that in turn represents a technocratic future. Perhaps the commitment to lifting up astronauts was, in that context, a kind of humanism. If so, that moment also has passed. Now we stand as if in the second photograph. Our machines go not in advance of us, but in place of us, whether into space or into the ocean and the bloodstream. But they go for us, not as an end in themselves. After all, we are back in the picture.

Sputnik photograph from a NASA commemorative photo gallery; launch photograph by John Raoux/ Associated Press.

2 Comments