The English word “cosmos” is defined by Websters/Random House as “the world or universe regarded as an orderly, harmonious system.” The word derives directly from the Greek kosmos, which could mean the world or universe, and also an ornament and the mode or fashion of a thing. The connection between the, well, macrocosmic dimensions of the universe and correspondingly microcosmic scale of an ornament–think of an minutely detailed earring–came in the Greek mind from a shared sense of order. That connection is lost in English usage, where “cosmic” and “universal” go in one direction and “ornamental” and “fashionable” in quite another. At times, however, it is still there to be seen. Let’s start with this image:

This is a photograph of a carefully prepared martini. The image first appeared in a Chicago Tribune Magazine photo-essay on “cool cocktails” and ended up as one of many images in an end-of-the-year review. This is a better fate than what awaits most photographs of food or drink, and for good reason. This image is a stunning example of modernist design at its best. It also is optically interesting, not least because of how the light in the glass, whether of the cocktail or camera or both, makes an X pattern in the conic section, and of how the colors in the drink are repeated as a spectrum on the perimeter. These designs suggest another structure underlying the aesthetic design of the cocktail, the natural ordering of the physical universe. Against such cosmic extension, the drink is but an ornament yet something differing from the universe only in scale, not in aesthetic significance.

Whatever their worth, I was brought to these thoughts not by the photograph itself but because it inadvertently made me think of another:

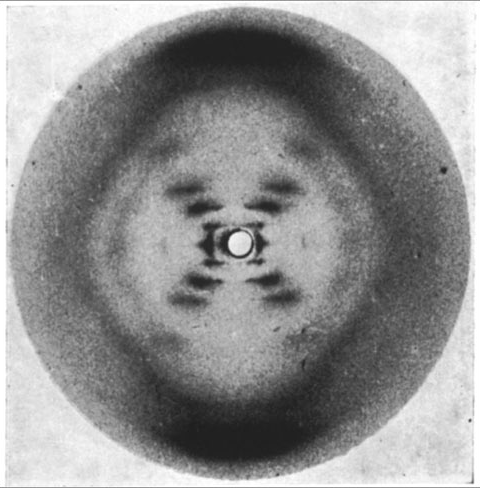

This is the now famous Photo 51 taken by Rosalind Franklin in Kings College London in 1952. You are looking at an X-ray diffraction image of DNA. And not just any image X-ray diffraction image of DNA, but the one that provided the key missing piece of information for Watson and Crick’s discovery of the structure of the DNA molecule. (Two of the three named above received the Nobel Prize for this discovery; want to guess which one was left out?) It’s a stretch to see the structure of life in a photograph of a martini; indeed, a physicist might point out that a more parsimonious explanation is available. But I love the aesthetic correspondence. Each can be ornament and each cosmos to the other. One can see structure within design, or design within structure. (And this without any religious implications, by the way.)

Universe or ornament, fashion or nature. You don’t have to be Greek to see that they can be the same. It does help to be open to allegory, however, and to chiasmus and, perhaps, to quote Wallace Stevens, to the Motive for Metaphor and “the vital, arrogant, fatal, dominant X.”

Photographs by Bill Hogan/Chicago Tribune (February 2, 2007); Rosalind Franklin, Kings College London (1952).

[…] by Robert F. Bukaty/Associated Press. For an earlier post on aesthetic design in nature, see The Photographic Cosmos. The beauty is good idea was a stock item in the Renaissance; see, for example, Castiglione’s […]

Rosalind Franklin died of cancer before the Nobel Prize was awarded to her partner along with Watson and Crick. Nobel Prizes aren’t given posthumously, and therefore, she did not receive one. Undoubtedly the hundreds of unprotected x-rays she performed contributed to her death.