The recent economic “downturn” is being treated as a world historical event and that means that photo editors have been searching furiously to find the iconic image of the event, a problem made somewhat difficult by the fact that economic traumas are not nearly as easy to visualize as wars or natural disasters. And the result is somewhat amusing as one after another the various newspapers emphasize an almost endless parade of images of stock brokers and fund managers from around the world depicted in various degrees of emotional distress, mute witnesses to a roller coaster of numbers scrolling across black and green screens and monitors. Elsewhere, and at the same time, news stories wonder when the effects of the most recent “bubble” to burst will be felt in the “real economy.” To be sure, the effects of the current economic situation are palpable; many who don’t deserve it face serious financial hardships in the years ahead, and I don’t mean to diminish the significance of that in any way. And yet, two photographs that appeared in tandem as part of a slide show at The Seattle Times this past week (10/17/08) put it all in a perspective that it would be good for us to think about.

The first image is of a young child in Lagos, Nigeria playing in a dirty and rusted out oil drum in what appears to be a garbage dump of some sort. The picture is used to promote World Poverty Day and it channels all of the pathos of images commonly used by NGOs to encourage charitable contributions—perhaps you can’t solve all of the poverty in the world, such ads typically intone, but surely you can save this child for only pennies a day. The power of the appeal is simple and direct: the child is looking directly at the camera in the manner of a demand and all we have to do is substitute the image of our own child (real or imagined) to understand the pattern of identification that is being encouraged.

The problem, of course, is that we encounter such images so frequently that it is easy to become inured to their appeal or simply to look past them as if they were not their at all. And I might have done exactly that but for the photograph that followed it:

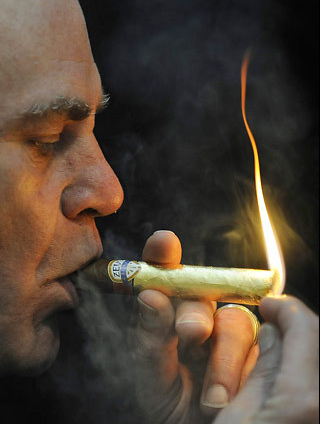

What we are looking at is a man smoking a “Golden Zeus,” a cigar that has been dipped in pure gold and is “on display” at the Millionaire’s Fair—a luxury goods and trade show “open to the public”—being held in Munich. Unlike the photograph of the child in Lagos, there is no demand made here upon the viewer; the smoker is completely self-absorbed in his own private desires, a decadent pleasure offered up to the “public” (by some accounts over 40,000 people paid the $50 admission fee to attend the show and we can only assume that most were not millionaires) for its own perverse consumption. It is, in a phrase, an exhibition of “class voyeurism.” Left on its own, the photograph would operate in a pornographic symbolic economy, but of course when placed in direct contrast to the earlier photograph it is hard to imagine it as anything but obscene.

We could go on at some length about the fundamental contradictions of global capitalism captured in the opposition between the two images, and there certainly would be some value in doing that. But there is a slightly different point to be made, for the juxtaposition of these photographs at this moment in time stands as a potent reminder of two key facts: (a) for all the bubbles that burst in the financial sectors, and for all of the claims that capitalism will be fundamentally transformed in the process (and it might well be), nevertheless, the desire that animates the underlying value system of a capitalist economy is far from diminished—and no amount of government regulation is likely to change that; and (b) while much has been lost by many as a result of the current crisis, and while more still is likely to be lost, the measure of that loss is best calibrated against how much we actually had to lose.

As we search out the impact of our current economic woes on the “real economy” it is perhaps prudent to keep both facts in focus.

Photo Credit: Sunday Alamba/AP; Christof Stache/AP

I am of the opinion that more of the world’s unneccesary excesses should be given the same treatment as poverty, war, famine and disease. They are no less abhorrent, but instead of being treated as damaging to society, they are something to aspire to and attain. Imagine if you reported on haute couture, $100, 000 banquets and golden cigars in the sme manner that one would report on genocide, ie as something that should not and need not happen. By addressing these issues in this way we might in fact be helping the ‘boy in the barrel’ in a much more profound manner.