The New York Times ran a story yesterday entitled “In the Middle of Nowhere, a Nation’s Center.” The subject was the geographical center of the U.S., which is a windswept prairie in Butte County, South Dakota.

There is a monument, of course, but it’s in the nearby town of Belle Fourche. Most visitors–yes, there are visitors–are content to take their pictures there rather than trek out to the actual spot. The reporter’s sense of irony is light, in keeping with his respectful attitude toward the folks actually living there. The story even includes a feel-good ending. “But then, in this remote, still place, there comes a strange sense of reassurance: that in this time of uncertain war and near-certain recession, of home foreclosures and gas at $4 a gallon, at least somewhere in this nation a center holds.”

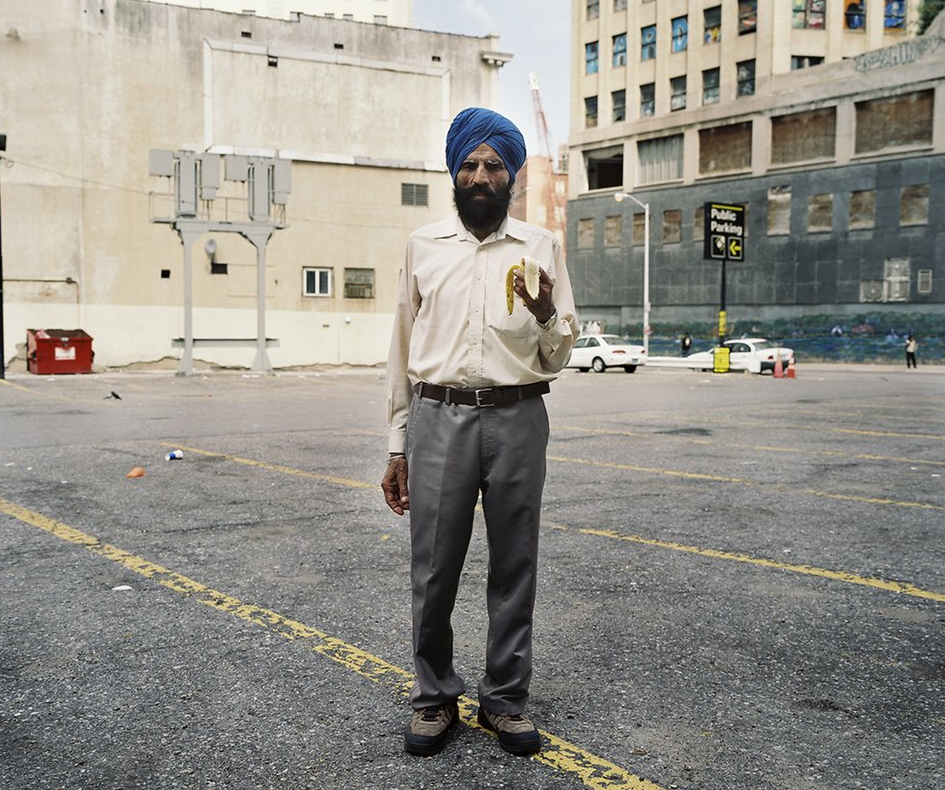

But does it hold? Or, more to the point, why would it not hold when no one wants a piece of it? And isn’t the scene pathetic? The abandoned landscape reduced to flee market status by the hand-scrawled sign? The Times story provides an inadvertent chronicle of how rural America, once vying for its place in the nation’s prosperity, has been bypassed for roads leading elsewhere. And let me add that $4 a gallon gas hurts them a lot more than it hurts you. But you already are accustomed to not seeing them, and there are no pictures of people in the slide show accompanying the story. All you have to do to complete efface the unpleasant fact that people still live there is remove the sign.

This is another photo from the slide show, and the last of the set. Now we have a classic shot of America the Beautiful, the mythic landscape of the American West and its message of endless possibility. That image was already in the first photo, but there it sets up the irony of the ragged sign, which in turn changes the magnificent vista into a desolate “moonscape.” Ironically, the sign declaring a center highlights its emptiness. When that emptiness is not marked by the visual excess of a verbal text obviously added to the scene, a tawdry bit of culture marring nature’s grandeur, then one can see fullness, a richly symbolic affirmation of national potential. Like the wind, endless, waiting to be harvested.

Or, like the sign, symbolic in another sense. With his assurance that “at least somewhere in this nation a center holds” the reporter offers a refutation of W.B. Yeat’s famous indictment of modernity in “The Second Coming.” But the center in question is not holding, not in South Dakota, anyway. Agribusiness, agricultural policies, transportation policies, and other very real historical forces are draining the land of people, soil, water, you name it. America has invested heavily in centrifugal processes, and seems to have little time to be centered, much less balanced, reflective, or attentive to its own.

Photographs by Angel Franco/New York Times. For another perspective on the Great Plains and what one can learn there about being centered, see the wonderful book Dakota: A Spiritual Geography by Kathleen Norris.