For all the excitement of the US presidential election, Iraq and Afghanistan are still war zones where people are struggling to live in conditions that fall far short of the American Dream. You wouldn’t know it from the American media, however. Fortunately, there are other reminders of both the damage done and the people still there–in short of obligations that remain.

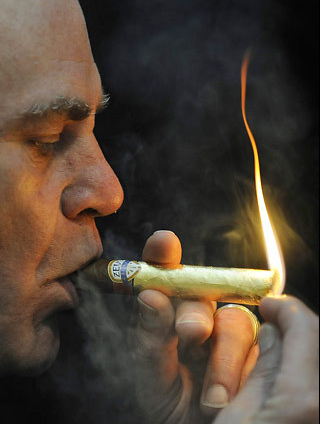

Baghdad Calling, by Geert van Kesteren, is a remarkable collection of images taken by ordinary citizens in Iraq and elsewhere in the Iraqi diaspora across the Middle East. The photo above has strong resonance with professional war photography. Coverage of the Iraq war has included many scenes framed by a car window, and of dead bodies on the ground which harken back to the famous photograph by Mathew Brady of “Federal Dead on the Field of Battle of First Day, Gettysburg, Pennsylvania.” But the photo above is hardly a study in artistic allusion. Knowing that this is a scene from daily life gives it a special fascination and horror. This is not “the war” but somebody’s neighborhood, a place where kids might be scrounging around looking for cool junk. Or worse, the car could be driving through the back lot because those inside are hoping they won’t find the body of a loved one.

That emotional response to the photograph is supported by a realism that makes it a worthy heir of Brady’s image. Brady showed the world that “the fallen” become corpses that bloat in the heat. Now look closely at the photo above. The man on the right has his arms tied behind his back. One of those on the right may have been dismembered. Despite our familiarity with photographs of destruction, this is not what one wants to see while riding in the car. Welcome to Baghdad.

And what would you do if you had to live amidst violence? Well, one solution is to get a hot car.

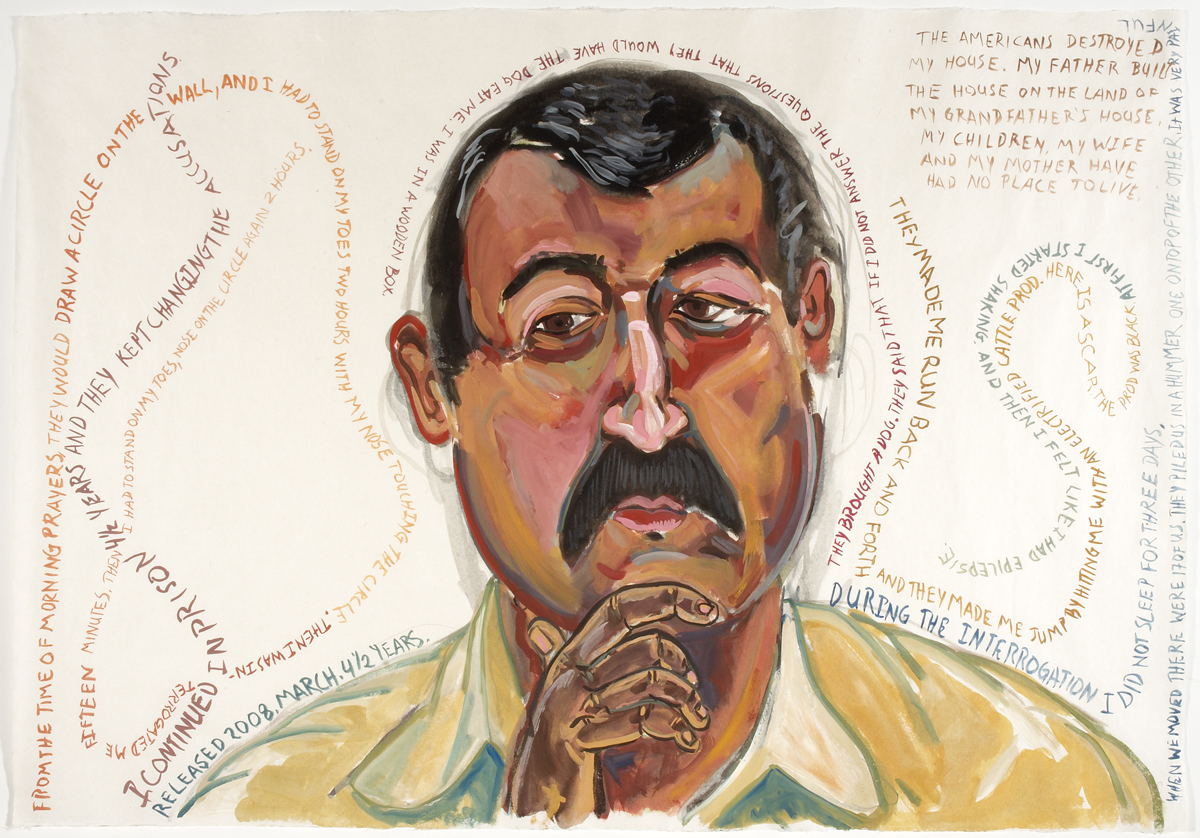

This photograph may be more jarring than the one above. It certainly is not what one expects to see coming out of coverage of the war. Nor would you see it at an automotive fair or a fashion show. This guy is not rich and not cool, neither sleek nor fast, yet he’s doing what he can to to make that small car into something beautiful, and his life into something of his own making.

The scene is perfectly still–perhaps even more so than the first, which carries the sense of the interrupted motion of the car and the transitoriness of human life. Yet the motionless pose contains a cascade of contrasts. This is a domestic scene, not men at war; his casual clothes are further diminished by the sheen of the car; the car is diminished by the ideals of automotive power and design it evokes; he appears clownish by comparison to the Hollywood fashions implied by the hat, sunglasses, and car. The result is a complex emotion of both the vicious derision within all social hierarchy and astonishment or even admiration at his being there at all. Isn’t he supposed to be dead, or killing someone, or at least staying out of sight behind the imperial guard?

This image documents reality just as deeply as the first does. Where one exposes how war terrorizes people while turning them into trash, the other documents the sheer persistence of the desire to live a normal life. The image captures a triumph of self-respect, and precisely because he can stand up even though everything he has is less than ideal. That is exactly how each one of us gets through the day.

The problem, of course, is that some people have to do so against much worse obstacles than others. And what is needed is not sentimentality, but political accountability.

Van Kesteren’s work is also part of an exhibition “On the Subject of War” at the Barbican Art Gallery through January 25, 2009. Note also the commentary by Geoff Dwyer at The Guardian. You can link to the book at Amazon.com here, or to his earlier book on the Iraq war, Why Mister, Why?

4 Comments