By Guest Correspondent Aric Mayer

On page 194 of Glamour Magazine’s September issue, in a three-inch by three-inch photograph by Walter Chin, 20 year-old model Lizzi Miller sits on an apple crate in a thong.

She leans forward slightly, her arm covering her breasts, a confident and radiant smile on her face. There is a small roll on her belly and actual curves on her legs and arms. At size 12, Lizzi is the size of the average American woman.

That little belly roll is pure rebellion in the fashion and beauty industry, and it’s the sure reason why this image has had such an incredible effect. Images of Lizzi have been published before, and in each (that I have seen) she is doing what models do, tucking in, tightening, lifting up. Here she appears relaxed and unguarded, and is all the more beautiful for it. Relief and appreciation poured out from readers and can be read in the 1000+ responses posted on Glamour’s website.

Equally significant to the reader response is the extreme rarity of a photograph like this in the context of a fashion magazine. To be clear, this image was intentionally created to have this impact on its viewers. As Glamour Editor in Chief Cindi Leiv says, “We’d commissioned it for a story on feeling comfortable in your skin, and wanted a model who looked like she was.” The image isn’t rare because it can’t be done. It is rare because it is selling something outside of the consumer logic of the fashion and beauty industry.

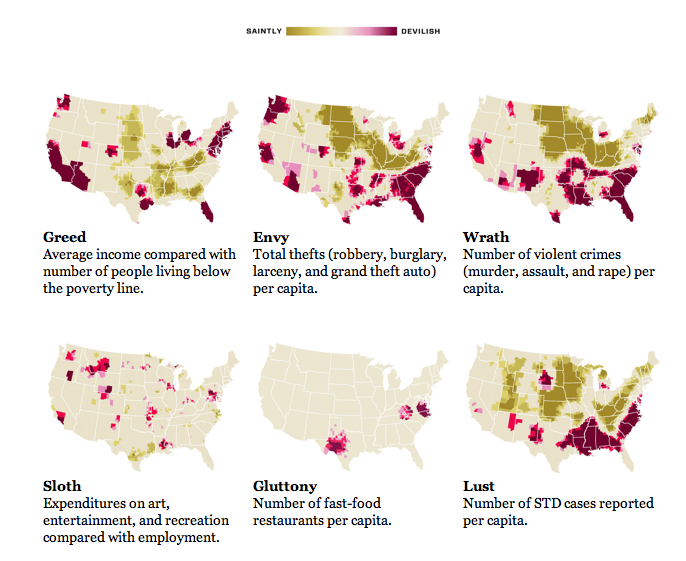

Professor Jeremy Kees at the Villanova School of Business ran a study demonstrating how the skewing of body norms increases the effectiveness of advertising. In his study women were presented with images of skinny models in a commercial setting and were then tested as to how they would respond. The women exposed to the images of overly thin models tested as feeling worse about themselves, but tested with more positive attitudes about the products being sold. Women exposed to normal sized models had no diminished sense of self, but tested with less favorable attitudes to the products being sold. See the logic at work here?

The stereotypically thin model image serves a very pragmatic purpose in generating an overall climate of desire and consumption that serves the fashion industry at the personal expense of the audience. Lizzi Miller, as she appears on page 194, defeats this basic exchange between the readers and the advertisers, and the reader responses are permeated with a release of the pressure both to conform and to consume. It is also significant to note how far the difference is between talking about body norms and actually showing them.

Here is where it gets really interesting and exciting if you would like to see more of this kind of work. Judging from the comments on the Glamour site, thousands upon thousands of readers do.

The magazine publishing industry is in a state of suspension. Trapped between increasing online competition and falling ad dollars due to the recession, many publications are scrambling to figure out what the future holds.

You have the power to talk back to the magazines through social media. And you have the one thing that they absolutely must have to survive–your attention. That attention is a commodity that is traded by magazines with advertisers and converted into real dollars. If you withhold your attention, magazines fail. If you lavish it, they thrive.

Two things need to happen soon, and they need to be reader generated.

First, there needs to be a reader generated movement to request magazines to give an honest and full disclosure of their internal retouching policies. The audience has a right to know how the images are being manipulated. Every image receives some form of digital manipulation. Retouching disclosure statements would simply explain in specific terms what a magazine allows and doesn’t allow in their image processing.

Readers would be able then to appreciate a magazine with a more clear understanding of what they are looking at. It would also be a commitment from the magazine to its readers to work within a set of self-described limits. If even just a few major magazines made a point of communicating their limits to their readers, it would set a precedent in the industry with far reaching implications.

The second thing that needs to happen is going to sound crazy. There needs to be reader-generated campaigns to raise magazine subscription rates.

I realize that this seems counter-intuitive, but here is how it works. If you are buying subscriptions on the cheap, the only hope magazines have to make money is from advertisers by selling your attention as a commodity. After all, you aren’t really paying for the magazine. But if you are willing to pay more, suddenly you, the reader are starting to pay for the content and the magazine has to work for you, not the advertisers. Remember Kees’ study? If you aren’t going to pay for those pages, advertisers will, and it will serve their purposes, not yours.

This post is adapted from Confessions of a Bone Saw Artist by Aric Mayer

5 Comments