By guest correspondent Rachel Hall

Times Square is an iconic point of arrival for aspiring actors, international tourists, and now criminals. Last week, the FBI announced that it would begin screening wanted fugitives on an electronic billboard donated by Clear Channel Outdoor. The police and the press have long collaborated on outlaw displays, but the FBI’s move is significant in terms of both scale and placement.

Compliments of The Today Show, you can see Belle Chen, Assistant Special Agent in charge of the FBI’s violent crime unit in New York, and Harry Coglin, President of Clear Channel’s Outdoor New York staged like two television personalities hosting the ball drop on New Year’s Eve.

The FBI’s larger-than-life notices are reminiscent of Andy Warhol’s Thirteen Most Wanted Men mural commissioned for the 1964 World’s Fair. In a characteristically cheeky moment in The Philosophy of Andy Warhol, the artist provided a caption for his mural: “Nowadays if you’re a crook, you’re still considered up there. You can write books, go on TV, give interviews—you’re a big celebrity and nobody even looks down on you because you’re a crook. You’re still really up there. This is because more than anything people just want stars.”

The wanted poster’s authoritative tone inspires fear, moral indignation, and patriotic fervor for law and order. And yet as Warhol understood, the public’s desire for images of crime and punishment often exceed the bounds of patriotism in order to produce pleasures based in outlaw identifications, frontier nostalgia, or the desire for a dose of danger in everyday life. Like Times Square, the wanted poster simultaneously attracts and repels us. In his book, Where the Ball Drops: Days and Nights in Times Square, Daniel Makagon observes: “Times Square is a place, both real and imagined, where historical images of a vibrant public sphere collide with contemporary cultural practices triggered by a proliferating consumer society. It is a place where some long for increased security in public space while others gravitate towards its historical reputation for sex, sleaze, and the thrill of danger” (xiv-xv).

The FBI’s giant, electrified wanted poster participates in ongoing battles over public spaces increasingly claimed by the interests of multinational corporations. Clear Channel Outdoor promises to: “Reach the mobile consumer.” Currently, the company has a presence in 44 U.S. cities and 31 other countries, including China and Russia, as well as many countries in Europe, North and South America.

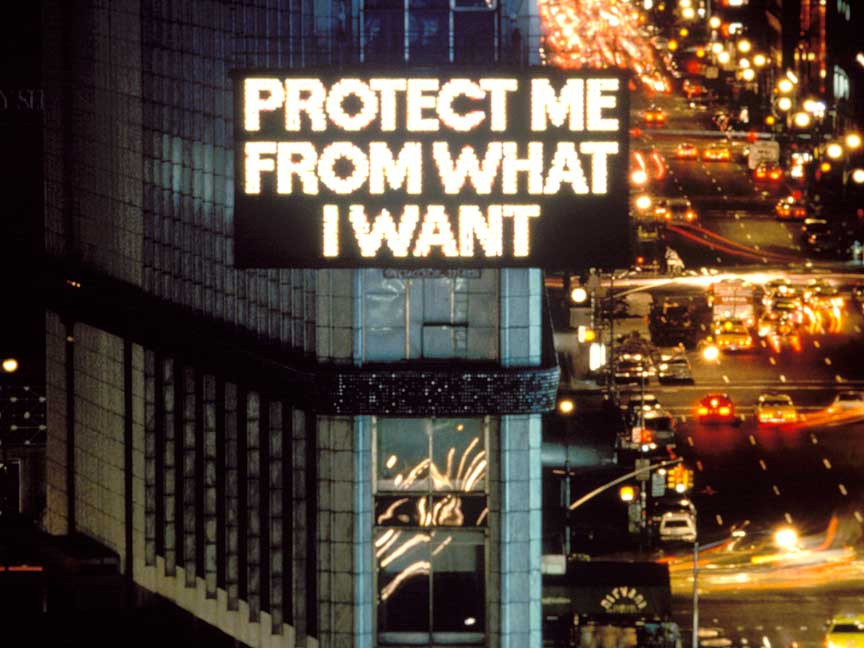

Artist Jenny Holzer protests the privatization of public space in cities around the world by installing screens on a scale like and in prominent locations characteristic of those currently managed by Clear Channel, from which she transmits critical provocations.

Holzer is trying to confront the media-security-advertising complex directly, but she is outgunned. Clear Channel’s joint venture with the FBI is modeled on an earlier partnership between Lamar Outdoor Advertising and Crimestoppers. Over the last decade or so, Lamar has been at the center of heated legal disputes in municipalities across the U.S. In each new market, Lamar finds itself locked in a struggle with local community members who fear the flashy signs will be a traffic hazard or resent having to bask in the glow of billboards each night. Over time, the company has become adept at branding its electronic billboards as part advertisement, part public service, stressing the fact that the company donates space and time to screening wanted fugitives and AMBER alerts. Likewise, in his report on the FBI’s “Broadway debut” for the Today Show Pete Williams told home viewers: “And these electronic billboards can also be used to spread AMBER alerts and seek help finding missing persons.”

The “public service” on offer from companies like Lamar and Clear Channel is ideologically loaded and leans heavily toward the privatization of public space. The wanted poster and missing notice symbolically mark the border between “home” and the external dangers that threaten its sanctity. In the context of Times Square, home is what the aspiring actor leaves behind on her journey to stardom. It is the rights of a particular configuration of family that renders homoeroticism suspect, if not criminal, in Warhol’s ironic mural. And it is the rights of the family on tour that Mayor Rudy Giuliani violently defended in street sweeping campaigns of the 1990s, which banished sex shops and paved the way for the Disneyfication of Times Square. Like Times Square, and the billboard for that matter, the wanted poster has a long history of animating the tension between private interests and public spaces.

Photograph of the Jenny Holzer installation by John Marchael, © 2007 Jenny Holzer, The Artists Rights Society/. “Spectacolor electronic sign. Times Square, New York, 1986.”

Rachel Hall is an Assistant Professor of Communication Studies at Louisiana State University and author of WANTED: The Outlaw in American Visual Culture. You may reach her at rchall@lsu.edu or visit her website. [Thanks to Chris Hardy for calling my attention to the Today Show piece.]

Rachel, I love your book, *Wanted*, in part b/c the historical research you’ve uncovered & woven together reveals how security in U.S. history long has drawn on private entities to “protect” the public good. Yet, the involvement of massive private corporations today, like Clear Channel, do make me feel like this pattern is the same, but different. Do you think contracting with a media conglomerate (as opposed to a security entity, like the Pinkertons) shifts the stakes of involving private entities in public policing? Visually? Politically?