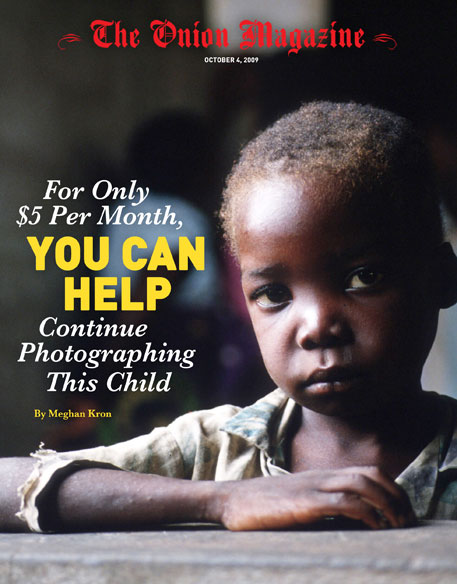

As much as I’m committed to progressive photojournalism, I have to like this cover from the Onion:

The nice touch of imitating the New York Times Sunday Magazine only gilds the lily, as the photographic convention being lampooned is used everywhere: glossy magazines, newspaper ads, direct mail, web sites, billboards, photography books, TV documentary trailers, and more. You can donate or you can turn the page, but you can’t avoid seeing the picture.

There actually is a continuing debate among human rights advocates and cultural critics about such rhetorical appeals, and the Onion cover neatly summarizes a number of key arguments. First, the problem of human deprivation is given a human face, but at the cost of reinforcing damaging stereotypes. The poor (and the Third World) are portrayed as essentially dark, passive, weak, simple, and dependent (need I add that images of want usually are of women and children, and often female children?). Second, analysis has been replaced by the direct emotional impact of the visual image, and reasoned commitment by a sentimental appeal. You are asked to help an individual child who seems so close that you could pick him up and hold him, although the money will in fact go through many hands and may make no difference whatsoever in his life. Third, the poster child’s innocence and obvious dependency dissociates charity from any serious attention to structural change, an inattention that often excuses how the US and other affluent nations are also among the causes of the problem. Fourth, the magazine’s tony production values suggest that there is money to be made off of human misery, and even the photographers’ mixed motives are exposed–indeed, are the point of the parody. Fifth, the enduring contrast between deprivation and the affluent world of the magazine audience is all too obvious: $5 per day is not going to set anyone back on this side of the street, and yet mere charity is all that is imaginable, not serious redistribution. Finally (for now, anyway), the audience may experience the perverse pleasure of indulging in feelings of pity about the suffering of others while giving their middle class conscience an easy out. Whether I donated or not, I gave at the magazine, so I can feel sorry for the poor and good about myself–and turn the page.

Actually, there are additional criticisms, and all of them can (and have been) developed in great detail. So why does the debate continue? There will be many reasons, but one is inescapable: the images work. Despite having become highly conventional, images of needy children open purse strings. Furthermore, if the appeal is not effective, no one else is likely to step in and make up the difference. So, damned if you do and damned if you don’t, and most advocates conclude it is better to do than to do nothing.

Other options remain, however, especially for photographers looking for another angle on a problem. Instead of the exceedingly conventional character of the typical humanitarian image, one might want to ponder this photograph:

Of all the images of the Haitian disaster, I find this one to be surprisingly eloquent. And it shouldn’t be: I shows no people, only property, and instead of the close-up that might grab one personally, we have the distant and distancing impersonal perspective of an aerial view. Nor is it an action shot, and there are no dramatic special effects such as smoke and fire. One might think the most likely reaction is simply, “well, at least it’s over, and although there is a lot of damage, it’s only property damage, not lives lost.”

That’s not what I see or feel when caught in this photograph. Somehow it reveals the massive dislocation that remains after a catastrophe–the profound wreckage, disorder, waste, and raw mess that remains. It also reveals that disaster has its own full weight of inertia. Nothing that has been crushed together in that picture can be pulled apart and moved back or out of the way, much less restored to what it was, without labor, effort, work, and much more of the same, just to get back to even. And imagining it being sorted out–or, more likely, bulldozed–starts one thinking about how it got there, and about what ought to be put back and what ought to be built anew but differently. The photo reveals the enormous forces that were involved, and requires that one imagine what the city should be. In short, it demands more than is required to give five bucks to a child (or a photographer). And if people aren’t evident, neither are the denigrating associations that pull people down.

Communication depends on conventions of representation, but it can become trapped in them. As much as humanitarians rightly insist on the value of the individual person, there may nonetheless be times when we don’t need to see another face. Given the scale of the humanitarian disasters now and to come, more thought might be given to how even things can speak.

Onion Magazine cover from issue 45-45, May 2, 2009; photograph from Chile by Natacha Pisarenko/Associated Press.

This is great analysis.

Please can I republish this on the blog at adevelopingstory.org, which is specifically set up to debate this issue. David Campbell, Charlie Beckett and Asim Rafiqui are all contributors. You can also see similar thought on this post I wrote recently for the Nieman Storyboard:

http://niemanstoryboard.us/2010/03/18/duckrabbits-benjamin-chesterton-on-the-blindfolded-photographer/

THANKS

Benjamin

Benjamin: Sure, you can use it, and thanks for the additional links to keep the conversation going.

Robert,

thanks very much. I’m a great admirer of your work and your voice will certainly add depth to the debate.

Benjamin

I totally agree with your arguments, but what can be done to change the way charities (not all, but many) raise money? In order to alter the practice of charities attracting dollars with “the value of the individual person” someone would first need to prove the economic strength of an any alternative option.

I agree with your analysis of the above birds-eye image (who is the photographer by the way?), but are people flipping through a magazine going be moved by it enough to donate even $5? Will they be as likely to pause for this image as the image from the faux cover? I’m not so sure. But what does seem evident is that until charitable organizations can find a economically viable alternative, it seems unlikely that we’ll see a change in strategy anytime soon.

Maybe someone will take a “risk” and start using the types of images you discuss—those that avoid “denigrating associations” and convey a broader view of the problem at hand—and start a conversation within the charity world about the diverse options of effective imagery available. But do you think that will happen anytime soon? I hope so.

Social comments and analytics for this post…

This post was mentioned on Twitter by nocaptionneed: When Things Speak Louder Than Faces (http://bit.ly/bbvZFS)…

Great post thanks.

I work for an NGO which is grappling with exactly this and it manifests in conflict between campaigning and fundraising teams constantly. We have guidelines on using empowering images and that fundraising materials must not reinforce the stereotypes we (and more importantly those pictured) are struggling to challenge. But as you say, the fact is they work and get a better financial response rate. At a time of recession, when charities and NGOs are running out of money and loosing traditional sources, this argument becomes more powerful.

I really don’t know what the answer is. The campaigners keep campaigning and the fundraising keep trying to fundraise, so we’re going to have to keep having these fights. I would like to involve the public more in this debate and start getting them (I don’t mean to disassociate myself, but you know what I mean) to start questioning their motivations. Can’t guarantee it will lead to greater giving though…

Great post – i wrote something similar last week – http://www.globalpovertyproject.com/blog/view/101, and was amazed at the reaction i got on facebook, twitter and via email from people who grapple with this issue.

Would be interested in your thoughts on the post

[…] a clear sense of the depth of human tragedy, but here the structure of feeling inclines more to the conventional sense of pity and compassion one finds in any sort of philanthropic venture. While the original McCurry photograph demands […]

Sinon: Thanks for the input. Your post and the comments it received capture a fair amount of the emotional complexity involved, and I think everyone agrees that we ought to be able to respect people and still be willing to help them. And those contending with poverty have much to teach to the more affluent world, so we need to connect societies, not just individuals (the abject child and the affluent donor). See also David Campbell’s recent post on how images of children strip away social context. http://www.adevelopingstory.org/2010/visualizing-‘africa’-from-the-lone-child-to-the-middle-classes. These issues also will be discussed at a forthcoming conference in NYC: http://www.nyu.edu/ipk/conferences/visual-citizenship-conference/. As for why the image of the child works, I’ve got an answer that is too long for this space, but, briefly, liberal societies expect adults to be self-supporing, but the child is innocent (not part of the problem), portable (can be imagined in your world despite cultural differences), naturally dependent (requiring help), and can evoke a parental response (loving acceptance and support). In addition, the photograph of the child solves a basic moral dilemma that was set out by the philosopher Peter Singer in 1972: only a moral monster would not incur expenses to save a child drowning in a pond, so why don’t we do the same for a child in a pond on the other side of the world? The photograph helps to reduce the psychological distance that interferes with moral response. Not completely, of course, as you are not a moral monster if you don’t respond, but enough to make some people donate and others feel manipulated, perhaps while still donating.

[…] might otherwise be regarded as a collective or social issue? Is it the case, as Robert Hariman has argued, that sometimes “things speak louder than faces.” # For someone developing a visual story, […]

[…] http://www.nocaptionneeded.com/2010/03/when-things-speak-louder-than-faces/ […]

[…] might otherwise be regarded as a collective or social issue? Is it the case, as Robert Hariman has argued, that sometimes “things speak louder than faces.”For someone developing a visual story, the […]

[…] might otherwise be regarded as a collective or social issue? Is it the case, as Robert Hariman has argued, that sometimes “things speak louder than […]

[…] might otherwise be regarded as a collective or social issue? Is it the case, as Robert Hariman has argued, that sometimes “things speak louder than […]

[…] below. This photo was given as an example of how things might affect us more than faces of people. (http://www.nocaptionneeded.com/2010/03/when-things-speak-louder-than-faces/) found through the above link to no caption needed…”but often provided” with […]

[…] below. This photo was given as an example of how things might affect us more than faces of people. (http://www.nocaptionneeded.com/2010/03/when-things-speak-louder-than-faces/) found through the above link to no caption needed…”but often provided” with the reference to […]

[…] (2010) when things speak louder than faces,No caption needed,[online at] :http://www.nocaptionneeded.com/2010/03/when-things-speak-louder-than-faces/ (re-accessed April 5 […]

[…] https://www.nocaptionneeded.com/2010/03/when-things-speak-louder-than-faces/ […]