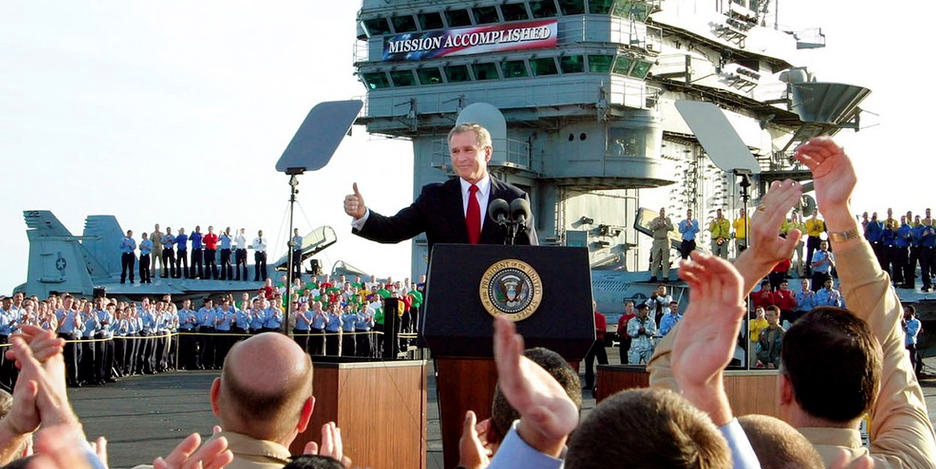

The war began officially on March 19, 2003, and 43 days later President Bush declared “Mission Accomplished” after landing a S3B Viking “Navy One” aircraft on the deck of the USS Abraham Lincoln. That was on May 1, 2003. This past week—7 years, 3 months and 10 days later, to be exact—and with considerably less fanfare—the “combat phase” of the war came to an end as the last of 30,000 America’s combat troops crossed the border from Iraq to Kuwait en route to the USA. I might feel slightly better about this if we were not leaving 50,000 “non-combat troops” behind to lend “technical assistance” to the Iraqis, a fact compounded by the lingering memory that the war in Vietnam was fought with “military advisers.” All of that notwithstanding, my first thought was that it would be somewhat churlish to feature the above photograph on this occasion. After all, surely President Bush cannot be responsible for the decisions made by President Obama … can he? But then I recalled that the initial motivation for the invasion of Iraq was to seek out and destroy weapons of mass destruction; weapons, lest we forget, which were never found and were in all likelihood a neoconservative fantasy from the outset. “Mission Accomplished,” indeed.

Bringing any troops home is nevertheless a moment for some celebration, and no doubt in the weeks ahead we will see more than a few photographs of loved ones as they jubilantly reconnect at the end of a gangplank or on the tarmac of an airfield. It is, after all, a convention of war time photography. But as we view these images we have to be sure to see past the immediate burst of joy to the long and extended pain and trauma—both physical and psychic—such soldiers and their families will endure. It is unlikely that such images will be taken or if they are that they will be featured; and even if some are, it is a sure bet that they will not circulate widely or that they will quickly fade from memory as too painful to recall and attend to for very long.

As much as coming home can be a moment of celebration, so too is it in some measure a moment of mourning for those who return. I was struck in this regard by expressions on the faces of soldiers leaving or preparing to leave Iraq. Where one might expect to see joy or relief most images showed men—and it is notable that such images were specifically of men, not women—bearing a serious if not actually somber countenance. The photograph below, appearing in a Washington Post slide is particularly poignant in this regard.

Shot at night and from within the hold of a cargo plane preparing to leave Iraq, the image has a degree of sober familiarity to it. We have seen scenes like this before, though typically the “cargo” being loaded is not a pallet of duffle bags, but rather flag draped coffins. What makes this image particularly eerie is the way in which the workers appear to be mourning the cargo as if this were a burial pall. That is hard to imagine, of course, because it defies our experience. How could one possible mourn the return of cargo which metonymically stands in for the return of the troops? But then why would troops about to return home not exude joy? The problem is that our experience of the war is mediated, and from a distance; not being there it is impossible to know what the troops who were there actually experienced—or what their return to their former “civilized” lives might entail … what and how and why they might mourn.

The photograph above is thus in some ways a reminder of the difficulties that we might all have in adjusting to the return of fellow citizens form the war zone—friends and family and strangers alike. For just as in the image, shot at some distance and at a slightly oblique angle with a wide angle lens, our plight might be to witness but not actually to participate in the performative space of action in any direct way. Put differently, the photograph is perhaps an allegory for the wide range of ways in which war entails mourning. For those who were there and for those who were not. Lest we forget.

Photo Credit: J. Scott Applewhite/AP; Ernesto Londono/Washington Post

This photograph can also be read as exposing the myth of war, chief among them the myth that “we” or soldiers do not desire war. As Chris Hedges ably points out in his insightful book “The Myth of War” there are any number of positives associeated with war, developed as a means to justify the horrors and sacrifices and reqork them into the heroic. Tales of troops serving multiple terms in Iraq also reveal some feeling of instense motivation, mission, and fraternal solidarity—enclosed in a wish to not leave until the mission is truly accomplished, peace established, or as long as fellow soldiers are there. There is a strong narrative of belief in and devotion to the effort that might be revealed here in the somber attitides, even though we assume all returning service members are experiencing joy upon leaving the battle site.