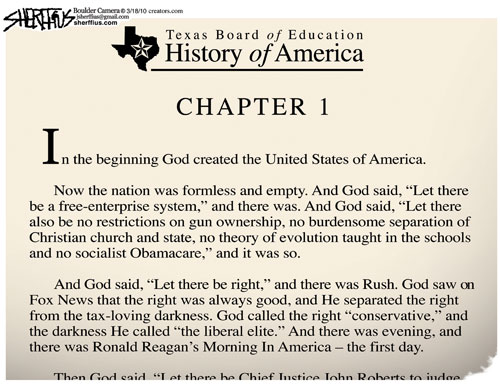

As much as I’m committed to progressive photojournalism, I have to like this cover from the Onion:

The nice touch of imitating the New York Times Sunday Magazine only gilds the lily, as the photographic convention being lampooned is used everywhere: glossy magazines, newspaper ads, direct mail, web sites, billboards, photography books, TV documentary trailers, and more. You can donate or you can turn the page, but you can’t avoid seeing the picture.

There actually is a continuing debate among human rights advocates and cultural critics about such rhetorical appeals, and the Onion cover neatly summarizes a number of key arguments. First, the problem of human deprivation is given a human face, but at the cost of reinforcing damaging stereotypes. The poor (and the Third World) are portrayed as essentially dark, passive, weak, simple, and dependent (need I add that images of want usually are of women and children, and often female children?). Second, analysis has been replaced by the direct emotional impact of the visual image, and reasoned commitment by a sentimental appeal. You are asked to help an individual child who seems so close that you could pick him up and hold him, although the money will in fact go through many hands and may make no difference whatsoever in his life. Third, the poster child’s innocence and obvious dependency dissociates charity from any serious attention to structural change, an inattention that often excuses how the US and other affluent nations are also among the causes of the problem. Fourth, the magazine’s tony production values suggest that there is money to be made off of human misery, and even the photographers’ mixed motives are exposed–indeed, are the point of the parody. Fifth, the enduring contrast between deprivation and the affluent world of the magazine audience is all too obvious: $5 per day is not going to set anyone back on this side of the street, and yet mere charity is all that is imaginable, not serious redistribution. Finally (for now, anyway), the audience may experience the perverse pleasure of indulging in feelings of pity about the suffering of others while giving their middle class conscience an easy out. Whether I donated or not, I gave at the magazine, so I can feel sorry for the poor and good about myself–and turn the page.

Actually, there are additional criticisms, and all of them can (and have been) developed in great detail. So why does the debate continue? There will be many reasons, but one is inescapable: the images work. Despite having become highly conventional, images of needy children open purse strings. Furthermore, if the appeal is not effective, no one else is likely to step in and make up the difference. So, damned if you do and damned if you don’t, and most advocates conclude it is better to do than to do nothing.

Other options remain, however, especially for photographers looking for another angle on a problem. Instead of the exceedingly conventional character of the typical humanitarian image, one might want to ponder this photograph:

Of all the images of the Haitian disaster, I find this one to be surprisingly eloquent. And it shouldn’t be: I shows no people, only property, and instead of the close-up that might grab one personally, we have the distant and distancing impersonal perspective of an aerial view. Nor is it an action shot, and there are no dramatic special effects such as smoke and fire. One might think the most likely reaction is simply, “well, at least it’s over, and although there is a lot of damage, it’s only property damage, not lives lost.”

That’s not what I see or feel when caught in this photograph. Somehow it reveals the massive dislocation that remains after a catastrophe–the profound wreckage, disorder, waste, and raw mess that remains. It also reveals that disaster has its own full weight of inertia. Nothing that has been crushed together in that picture can be pulled apart and moved back or out of the way, much less restored to what it was, without labor, effort, work, and much more of the same, just to get back to even. And imagining it being sorted out–or, more likely, bulldozed–starts one thinking about how it got there, and about what ought to be put back and what ought to be built anew but differently. The photo reveals the enormous forces that were involved, and requires that one imagine what the city should be. In short, it demands more than is required to give five bucks to a child (or a photographer). And if people aren’t evident, neither are the denigrating associations that pull people down.

Communication depends on conventions of representation, but it can become trapped in them. As much as humanitarians rightly insist on the value of the individual person, there may nonetheless be times when we don’t need to see another face. Given the scale of the humanitarian disasters now and to come, more thought might be given to how even things can speak.

Onion Magazine cover from issue 45-45, May 2, 2009; photograph from Chile by Natacha Pisarenko/Associated Press.