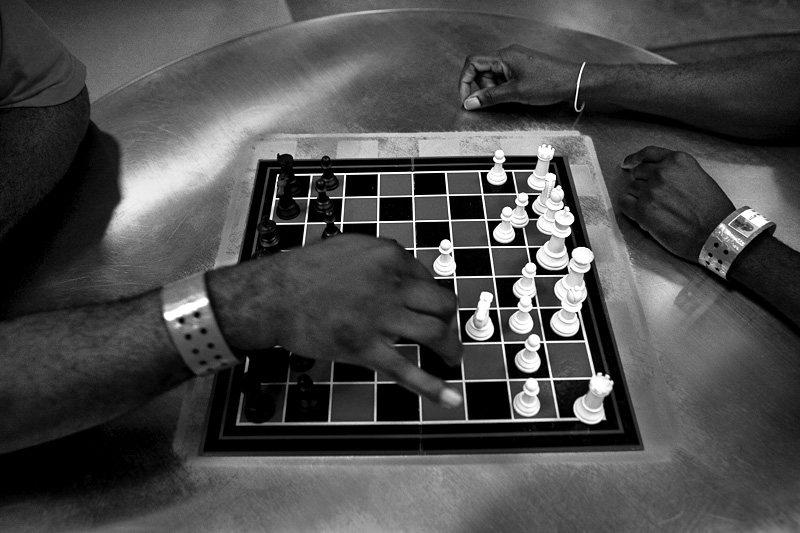

“Locked and Found” is part of Robert Gumpert’s “Take A Picture, Tell a Story” project begun while working on a short documentary concerning the closing of San Francisco’s County Jail 3, the oldest count jail in California at the time. He had the idea of connecting photographs of inmates with whatever story they wanted to tell except for a story of an open case. The project began in 2006 and is regularly updated. To see the archive of photos and to hear the stories click here or on the above photograph of Thaddeus Stevens and Roy Westry taken in August 2009.

Canada, Society of the Spectacle?

Some Americans like to think that Canada is a progressive paradise–not to put too fine a point on it, they imagine Canada as being America without the craziness. You know, a place where you can drive the same car, sans road rage, or have all your favorite TV shows, movies, and music but not have to worry about society amusing itself to death. Canadians strive and shop just like Americans, but still are the soul of decency, tolerance, prudence, civility, and common sense.

Like this:

According to the caption at The Big Picture, “Entertainers dressed as Mounties perform during the closing ceremony of the 2010 Winter Olympics.” So that’s what they are: entertainers. And what about the elephant in the living room, by which I mean the giant Mounty cake? And speaking of Mounties, isn’t that other fine example of the Royal Canadian Mounted Police a Giant Cut-Out? Not just any nation could have mashed up the Rockettes and a Victorian greeting card, but Canada is not just any nation.

I get a kick out of this photograph, which can be read in either direction on the big question of Canadian exceptionalism (just like American exceptionalism, except nicer). On the on hand, we see the same ridiculous, over-the-top, mass pop aesthetics that we have come to expect from Olympic closing ceremonies, Super Bowl halftime shows, and the like. On the other hand, it is still so, well, what you would expect from a nation whose frontier hero was a policeman. That said, I want to side with the craziness and so cut back the myth of Canada the well-mannered America. Face it, they’re nuts, too.

I should quit there, but I there is another point to be made for our academic readers. Guy Debord’s Society of the Spectacle begins with the statement that “The spectacle is not a collection of images; rather, it is a social relation between people that is mediated by images” (paragraph 4). That important point is too easily overlooked, but it also lets Debord off a very big hook: what if a specific image or collection of images suggests a different social relation, or one intertwined with another? And what if Canada is doing the good work of providing a spectacle that can be read in either direction: as the epitome of fetishism and false consciousness aligned with the state, or as something that somehow gets close to that but ends up, well, more negotiable and not so threatening?

Look at this image again, and it’s all there: state power, the commodity fetish, the cult of the copy, separation celebrated, and gender ideology materialized. But more is there as well: in a word, it’s nuts, and obviously so; more important, it is so obviously a theater of duplication that you have to believe irony is in the wings. Excess may not be more of the same but rather one means for living within the spectacle. And come to think of it, perhaps Canada knows a thing or two about being regarded as a copy, but with a difference for the better.

Photograph by Robyn Beck/AFP-Getty Images.

Disasters Natural and Political

Another earthquake, this one 100 times more powerful than the quake that wrecked Haiti. More photographs, although probably less than before due to some combination of better infrastructure in Chile and compassion fatigue in the American media. Comparisons between the two disasters will be made–and sure to include both racist asides and warnings about the Last Days, such are the blessings of free speech. The question remains whether the second quake provides an opportunity to learn something about disasters. Nor is this a question about tectonic plates.

I think this photograph from Pelluhue, some 200 miles southwest of Santiago, is at once typical of the current disaster coverage and yet somewhat distinctive. Typical, in that it documents the nature and extent of the destruction; distinctive, in that the wreckage was done by flooding, a secondary effect of the quake. If nothing else, the photo can prompt one to recognize that this disaster, and every disaster, has more extensive causes and more extensive effects than those seen at the dramatic center of the event.

The photo’s texture may inflect the story further. Instead of the arid, concrete, public, urban environment typically featured in the initial coverage, this rural setting was more lush to begin with and now is awash with the soggy debris of private life. (Yes, those are refrigerators stuck on the strand, and perhaps a buoy for the recreational boating in the area.) It is clear, also, that the disaster has washed up over the land, through no fault of their own, you might say, and that although human domesticity has been disturbed by nature’s excess, a more serene natural world remains, like the horse in the background, awaiting a return to normal activity and dwelling in relative harmony once things are cleaned up and rebuilt. If there is a moral to the story, it is that disasters can have a greater reach than one might expect, but the advice remains the same: be better prepared next time, but get back to normal first. One can almost imagine the scene flowing backwards: the refrigerators moving back into houses, the houses back onto their foundations, the buoy back into the bay, the chairs and buckets back onto the dock, and the flimsy walls of the dockside buildings slapping back together.

Something similar actually will happen, flowing forward, as the aid will come and the investments made and everyone knows what should be the result. Not every disaster zone is so lucky.

This photograph was taken from a helicopter over “a rubble-strewn battlefield” in Marjah, Afghanistan. Note how perfectly, although perhaps inadvertently, the “objective” caption captures the destructiveness so painfully evident in the photo. The three buildings in the picture have effectively ceased to exist, to have ever existed. They are not even mentioned, save to be designated as part of the rubble. (They are another addition to Rubble World, a sector with excellent growth prospects in the 21st century.) As before, the texture of the image speaks powerfully but now with a very different tone: this is sheer desolation, as if the environment had somehow been transformed into war itself, or at least a simulacrum of war suitable for a dark video game. Only one dot of blue remains as the last hint of another purpose for this place of devastation, and soon, if anything is to be done, it will be bulldozed underground.

If anything is to be done. This scene has only the barest trace of a past–shattered concrete without any evident purpose–and virtually no sense of a future. It is a war zone, likely to be leveled for tactical security, and then what? If the armies move on, they leave nothing. If they stay, there is no return to whatever was there before. Likewise, the relationship to other causes and effects remains obscure. The scene was seemingly the center of a battle, but there is no sense of where the war started, why is it there, or where it is going. (This elision of a grand narrative can be a feature of all war photography, as Alan Trachtenberg has noted, but we should add that it may say something about war and have more bite with some wars than others.) War may be more or less destructive than a natural disaster, but only war destroys the future.

There is a political dimension to every natural disaster, but that is not quite my point today. Wars are political disasters, and were we to see them much as we do natural disasters, it might be much easier to help those after the battle and perhaps even to be better prepared to maintain the peace next time. But too often the images of political disasters may, in ways large and small, already be reproducing the damning implication that comes from not being defined as having natural causes. Thus, instead of seeing how calamity has washed over the land through no fault of their own and that there remains only the hard work of rebuilding, the moral of the story is that for those in the wrong place there can be no return to normal life. Earthquakes are episodic, but war and occupation, it seems, are endless.

Photographs by Roberto Candia and Brennan Linsley for the Associated Press.

Cross-posted at BAGnewsNotes.

Sight Gag: The Elephant in the Room

Credit: Nate Beeler, Washington Examiner

Sight Gags” is our weekly nod to the ironic and carnivalesque in a vibrant democratic public culture. We typically will not comment beyond offering an identifying label, leaving the images to “speak” for themselves as much as possible. Of course, we invite you to comment … and to send us images that you think capture the carnival of contemporary democratic public culture.

Photographer's Showcase: On the Outside Looking In

We are pleased to introduce NCN readers to Impact, an exploratory online exhibition site inaugurated by the Resolve collective of photographers and creative professionals and designed to feature the work of independent photographs as they address a common theme or topic. The initial theme is “On the Outside Looking In.” The photograph above is from Sean Gallagher’s “Desertification Unseen.”

The Politics of Anger

If you even saw this photograph you probably didn’t pay much attention to it. After all, it looks like many of the images that have come out of places like Lebanon and Iraq in recent years. One more terrorist, suicide bombing carefully planned and executed by a group of political extremists and religious fanatics. What more is there to say? Nothing, perhaps, until we discover that the explosion is in Austin, Texas, not the war torn Middle East, and it was caused by a lone U.S. citizen who flew a small airplane into a building that housed the IRS as an expression of his rage against corporate profits and the U.S. government in general.

The key thing to notice is how quickly the whole event seems to have slipped from national consciousness despite the sense in which it might be characterized as a small scale 9/11 attack: an airplane flown into a government building, animated by a dissident, vengeful desire to bring the political system down. That’s not the story we got, of course, as most reports focused on the bomber as a deeply disturbed, single individual animated by an inarticulate fury, despite the fact that he left behind a somewhat lengthy political manifesto explaining his long smoldering (and not irrational) anger at what he perceived to be an unjust political system. The above photograph is telling in this regard. Shot with a long lens and tightly cropped around the point of the explosion shortly after impact, the building is consumed by billows of smoke that shroud the intense flames that burn just below the surface awaiting to erupt. It is in its own way a picture of latent affect that serves as an allegory for the predicament of expressing anger in contemporary times: The smoke can serve as a screen to mask the raw affect for a time, but ultimately it is incapable of giving it a productive form or containing it for very long. The result is either dangerously explosive or sheer futility—and sometimes both.

Too often, it seems, we treat anger as an inherently irrational and inchoate expression of political engagement, typically representing it in the roar of an inarticulate mob. But as Aristotle made clear, anger is not madness. Indeed, it is and can be a legitimate and rational political emotion, quite necessary as a motivational resistance to the forces of injustice, and made effective in the careful and deliberate performance of the cultural norms of appropriate social and political recognition. The problem is that in contemporary times we lack useful models for the effective expression and enactment of productive political anger. Either we get the silly rants of groups like the “tea-baggers,” which function as little more than a parody of anger, or we get the truly irrational futility of individuals flying planes into buildings or going on shooting rampages. Neither serves the purposes of a robust democratic public culture.

What we need are exemplars of the performance of political anger that animate the demands for justice and restitution in pointed but measured ways. Where we will find them, it is hard to say, but in the meantime it is important to keep in mind that the political scenarios in which we frame enactments of anger carry a powerful normative force that should never go unmarked as transparent expressions of affect.

Photo Credit: Trey Jones/AP

Diving into Midwinter

The holidays are a distant memory, snow is falling again, and ordinary activity can seem frozen into work and routine. What else is there to do? Days are short, there is too little sunlight, depression lurks amidst the layers of heavy clothing, and just getting about can be a series of chores. One’s options, it seems, are limited.

But don’t tell this woman:

The caption read, “Shenyang, China: A swimmer jumps into icy water at a park.” Really? You’d think the writer had seasonal affective disorder; doesn’t “jump” suggest suicide? As it is, however, she is not jumping but diving, and instead of going to her death she is throwing herself into life.

The tension between death and life suffuses the photo. The snow shrouded treeline along the field of whiteness could be the frozen shore of the netherworld, and the cold, dark, glassy water seems a catch basin for dead souls–like the shadow solidifying under its surface. But suspended against this there is the incredible vitality of her strong, beautiful body, and even the puff of snow testifies to her quick kick up into the air. And all this for one reason: the amazing shock of slicing into the cold water, the sharp gasp, the radiant fire of skin alive.

In 1872 Christina Rossetti penned a beautiful poem that many encounter as a Christmas hymn. The first verse speaks to anyone regardless of faith–to anyone, that is, who has known winter.

In the bleak midwinter, frosty wind made moan,

Earth stood hard as iron, water like a stone;

Snow had fallen, snow on snow, snow on snow,

In the bleak midwinter, long ago.

There is more than one kind of winter. Too much in American national life at the moment seems locked into bleak patterns of dysfunction and stasis. Too many people are hoping to settle for what is safest, and too many are resigned to simply making do or getting by. Who can blame them? When leaders are abdicating right and left and the future looks bleak, it makes sense to pull the blanket close around yourself and not take any risks.

Stuck in the middle of winter, perhaps one should simply wait for spring. I’d like to think, however, that somehow each of us could take the plunge into a better life. This might mean nothing more than doing something unexpected or otherwise out of season. Who knows how much that could change?

Photograph from Reuters.

Sight Gag: "And the Good News is …"

Credit: Kirk Walters, The Toledo Blade

Sight Gags” is our weekly nod to the ironic and carnivalesque in a vibrant democratic public culture. We typically will not comment beyond offering an identifying label, leaving the images to “speak” for themselves as much as possible. Of course, we invite you to comment … and to send us images that you think capture the carnival of contemporary democratic public culture.

World Press Photo Awards

The 2010 World Press Photo Awards were announced last week.

You can see the photographs here.

You may have seen some of the photographs before, as when we posted on this image and The Practice of Domination in Everyday Life. There are many others, however, and many that are likely to amaze. Some also will raise questions about who should be the photographic subject, what should count as an artistic image, and how spectators should respond to eloquent images of suffering. If photojournalism is to remain a public art, we will need both the photographs and an engaged audience capable of debating these issues and more.

Photograph by Rina Castelnuovo/The New York Times.

Haiti After the Catastrophe: The Power of Ordinary Life

This week the New York Times ran a story entitled Haiti Emerges From Its Shock, and Tears Roll. The government had declared a national period of mourning, and the point of the story was that Haitians finally were able to grieve openly and collectively about their devastating losses. An accompanying slide show featured funerals and memorial services, while the story itself included eloquent testimonials that could have been included in any eulogy.

Whatever the good intentions behind the reportage, I can’t help but think that this and similar stories are themselves ritual events: specifically, memorial services provided precisely so that the American audience can psychologically declare an end to the disaster and move on. The massive mobilization of charitable giving is slowing down, and the surge of compassion is being replaced by the daunting complexity of managing the long effort of reconstruction, and, well, it’s been more than a month and the Winter Olympics are on.

Like any story, it seems that catastrophes ought to have a beginning, a middle, and an end. Likewise, the dramatic rupture of the beginning culminates in the symbolic repair provided by ritual performance at the end. And so it is that the shock of the initial trauma is soothed by the tears of emotional release during the time to mourn. These are important features of human life, and the press would be remiss in ignoring them. That said, there is another story to be told that has nothing to do with dramatic gestures.

This is a photograph from the middle period of the disaster–a time when people already were beginning to get on with their lives. Furniture from a ruined house has been put out in the street. A woman is walking by, then stops and checks her reflection in the mirror. You can see that she is adjusting something–her hair or an eyebrow, perhaps. The scene is surprisingly intimate, and our gaze is not intrusive as she clearly would be aware that she is in a public setting. Come to think of it, people often steal a moment of privacy to check their appearance in store windows or other public mirrors, much as she is doing here.

One might be tempted to fault her. “How vain! What a princess. Doesn’t she know her country has been wrecked?” I don’t see it that way. Instead, I see an act of triumph over adversity. A small act, to be sure–we are at the lowest level of the micro-political here–but an assertion that life as she knew it will go on somehow and she has a future in which it matters how she looks. In short, amidst near complete disruption of the normal state of things (where one’s bedroom now is in the street), there remain practical opportunities to do what you would want to do anyway.

I think this ability to assert the small routines of everyday life is an important political resource. And just to make sure that we understand how much resilience is at stake, look at this:

A woman is sweeping up the debris in the street in front of a pile of decomposing bodies. From her smock and broom, I’d say she’s swept up before. And why not now? She can’t move the bodies by herself, but she can sweep, and that has to be done if the place is to get back to normal. And don’t tell her that the scale of destruction is too great or that recovery will take many years or that there’s nothing she can do.

As in the first photo, we see a lone individual engaging in what is usually a private activity, but now in a public space or a space having unusual public significance. In each case, I think we are seeing a civic practice, albeit in a peculiar sense. These are not the practices of state action or global mobilization by state and non-governmental organizations; instead, they are the simple habits of vernacular life. Habits that have transformative power precisely because they aspire to no more than continuity.

Photographs by Ruth Fremson and Damon Winter for the New York Times.

Cross-posted at BAGnewsNotes.