It wasn’t but a few weeks ago when the ballyhoo in the US was that the congressional elections this fall were going to be determined by the economy. Unless the rate of recovery improved, and particularly with regard to the critical variable of unemployment, the Democratic majority was sure to be doomed. Such conventional wisdom can’t be entirely mistaken, because discontent can drive people to vote for change, but now that the election is approaching the tea leaves are turning a bit muddy. One reason, of course, is that the airwaves are full of ads about everything but economic policy. Such reticence is not surprising: the Democrats don’t have a lot to crow about–it’s hard to get excited about saying that things could have been worse–and the Republicans have the even bigger problem of wanting to restore the very policies that created the disaster in the first place. The result is that we are treated to discussions of Sharia law, the right to carry a concealed weapon while you are drinking in a bar, and whether Social Security is constitutional. (As for the latter, no, that’s why you have slaves.)

I don’t want to disregard the more obvious explanations for the continuing dysfunction in American public discourse today, but let me suggest another, overlapping reason for the difficulty that the US seems to have when it comes to thinking about the economy. That reason, as I’ve suggested before, is that too many people don’t think of themselves as workers and of workers as labor, and their distorted conception of themselves is reinforced daily by the images of work that do circulate. Stated otherwise, neoliberal fantasies about the economy now dominate not only government policy but also the conventions of representation that we rely on to think about the economy.

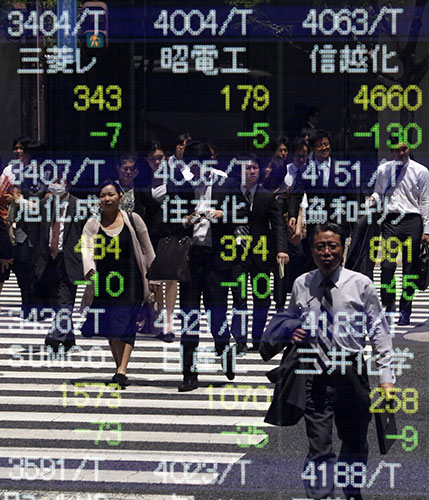

The photograph above is a convenient example of what I have in mind. This week the Dow Jones climbed back above 11,000-good news, right? Well, yes, except that it did so after the announcement that 95,000 jobs were lost in September. This troubling relationship between corporate profits and unemployment is captured neatly in the photograph of Japanese white-collar workers seen through a scrim of stock market data. On the one hand, the photo seems to depict that labor and stock prices are indivisible parts of the same economic whole. For there to be profits, there have to be workers; for there to be workers, there have to be profits. On the other hand, the photo could also reveal how labor and finance are not coordinate, and how the electronic data flows of the stock market are obscuring, displacing, literally writing over the body of labor. Despite the many workers massed to cross the street, they are becoming invisible beneath the numbers, spread sheets, and abstractions that have become, not merely representations of productive work, but their own reality.

There will always be work, of course; the question is whether it will be seen, recognized, and rewarded. That’s why I like this photo.

These are workers–and perhaps one customer–at a German Octoberfest. Needless to say, the photo is a bit different from the typical images of happy waitresses serving tall steins to happy customers. Here, the waitresses are on break–a couple of smokes, a phone call, a text message. These last details are informative: although still a part of the global data sphere, the ratio of bodies to electronic display has been reversed. This is a place of actual work. Another reason we know that is because there is nothing romanticized about it. Unlike the smiling faces and effortless activity seen in ads, here we understand that working people can be bored, tired, and having to manage the rest of their lives around the edges of their work, which is tightly scheduled and often includes having to deal with people, like the kid on the left, who are not exactly at their best.

And even if this photograph shows labor, the workers are still back stage, caught in an unguarded moment that might not be subject to company surveillance and proprietary control. In the US, anyway, we’re not accustomed to looking at work in public, and not at all comfortable–the word should be “competent”–at talking about labor. Until workers can have their rightful place in the pictures that animate public discussion, the results on the ground are going to continue to be grim.

Photographs by Kim Kyung-Hoon/Reuters and Matthias Schrader/Associated Press.