Aerial photos were a big deal back in the day, but they had lost their cachet well before Google Earth and Google Maps came along. Now the aerial photo lies in the odd fissure between a novelty item and the technologies for navigating of everyday life. Until, that is, someone thinks to make it an instrument for social thought.

This photograph by Christoph Gielen of a Phoenix-area retirement community is one of several you can see in a slide show at the New York Times Opinionator blog. The accompanying post by Gielen and Geoff Manaugh provides relevant commentary, including an apt reference to Thomas Pynchon’s The Crying of Lot 49, in which a grid of tract houses is compared to a circuit board. That’s Pynchon doing what he does so well, and it’s also an example of the rhetorical figures of metaphor and synecdoche. Metaphor is a comparison to suggest identity, and synecdoche identifies part-whole relationships. They can work together powerfully by fusing microscopic and macroscopic perspectives, as when one sees the world in a grain of sand, or a galaxy as a piece of jewelry. (The Greek word kosmos meant, revealingly, both universe and ornament.) Both come into play above in the photograph above if you see, perhaps, a hieroglyph, as Gielen and Manaugh do, or the nosecone of a rocket, or a colony in outer space.

In looking at the photo, we always can stay with a literal transcription of the suburban infrastucture of houses, streets, and arterials, and, with that, an analysis of land use, population density, and other administrative variables. Or, without loss of the more pragmatic perspective, we also might let the image work through our imaginations. Not for mere flights of fancy, but to encounter wider perspectives toward the same end of living well collectively.

As I see the suburban development morphing into a space colony, I become aware of the dreams underlying suburban American development–dreams of escape, adventure, self-sufficiency, and community in the desert–and also of vulnerability, hidden dependencies, problems with environmental and social sustainability, and other dangers that cannot be paved over forever. The suburbs, like the American West, always were about colonization one way or another. If images such as the one above can help us see how the burbs, like the cities they encircle, are as amazing and as precarious as an outpost on a distant planet, that is an artistic achievement.

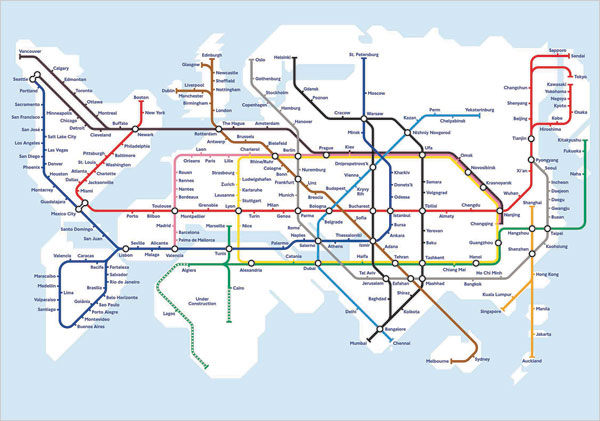

To get the most out of thinking with visual tropes, you have to look for inversions of whatever figures you might have before you. For example, instead of extending a small suburban development into deep space, you might imagine the entire planet as a single city.

This delightful image is from Transit Maps of the World, by Mark Ovenden and Mike Ashworth. The more I look at it, the more possible it seems. Not boring tunnels under the oceans, but living together, all of us, through sensible, sustainable use of public infrastructure. Living in a time, perhaps not too distant, when such ideas wouldn’t make people wonder, “What planet are you from?”

Photograph by Christoph Gielen. The map also can be seen in Strange Maps: An Atlas of Cartographic Curiosities, by Frank Jacobs.

Update: Since I wrote this post, Alan Taylor as put up a terrific example of aerial analysis at The Big Picture.