Credit: John Sherffius, Boulder Daily Camera.

Credit: John Sherffius, Boulder Daily Camera.

Sight Gag: Exit Strategy

Credit: Richard Bartholomew, Artizans.com

Sight Gags” is our weekly nod to the ironic and carnivalesque in a vibrant democratic public culture. We typically will not comment beyond offering an identifying label, leaving the images to “speak” for themselves as much as possible. Of course, we invite you to comment … and to send us images that you think capture the carnival of contemporary democratic public culture.

Photographer's Showcase: A Sense of Place

Today NCN features work by Kay Westhues, who is documenting how rural history and traditions are interpreted and transformed in the present. I encountered Kay’s work at the Evanston cultural center this past weekend, and was immediately struck by how she is able to show both the devastation and dignity of rural life. People who are suffering catastrophic economic and civil decline often have little choice but to cling to patriotic and religious symbols–even as they are being largely abandoned by state and church alike. Kay captures that predicament without condescension or mockery, and she seems to understand how people find a way to live within tattered legacies. This is a portrait of the people at the bottom of the Real America, people who might be in the Tea Party if they were even that well off.

You can see the rest of the exhibition here.

Kay lives in South Bend Indiana, where she and her partner, artist Jake Webster, run a small gallery and performance space called Artpost. She is currently working on a photo project about old artesian wells in the Midwest and the people who visit them; the project explores how these vestiges of the public commons continue to have meaning in contemporary rural life. More information is available at her website.

When Suffering Isn't Shared

New York Times columnist David Brooks cheerily announced yesterday that nation building works. Specifically, that the $53 billion spent to reconstruct Iraq is going quite well, thank you. Not surprisingly, Brooks led with economic indicators, quoting the IMF on the country’s progress since 2003. (Gee, we might ask, what happened in 2003?) He then added for good measure statistics on oil production, cell phone ownership, and the like. To be fair, he did acknowledge that trash removal still leaves something to be desired. Generally, however, it seems that what is good for business is good for Iraq, and that the past can safely be forgotten.

Out of sight, out of mind, unless you lost your son to the sectarian violence unleashed by the US occupation. To be fair to the Times, they presented the other side eloquently with this front page photograph and an accompanying story on the painful search for those victims still lying in unmarked graves. Other stories have chronicled how the reconstruction funds were squandered by mismanagement, corruption and waste, how the country’s civil infrastructure remains devastated, how the security and political arrangements remain tenuous at best, and how military insurgency is on the rise again. Brooks, however, must not read the Times. In his account, there is no memory that reconstruction was needed because the country had been wreaked by the US invasion and occupation (and before that, another war and a decade-long blockade). His most unconscionable oversight, however, is to deny the permanent human damage caused by the invasion.

Brooks allows that “the Iraqi mind has not caught up with the Iraqi opportunity” and then faults their lack of social trust. Besides hitting a high mark for hypocritical condescension, this argument makes light of the human heart and its most intimate bonds. (You’d think a conservative writer would care more about families and communities than market opportunities.) Worse yet, perhaps, by wrapping oneself in the discourse of national development and aggregate economic data, one forecloses on an opportunity for human sympathy. As Adam Smith knew, sympathy is crucial for extension of the self beyond egotism, naturalized greed, and unwitting immorality. It is the stuff of human community.

And that is why we are fortunate to have this photograph from the cemetery in Najaf, Iraq. Having finally located the grave site of her son who was abducted and murdered five years ago, Hassna Mirza grieves. What else can she do? She is plopped down on the ground like an old dog, disconsolate, body shrouded, legs and hands inert, mouth open in a long wail as if grief were running through her, as if grief and gravity were one. Other graves, some marked and some unmarked, extend in all directions to the horizon, as if she now resided in a perpetual city of mourning. The omnipresent sand has covered everything, ashes to ashes and dust to dust, as if blanketing identity and memory alike with the pale uniformity of inanimate oblivion. All that remains, for the moment, is her pain, weighing her down but also bonding her to her beloved.

And tying her to us, if we are willing to admit to the deep, tragic, painful connections between her world and ours. The invasion of Iraq has caused untold suffering in the both the US and Iraq, and no amount of economic development and nation building can undo that damage. Nor is this a matter of finally making right. If we can’t accept a common history of pain, we diminish ourselves. Perhaps this is another case of why nation building has to start at home.

Photograph by Moises Saman/New York Times. For an example of how public discourse can acknowledge two nations united by “shared suffering,” see the remarks by William Jefferson Clinton at the University of Hanoi, Vietnam, November 17, 2000 (Weekly Compilation of Presidential Documents,vol. 46, no. 36, 2887-91).

Cross-posted at BAGnewsNotes.

Icons, Leaders, and Glen Beck

Now that Tea Party rallies have become “non-political” and dedicated to the vague ideal of restoring honor, perhaps the US media can get on with the business of covering what we might call the Real Government–you know, the one that makes laws, distributes resources, provides services, and generally is tasked with protecting the general welfare. The Tea Party will be a footnote to history soon enough–no, not soon enough, but soon–and thus the weekend’s march on Washington provides a fitting moment for reflecting on political movements and their leadership.

![]()

According to the caption at the New York Times, this is a photograph of Glen Beck waiting backstage with security personnel. The photo also is a critical study in American propaganda. The center of the photograph is dominated not by any political actor but rather by a symbol: the Washington Monument celebrates both the nation’s first president and the Enlightenment rationality that his generation of political leaders valued so highly. Austere, abstract, and not in any way religious (unless you count the Egyptian allusion), the monument perfectly captures both aspiration and stability as they are to be deep virtues of a federal government.

That is not to say that the monument shouldn’t serve as a rallying point for populist movements lead by demagogues preaching about “faith.” The monument does set the key for the photograph, however, one that is developed further by the framed images left and right. Abraham Lincoln is Washington’s equal in the pantheon of great leaders, and the figure who guided the nation through its second great crisis. The Native American figure is apparently emblematic of natural nobility and honor–and perhaps of the honor of the Lost Cause now neatly brushed clean of slavery and Jim Crow lynchings. In any case, it is clear that he is a warrior and perhaps a leader of his people. Thus, you have three symbols of leadership on behalf of the nation: a triptych binding together the founding, the second founding, and those who were displaced, all supposedly united by–I hate to say it–a native sense of honor.

And then there is Glen Beck with his guards. Perhaps we are to believe that dark suits and sunglasses are the latest incarnation of the warrior spirit, but the photograph is much more a depiction of contrasts than continuity. Today’s political actors are dwarfed by the images of their forebears, and the supposed unity of the neatly balanced composition belies the tensions between the founding of the union, its being rent apart by slavery, and its reunification including the conquest and near eradication of the original peoples.

Most important, the symbols are inert, objects for manipulation. And that is what the political actor of the day is all about: manipulating symbols and, through them, crowds. And manipulating those symbols without any regard to the original history, commitments, or sacrifices of the real men and women who built the nation or suffered the often tragic turns of its making. (One might note that both suffering and victory were eloquently joined in the original March on Washington, to which Beck’s rally was the “accidental” and parodic sequel.) Indeed, the leader of this rally has rewritten the record book for those who trammel history, which one can do when leading consists in no more than giving speeches without ever having to govern. And when the leader is far removed from his audience, a crowd that is visible only in the distance as a staged source of applause across the moat formed by the reflecting pool.

There is one more contrast built into the photograph, albeit one that requires a bit of history. Construction of the Washington Monument began in 1848 but wasn’t finished until 1884. One reason for the delay was that the project was hijacked by the Know-Nothings, the nativist reactionaries of the day who were precursors to the Tea Party movement. Know-Nothings were virulently opposed to immigration from Ireland and Germany–immigration by people with names like Beck, for example. They also thought that Catholics couldn’t be good citizens in a democracy, wanted Bible readings in the public schools, and otherwise endorsed positions that, with the change of a name or two, are all too common among those gathered on the Mall last Saturday.

Fortunately, the Know-Nothings became a footnote to history, and the monument was completed. Perhaps we could do worse than to have our symbols outlast those who now would speak in their name.

Photograph by Brendan Smialowski for the New York Times.

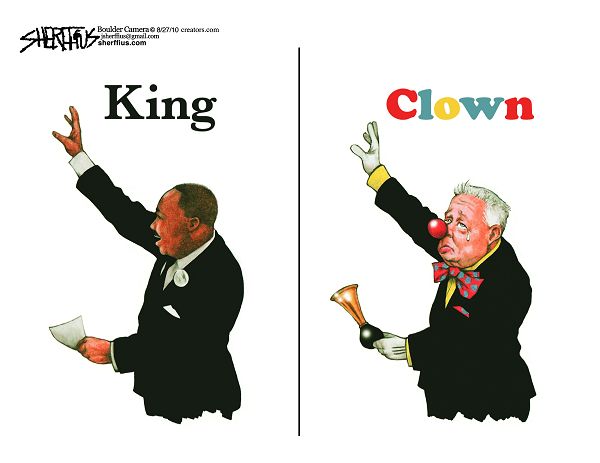

Sight Gag: Of Dreams and Nightmares

Credit: John Sherfius, Boulder Camera

Sight Gags” is our weekly nod to the ironic and carnivalesque in a vibrant democratic public culture. We typically will not comment beyond offering an identifying label, leaving the images to “speak” for themselves as much as possible. Of course, we invite you to comment … and to send us images that you think capture the carnival of contemporary democratic public culture.

Katrina: The Long Aftermath

In recognition of the 5th anniversary of Hurricane Katrina’s landfall on the Gulf Coast, Aric Mayer has put together a short film version of his paper “Aesthetics of Catastrophe” (Public Culture 20:2), in which he explores some of the problems and possibilities in covering the immediate aftermath of the storm.

The anniversary will be recognized by a number of other documentaries, but I doubt that serious reflection on Katrina could do better than to start with Aric’s visual essay. And while it is true that substantial investments have been made in respect to civil engineering, I think it is safe to say that much remains to be learned: about what the disaster exposed in American society and government, about that society’s relationship to nature, and, perhaps most important, about the nature of catastrophe itself. Catastrophe involves not only dramatic destruction but also long, slow processes of denial both before and after the event. Hence the double tragedy when the aftermath is defined by the restoration of the same rather than genuine renewal. Aric’s mediation on the first days of the aftermath of Katrina provides a remarkable demonstration of how a natural disaster challenges not only civil engineering but also the civic imagination.

Aric was the principal photographer working for the Wall Street Journal in New Orleans in the weeks after the storm. His solo exhibition of the photographs, titled “Balance + Disorder: Hurricane Katrina and the Photographic Landscape,” was held at Gallery Bienvenu in New Orleans.

You can see the film here, as one of the posts at Aric’s blog.

Photograph by Aric Mayer, Port Sulphur, LA (southern Plaquemines Parish).

Disposable Lives

One of the little noted features of modern life is how safe many people are much of the time. For all of the warnings about being out too late or going into the wrong side of town, most of us take for granted that we can be out and about on our own most of the time, that we don’t need to carry weapons, that the night will be well lighted, that it is more important to watch out for traffic than for enemies, and that stray bullets are not a problem. There have been many times and places in human history where one could not feel so safe so much of the time. Today, however, many people can afford to have other worries. But not everyone.

In some parts of the world today, violence is a terrible, chronic condition of everyday life. Eastern Congo continues to be the rape capital of the world, while terror bombings and gang killings are ubiquitous in far too many locales. Venezuela has a higher murder rate than Iraq. The Mexican drug wars are getting worse. In the US, homicide is the leading cause of death for young black men. And most of this carnage seems to be no part of ordinary life elsewhere. Even when violence does erupt, it quickly disappears again, leaving barely a trace.

This photograph from New York City provides strange testimony to both the presence and the elusiveness of violence. The blue rubber glove is all that the medical and forensic teams have left behind in the aftermath of a shooting at East 132 Street in Manhattan. (If you look carefully, you can see the yellow crime scene tape on the ground behind the police car, soon to be taken up but for the moment almost as natural and well ordered as the yellow lane divider that it crosses to make a square framing the lone glove.) That glove will have been pulled on by practiced hands and then discarded as the body was wrapped up and sent on its way to hospital or morgue, the evidence bagged up, the questions asked and reports filed. Experienced professionals will have followed well-honed procedures, and in little time the scene will have been returned to normal.

Or what passes for normal. One reason the image is disquieting is that the blue plastic is so artificial and out of place, and yet as one imagines it being picked up (and I think that is implicit in the viewpoint), the street is not improved so much as made disturbingly empty. One then can imagine that you are seeing the street as it would look to someone laying on the ground, say, while bleeding to death from a gunshot wound. At a distance on each side there are trees, nice cars, decent apartments, signs of the good life in a well-ordered city, but up close only the hard concrete leading past the cop car to an empty sky. And once that glove is picked up, there will no longer be any trace of all that was lost there.

The glove can be discarded, forgotten, and then thrown in the trash because it is disposable. Cheap (or not so cheap) plastic gloves are a sanitary precaution, of course, and disposables are just the thing for keeping first responders properly equipped during a busy night. The glove’s brief double duty as a witness to violence will not have been part of the plan, and it is all the more revealing for that. This small object is one example of the normalization of violence–of how a society manages violence and restores a semblance of order (and a large measure of amnesia) rather than confronting what has become a chronic social problem.

This is not to fault the first responders or to pretend that the police aren’t dedicated to and effective at preventing violence. Indeed, violent crime has in fact decreased overall in many cities over the past decades, albeit while becoming horribly concentrated in some neighborhoods and correlating highly with economic decline. At the end of the day, however, one can’t help but think that more than the glove has become disposable. Too many lives are being thrown away, too many neighborhoods abandoned, and, perhaps most important, a sense of shared obligation across all of the city and all of the globe, rich and poor, safe and unsafe, has been lost.

Photograph by Angel Franco/New York Times.

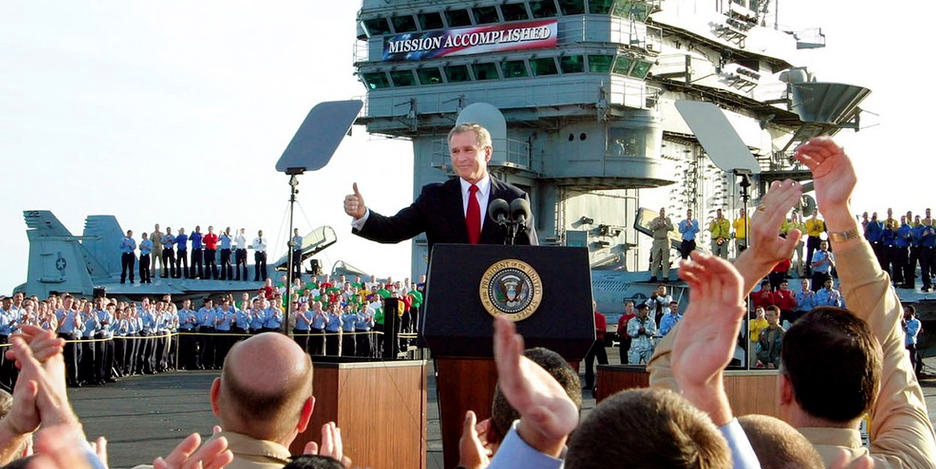

The Mourning After

The war began officially on March 19, 2003, and 43 days later President Bush declared “Mission Accomplished” after landing a S3B Viking “Navy One” aircraft on the deck of the USS Abraham Lincoln. That was on May 1, 2003. This past week—7 years, 3 months and 10 days later, to be exact—and with considerably less fanfare—the “combat phase” of the war came to an end as the last of 30,000 America’s combat troops crossed the border from Iraq to Kuwait en route to the USA. I might feel slightly better about this if we were not leaving 50,000 “non-combat troops” behind to lend “technical assistance” to the Iraqis, a fact compounded by the lingering memory that the war in Vietnam was fought with “military advisers.” All of that notwithstanding, my first thought was that it would be somewhat churlish to feature the above photograph on this occasion. After all, surely President Bush cannot be responsible for the decisions made by President Obama … can he? But then I recalled that the initial motivation for the invasion of Iraq was to seek out and destroy weapons of mass destruction; weapons, lest we forget, which were never found and were in all likelihood a neoconservative fantasy from the outset. “Mission Accomplished,” indeed.

Bringing any troops home is nevertheless a moment for some celebration, and no doubt in the weeks ahead we will see more than a few photographs of loved ones as they jubilantly reconnect at the end of a gangplank or on the tarmac of an airfield. It is, after all, a convention of war time photography. But as we view these images we have to be sure to see past the immediate burst of joy to the long and extended pain and trauma—both physical and psychic—such soldiers and their families will endure. It is unlikely that such images will be taken or if they are that they will be featured; and even if some are, it is a sure bet that they will not circulate widely or that they will quickly fade from memory as too painful to recall and attend to for very long.

As much as coming home can be a moment of celebration, so too is it in some measure a moment of mourning for those who return. I was struck in this regard by expressions on the faces of soldiers leaving or preparing to leave Iraq. Where one might expect to see joy or relief most images showed men—and it is notable that such images were specifically of men, not women—bearing a serious if not actually somber countenance. The photograph below, appearing in a Washington Post slide is particularly poignant in this regard.

Shot at night and from within the hold of a cargo plane preparing to leave Iraq, the image has a degree of sober familiarity to it. We have seen scenes like this before, though typically the “cargo” being loaded is not a pallet of duffle bags, but rather flag draped coffins. What makes this image particularly eerie is the way in which the workers appear to be mourning the cargo as if this were a burial pall. That is hard to imagine, of course, because it defies our experience. How could one possible mourn the return of cargo which metonymically stands in for the return of the troops? But then why would troops about to return home not exude joy? The problem is that our experience of the war is mediated, and from a distance; not being there it is impossible to know what the troops who were there actually experienced—or what their return to their former “civilized” lives might entail … what and how and why they might mourn.

The photograph above is thus in some ways a reminder of the difficulties that we might all have in adjusting to the return of fellow citizens form the war zone—friends and family and strangers alike. For just as in the image, shot at some distance and at a slightly oblique angle with a wide angle lens, our plight might be to witness but not actually to participate in the performative space of action in any direct way. Put differently, the photograph is perhaps an allegory for the wide range of ways in which war entails mourning. For those who were there and for those who were not. Lest we forget.

Photo Credit: J. Scott Applewhite/AP; Ernesto Londono/Washington Post

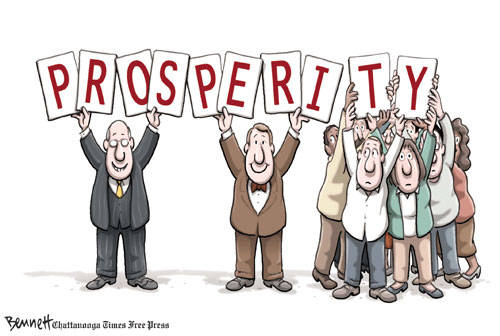

Sight Gag: The Recession is Over (For Some)

Credit: Clay Bennett, Chattanooga Times Free Press

Sight Gags” is our weekly nod to the ironic and carnivalesque in a vibrant democratic public culture. We typically will not comment beyond offering an identifying label, leaving the images to “speak” for themselves as much as possible. Of course, we invite you to comment … and to send us images that you think capture the carnival of contemporary democratic public culture.