By Guest Correspondent J. Daniel Elam

A recent restaurant review in Time Out Delhi described the chicken at a new restaurant as “oily enough to remind us of the Gulf of Mexico.” Too soon? Yes, at least for this temporary ex-pat. But as BP and the US government attempt to ameliorate the environmental catastrophe they’ve caused off the coast of Louisiana, India has only recently seen political progress from its 1984 environmental tragedy in Bhopal.

On the night of 02 December 1984, the Union Carbide India Limited (at that time, a subsidiary of Dow, a US company) pesticide plant in Bhopal, Madhya Pradesh began to leak methyl isocyanate. Over the course of the next twenty-four hours, 500,000 people were exposed to the gas and at least 2,500 died. In the first two weeks following the leak, 8,000 more people died as a direct result; 8,000 deaths since then are believed to be the result of permanently contaminated groundwater and air. 200,000 people have had or continue to have injuries or disabilities related to methyl isocyanate exposure.

This is one of the most famous images of the Bhopal tragedy, taken by photographer Raghu Rai in the days following the leak. It is a baby, blinded by methyl isocyanate exposure (given the weight of the gas, children were the most likely to inhale large quantities of the chemical), mostly buried in one of the mass graves constructed in the emergency following the leak. A hand hovers over its head, perhaps to have one last touch, or perhaps to place a final handful of dirt over the corpse. The picture is horrific and nauseating, grotesque and yet jarringly real. It is nearly impossible to look at the image longer than is required to identify it.

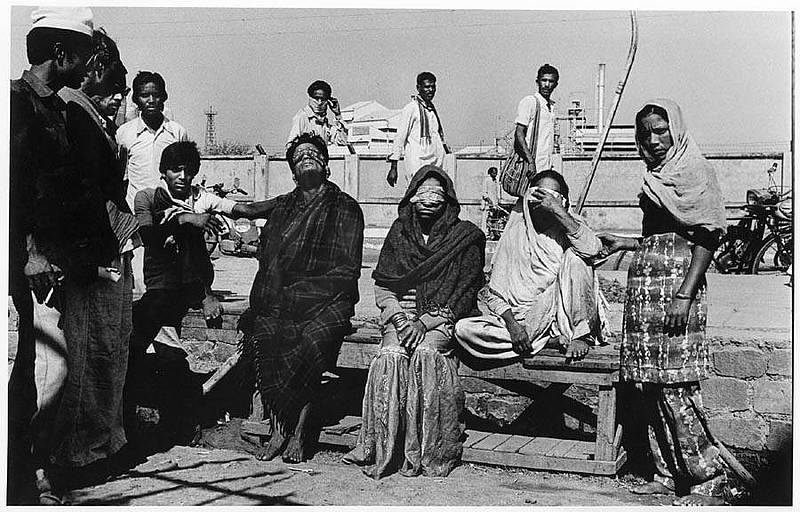

This is another image by Rai, taken on 03 December 1984. Three people sit, blinded, on a bench, framed by people with vision who look with skepticism at Rai and his camera. Most striking, at least to me, is the blinded man, wrapped in a blanket, whose head is tilted toward the sky. His body reads of resigned pain, and although he is unidentified, we can imagine that he died shortly after the photograph was printed (along, most likely, with even the non-disabled people around him). There is something of a Greek tragic chorus in the composition of this photograph, and wailing seems justifiably in order.

What seems most tragic about Bhopal – aside from the lack of prosecution except for seven middle managers made scapegoats in May 2010 – and what makes Rai’s photographs of the event so appropriate, so jarring, is that the effect of gas exposure was (and is) blindness. Thus, Raghu Rai’s photography highlights the uncomfortable difference between the viewer and the subject of the image: sight. That the leak could have been easily prevented (Dow was aware of the plant’s deficiencies), reminds us that oversight is a privilege. Rai’s photography of the Bhopal tragedy reminds us that sight is a privilege–one that may disappear in the span of a few minutes by no doing of our own accord. In witnessing the horrific effects of the pesticide leak, we are reminded of the privilege to do so in the first place, and the responsibility that vision demands we accept.

Photographs by Raghu Rai.

J. Daniel Elam is a graduate student in the program in Rhetoric and Public Culture, Department of Communication Studies, Northwestern University. He can be contacted at j.daniel.elam@gmail.com.