Over 57,000 people attended the recent Shot Show in Las Vegas, the premiere annual gun trade show in the USA. One of the largest and most frequently visited exhibits at the show was sponsored by Glock—the maker of the Glock 19, a 9mm semi-automatic pistol used most recently in the slaughter of 19 people (6 dead, 13 injured) by a deranged Jared Loughner in Tuscon, Arizona. The Glock 19, characterized by the gun maker as “the all around talent,” normally carries a 15 bullet magazine, but for those who think they might need more fire power than that, one can actually purchase 33-shot magazines like the ones used by Loughner. It is hard to imagine why anyone other than the police or military might need such high capacity clips, and perhaps that is one reason why they were prohibited under the 1994 assault weapon ban that was allowed to expire under the Bush administration. That is an issue that should be addressed, to be sure, but there is a different point worth making.

The sponsors of the Shot Show emphasize that the problem is not one of gun control, but rather one of mental health. And at least at one level they are right. I can’t help but to believe that saner gun control—such as a ban on assault weapons—would truly hurt anyone’s 2nd Amendment rights, but beyond that what we really need is more attention to the problem of mental health. But that means a health system attentive to mental health problems and a guarantee of access to that system by those most in need of it. There’s the rub, however, for the people who argue for the unfettered right to own and carry guns in public are also those who tend to argue that “big government” should be eliminated everywhere, and especially and most recently with respect to government efforts to make sure that everyone has access to effective and affordable health care. The shooter in the photo below carries a bag that say’s “Don’t Tread on Me,” and it is surely no coincidence that this is one of the slogans featured not only by the NRA, by members of the “tea party” movement as well.

One obvious response to such an argument is that there is no guarantee that Loughner would have necessarily sought or received the treatment that he needed even if we had affordable access to such health care. That is true enough, though obviously the chances of his getting needed care would have been better rather than worse if it had been easily accessible. At the same time, it is worth noting that Arizona has among the most liberal “carry” laws of any state in the union and that didn’t seem to help the people in Tucson when a madmen began shooting. So where exactly should we be placing our faith in such matters?

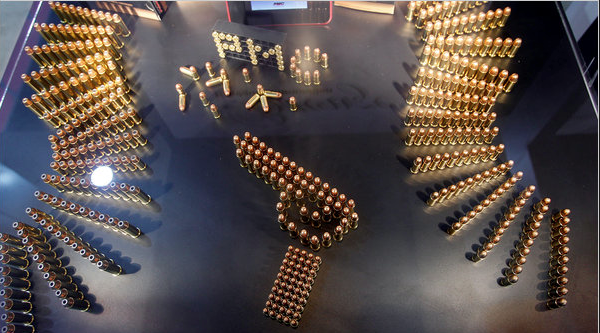

Our concern at NCN is with the relationship between civic and visual culture, and so we should end by looking more closely at the two pictures above featured at a NYT article on the gun show and ask what they show—or, perhaps more to the point, what they almost systematically fail to show. The top image shows what the caption refers to as an “intricate display of ammunition,” but it is of course much more than that. The intricacy of the display animates the tension between minimalist art, as it is built out of so-called “ordinary” and “everyday” materials, and the spectacle of the Las Vegas revue, as the ammo-sculpture is cast in bright lights that accent the golden hue of the uniformly manufactured bullets. The “hand gun” in the middle is shrouded in a slight shadow, but only enough to feature it as somewhat distinct from the ranks of bullets that surround it—as if the featured dancer surrounded by a chorus line—and thus to direct our attention to it as the center of focus.

The second photograph would appear to be different from the first, as it relies upon the aesthetic conventions of realism, and so it is in many ways. But for all of the aesthetic differences, the effect of the two images is the same and it calls attention to the real problem: guns have become objects of desire. And as such, we are witness to a culture that has converted them into something of a fetish; not just as items that evoke a habitual erotic response, though perhaps that too, but as possessing some sort of magical or incantatory power that inspires awe. Guns may be a necessary evil that helps to guarantee freedom, though I’m skeptical of such a claim. But such a fetish should be a warning that something has gone awry; at the least it should be a wakeup call to ask what is not shown—what is hidden or missing?

What is veiled in the pictures above, of course, are the palpable effects that such weapons have upon the world. In a roundabout way it points to our public mental health. And that is a tragedy that knows no bounds.

Photo Credit: Isaac Brekken/New York Times

“It is hard to imagine why anyone other than the police or military might need such high capacity clips.”

Hard perhaps for the author to imagine, but for an imagination fueled by fear and the encroaching “certainty” that “this land” is no longer “our land”, maybe it’s not such a stretch.

Well, I didn’t say “impossible” to imagine. I said “hard” to imagine. And if that imagination is predicated on the “certainty” you describe then I’d say it’s all the more difficult. That’s not to say that some might not see it, but it also doesn’t mean that we should capitulate to it. But as I said above, that’s really a topic for a different discussion. On the other hand, it doesn’t take any imagination at all–since it is pretty clear a fact–to see a society in which mental health care is not being attended to and results in serious and tragic events.

IMO, it’s easy to hard to imagine why anyone other than the police or military if the police or military are potentially those you need to protect yourself from … as, for example, what’s happening in Libya or better yet, the forces fielded by the British in the American Revolution.