By guest correspondent Rachel Rigdon

Despite the Great Recession and the escalating rates of both poverty and economic inequality within the United States, finding images of poor Americans within the news often feels like a process of excavation. There is a curious deficit of photographs of the 44 million Americans living in poverty, and in lieu of using photographs, many articles on welfare or economic inequality feature graphs and charts. One result in a dominant framing of poverty as a purely economic category rather than as a condition of life.

One of the few photos that I have found accompanying an article about poverty is this image from Time Magazine’s blog. Taken at a soup kitchen in Detroit, the focus is primarily on the family sitting at the table in the bottom right of the frame. The background subjects are blurred, creating a sense of a rushed, noisy environment surrounding the family, and yet the large open space of the maroon table offers a small sense of calm. But the photograph also is off-center, tilted, and unfocused, and thus it captures the incongruity of the private, domestic ritual of a family dinner occurring in a public setting. By positioning the viewer slightly above the edge of the table as if about to take a seat, we are invited to imagine poverty as the backdrop of an otherwise normal life.

In response to the limited numbers of photographs of U.S. poverty within the media, a group of photojournalists joined together to create AmericanPoverty.org as a shared space to publicly document the lives of the poor. The website automatically opens with a short slideshow of photographs accompanied by dramatic music and text. Opening with the phrase: “For decades American poverty has been invisible,” it then quickly cycles through several images, mostly of children and families, before pausing on an image of a young, white girl in front of a trailer house. Here text emerges, saying, “It’s not invisible anymore.” The photojournalists’ goal is that by rendering visible what has been invisible, viewers of the photographs will demand social change.

This appeal to potential advocates is present in the choice of photographs for use in the slideshow. All of the photos are of sympathetic subjects such as children and families. Many of the images feature the subject, usually a child, looking directly at the camera as if asking the viewer to see them. These subjects demand a response from the viewer—by virtue of both their embodiment of the large-scale realities of poverty and economic inequality and their identity as equal citizens living unequally.

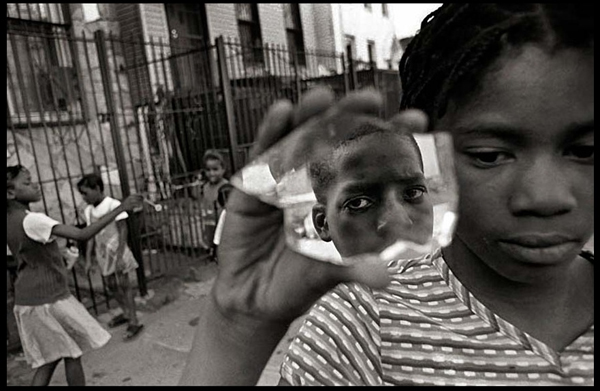

One of the more engaging photographs within the video is this one of several children playing in New York. The primary focus of the photograph is the reflection of the boy in the middle. His face is serious, his eyes intently focused on the reflective surface before him. This use of the mirror mimics the active work of photography by providing an image of a moment that seems to be of reality, while also announcing the existence of the apparatus that can only provide a partial and fractured glance at its subject. The camera’s position is aligned with the boy’s, making what we see within the photograph representative of his viewpoint. The photograph reveals a moment of American life, and our own understanding of it, to be as fractured and incomplete as the boy’s reflection.

In contrast to the boy’s resistant gaze, the girl who holds the mirror is downcast. In the literal sense, she is showing us (the boy, the photographer?) something: a piece of broken mirror. She is also revealing the sad resolve of the boy’s reflection, the proof of poverty’s withering effect on the soul, and the loss of a happier childhood being modeled by the three children playing behind her. The children in the background are playing with bubbles next to a tall, metal fence. The combination of the fragility of the small children and the bubbles with the harshness of the broken mirror and the prison-like connotation of the gate results in a sense of unease. The happier moment playing out in the background seems destined to disappear as the harsher realities of life reveal themselves in ever sharper relief.

Both of these images point to the ways in which poverty transforms the daily activities of life into moments that are both familiar and foreign. They produce a sense of dissonance through the combination of familiar practices with the realities of need. The ritual family dinner becomes displaced by the family trip to the food kitchen; playtime involves bubbles and broken pieces of an automotive mirror. These photographs not only attempt to render visible what is invisible; they also try to render legible the normalcy of poverty. By illustrating scenes of daily, familial life, viewers are encouraged to both identify with their familiarity and be horrified by the inequality they unveil.

Unlike the graphs and diagrams that so often stand in for the visual experience of American poverty, these photographs draw upon powerful values about family life, the protection of children, and our shared sense of horror at their violation. They also challenge the ideology of American exceptionalism and the promise of liberal democracy to provide a high quality of life to all of its citizens. And perhaps this is the real reason that these images and these people remain invisible—they are American yet they trouble our sense of just what that means.

Photographs by Spencer Platt/Getty Images and Brenda Ann Kenneally.

Rachel Rigdon is a graduate student in the program in Rhetoric and Public Culture, Department of Communication Studies, Northwestern University. She can be contacted at rigdon@u.northwestern.edu.

Although there are very few images of the human–rather than statistical–aspects of poverty, the few human images that we see are almost always of African Americans. A critically disproportionate number of African Americans do live in poverty, but it is misleading to use black citizens as a sign for poverty. We are underrepresented in American media, but overrepresented in images of crime and destitution. Both of the above photos feature African Americans; yet other groups suffer our nation’s enormous economic disparities. These two images depict poverty as “urban” and “black.” Images of rural white poverty and Latino agricultural worker poverty and Asian citizens’ sweat shop poverty require an explanation, a caption, a story, a background. Black bodies signify poverty, no need to explore the how or why. Ironically, the AmericanPoverty.org site captions the picture of a “young white girl in front of a trailer” with “(Poverty’s) not invisible anymore.” Hey, look, there are poor white people too! The deep undercurrents of a hegemonic ideology that normalizes African American poverty, yet subtly exceptionalizes white poverty merely repeats and sustains the horrifying inequities. Liberal democracy never promised African Americans OR poor people a high quality of life. In fact, it suggests that they won’t have it. Images such as these merely reinforce the inequities when the photographers “see” black poverty , but “look at” white poverty.

Brenda: Thanks for an excellent addition. No one post can do everything or even say everything the author might want to say, which is why comments such as yours are so important.

Brenda: You are absolutely right that African Americans are disproportionately represented within poverty representations and I myself was troubled by the alignment of the text proclaiming that poverty was visible with the image of the white girl. I wouldn’t go so far as to say that they “merely reinforce the inequities” though. One of the counterbalances might be that both of these images present more sympathetic representations of black citizens in poverty than are commonly seen. By representing families and innocent children, they might be more successful at disrupting dominant narratives about individual responsibility or wealth of opportunity that might be used to indict the subjects for their paucity. It’s difficult to confront the boy’s gaze in the second photograph and accuse him of not working hard enough or squandering America’s vast opportunities.

Another aspect is that by opening with this dramatic slide show, AmericanPoverty.org is attempting to forefront a sympathetic engagement with these subjects that can be activated when looking at the rest of the website, which has much more extensive state-by-state information about the nature of poverty, its victims, and systemic contributing factors (such as lack of public housing or education funding). I’m not arguing that the site completely avoids the problematic lineage of conflating black bodies with poverty. However, by “priming” its visitors to be sympathetic toward the subjects, perhaps AmericanPoverty.org can be more successful at undermining individualistic and racist traditions to representing poverty so that its viewers will get to the part of the site that more explicitly engages with the “how and why” of poverty.

How is producing more of the same thing going to combat the stereotypes that conflate poverty with blackness? I truly don’t understand how showing more picture of poor people of color will hep the existing assumptions made by most Americans and foreigners about African-American class demographics. I do not mean to attack you personally Rachel but your blog post does not help things. You write about the lack of images of poor Americans and illustrate the blog with photographs of only one ethnic-racial group, Black Americans. Could you not find any photographs of poor Asian, Caucasian, Hispanic Americans or were photos of black people just easiest to find?

Your defense of your actions is equally disappointing. The history of photography is chock full of “diverse” images of African-Americans that present sympathetic representations of black citizens. Regardless of the intention of the photograph or your intentionsin using it to accompany your article, the action speaks louder than your words. By action, I mean the fact that despite the fact there are photos of other ethnic- cultural groups that you could have used, you choose to illustrate with photos of poor African-Americans.

“One of the counterbalances might be that both of these images present more sympathetic representations of black citizens in poverty than are commonly seen.” That is a great way to gloss over the fact that Black Americans in this country are the default group when it comes to issues of poverty.

Well-intentioned photos of poor black people? I must look beyond the surfaces of images (poor black people) and situate them in our cultural context to assess underlying messages (poor people are black/black people are poor). People who produced minstrel cartoons brought an underlying ideology of black inferiority to a visual surface; black people were unfit to participate as citizens in a liberal democracy. They were foolish, inept, childlike, unable to care for themselves, mainly concerned with music, food and fun. The message of minstrel images–the work that they did–was not on the surface. There was strong defense of minstrelsy as good, clean, fun–doing no harm. Of course, contemporary images cannot be so blatantly racist, but images of poor black people–worthy of our sympathy–do the same work. Reading how “helpful” these photos were meant to be reminds one of supposedly rational defenses of much older black stereotypes and demeaning images. “Sympathetic images of black citizens in poverty” do not counterbalance the plethora of negative depictions in media. Nor do supposedly sympathetic images make up for the lack of images overall–particularly positive images. Flattering pictures of our photogenic president aside, updated stereotypes are softened with a twenty-first century lens of political correctness and unwanted “sympathy”. The Invisible (American) Family images are part of a continuum of black representations in this country; these representations performed cultural work that the producers could not or would not recognize. The history of black representation, however, compels us to examine how visual media have portrayed African Americans in the past. A helpful site for basic information on black stereotypes is at Ferris State University’s Jim Crow Museum website, http://www.ferris.edu/htmls/news/jimcrow/index.htm. The site provides insight on past and present representations of African Americans. It helps explain the power of individual and collective images, and places them in a cultural context that reveals their persuasive and influential work in our visually oriented society. Images reveal and perform our ideals, which is why they are worthy of our closest attention. To understand the ongoing problematics of African American representations, one must position images such as The Invisible (American) Family photos in a cultural and historical framework.

@Amanda – My point at the beginning of the article was exactly to illustrate the struggle in finding any images of the poor, yet alone those that are as diverse as the individuals who are poor. My use of these two images, specifically the top one, is indicative of the amount of skewed representations in the media: I struggled to find any photographs and when I did, it was, of course, of a black family. I wasn’t just looking for photos “online”–I was looking for specific instances of the media showing something other than a graph, ideally in an article or setting that was more sympathetic than normal. I knew that this was likely to suffer the double bind of reproducing a different and also highly problematic stereotype of black poverty.

Perhaps you are right though about the second photograph. I did have numerous photographs to choose from on AmericanPoverty.org, including several which were not of African-Americans. I didn’t consider that part of my responsibility in covering the media might be to actively work to avoid reproducing those same associations between poverty and black Americans, although I’m still hesitant to accept that this is what is happening in this post. I explain why in my response to Brenda below.

@Brenda – I’m not sure what your alternative is. Should black bodies disappear entirely from the discussion of poverty and economic inequality? I think there is something very concerning about being opposed to any representation of black poverty. It exists, it needs to be seen. Would an artificial lack of photographs of African-American poverty or a larger amount of photographs of more diverse examples of poor individuals lead to a better understanding of poverty? Maybe, but I’m not sure that’s really the central issue.

I called these photographs more “sympathetic” but I don’t necessarily mean that they are all about making us feel badly for the people in the photographs. I’m anxious to avoid terming these photos more “realistic” – rather what I mean is that these images are trying to create a space for us to engage with the individuals in the photographs in a way that allows us to see them not as stereotypical black bodies in poverty, but as individuals, fellow citizens, human beings who have been wronged and to whom we owe some responsibility. That is what makes these photographs different from the minstrel cartoons you cite.

Visual representations of poverty will always have some level of intersectionality with race and, as Bob noted above, I was unable to include it in this post because of space limitations which compelled me to focus on the basic question of visibility implicit in photographs of poverty. Just what this “visibility” means for already hyper-visible poor African-Americans is a central question in my research and I certainly appreciate both of your critiques as I move forward.

Rachel,

Thank you for your well-considered response to a challenging series of posts. As one of the “human beings who have been wronged, and to whom we owe some responsibility” I am not sure if I am one of the “we” or one of the wronged victims. The depth of our ideology reveals itself in our use of language. “Us (or we)” and “them” is one way that “othering” occurs. Of course, there is a difference between late 19th and early 20th century minstrelsy and current, routine depictions of African American poverty. The purpose of the minstrel pictures was to “prove” that African Americans were unable to care for themselves, and incapable of joining our liberal democracy, and I mentioned them as an obvious example of the continuum of black representation. They could not take care of themselves, those minstrels. We had to make sure that we took care of them. Coons, bucks, toms, jezebels and mammies were primitive distortions of real people, of course. The photos you selected are actual pictures of human beings who are poor and black. What might be the purpose of segregated images of poor people? I don’t think it is to prompt a sense of responsibility, or call attention to their victim status in any way that will address the social issues that create diverse poverty in all races. I don’t even know if I would be considered part of “we” or part of “them.” Martin Berger’s excellent new book on the purpose of civil rights images addresses how “we” used those images. In Seeing Through Race, Berger argues that sympathetic images of African Americans served a larger purpose–he addresses a specific contest regarding the purposes of mediated black images: http://www.ucpress.edu/book.php?isbn=9780520268647&utm_source=eNews&utm_campaign=9b49fe6968-Cultural_and_Ethnic_Studies_A_B_test_May_2011&utm_medium=email. There is always a purpose when we select images, and I’m glad that your post provided an opportunity to further examine how mediated images of African Americans serve a function, reinforce ideology, and sustain certain notions about race.