Guest post by Lisa Carlton

Literary and visual tropes of homecoming are essential to narrating war. Take, for instance, the timeless Greek war mythology of Homer’s Iliad and Odyssey. Both of these poems invoke the theme of “nostos” or homecoming. Or we might think of the iconic WWII image of the Times Square Kiss. Typically, homecoming tropes signify an end to a time of national conflict and strife—a relative return to normalcy. But the wars of the new millennium are perpetual. They resist narrative’s conventional markers of a beginning, middle, and end.

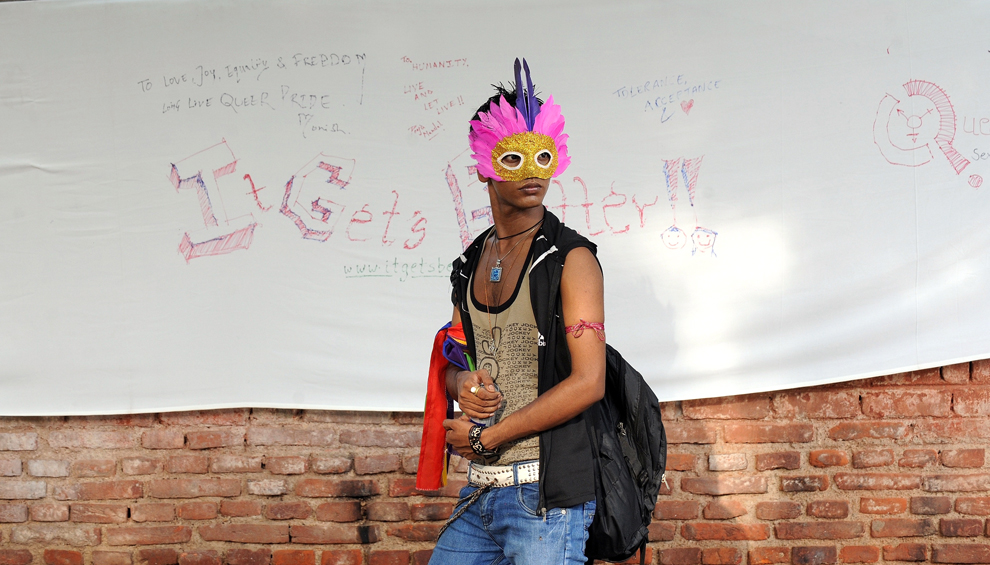

The image above was taken at a homecoming ceremony for the South Dakota Army National Guard’s 196th Maneuver Enhancement Brigade on May 3, 2011. It appeared in the Memorial Day collection of “In Focus,” The Atlantic’s news photography blog. According to the caption, the little boy in the photograph is four-years-old and the little girl is two. This means the boy was born around 2007 and the girl was born in 2009. By then, the war in Afghanistan had been underway for over five years and almost ten. These children were born into a culture where war is the norm.

The uniformed father figure is identified by the caption as Major Jason Kettwig of Milbank, South Dakota. An officer-level rank suggests that Kettwig has been in the Army National Guard for quite some time; Probably before his young children were born. The photograph’s caption explains that this particular “group of approximately 200 soldiers has been serving in Afghanistan for the past year.”

One year ago the little boy in the photograph was three; and the little girl was just one-year-old. In the image her hands lovingly and gracefully cup her father’s neck. She is not clinging to him, as we might expect a young child to do to her father. Instead, her head is pulled back from his. She gazes at his face with a mature, furrowed brow, a look of relief, concern, and wonderment, commonly identified on the faces of adults. She has not seen this face in one year and she appears to be studying it, searching for traces of change since the last time she saw it. It reminds me of the way parents look at their teenaged children after their first long stint away from home. But her father does not return her gaze. He appears to be looking at his son.

The son, who is four-years old, stares off into the distance over his father’s shoulder. His facial expression is less engaged than his sister’s. His lips part and turn upward, but the smile looks almost hesitant. Perhaps he has experienced this homecoming scenario before. Maybe, by his ripe old age of four, he has experienced his father’s deployment and return once already. The boy wears a green tee shirt, almost identical to the color of his father’s desert camouflage. And his short, clean haircut adds to the father-son likeness. As the father looks at his “mini-me,” the reader is invited to wonder if military service is in this little boy’s future. So as the father looks at his son, and the son looks off into the distance, and we, the viewers look at these children, all of the gazing that animates this image is oriented toward the future.

While the children are the most salient figures in this photograph, with their adorable, round faces and the light bouncing off their shiny, sandy blonde hair, the father figure is positioned as central. However, it is the back of his shoulders, neck, and head. We cannot see his face, and as such, we have a harder time identifying emotionally with him. We can only imagine what his face looks like. Does it express happiness? Relief? Melancholy? The back of his head does not provide cues for how we should feel. Perhaps the absence of his visage marks a loss of his humanity while at war, or perhaps it symbolizes an anticipation of his death, or maybe it’s a social commentary on what has been described as a faceless war effort.

The photograph’s composition is an uncanny inverse of Dorthea Lange’s Migrant Mother. Instead of identifying with the mother — or the absent father figure — as we might have with Lange’s image, this photograph turns our attention to the children’s faces for a model of how to feel and how to interpret the action in the scene. This important shift in subjectivity positions the viewer as childlike—an infantile citizen who, like the four-year-old and two-year-old in the photograph, has become a little too acclimated to a culture of perpetual war. When we take on the gaze of the confused and bewildered child, we as citizens are invited to remain complacent and uncritical. Again.

Photo Credit: Eisha Page/Argus

Lisa Carlton is a Ph.d student in Communication Studies at the University of Iowa. She can be contacted via e-mail at lisa-carlton@uiowa.edu.