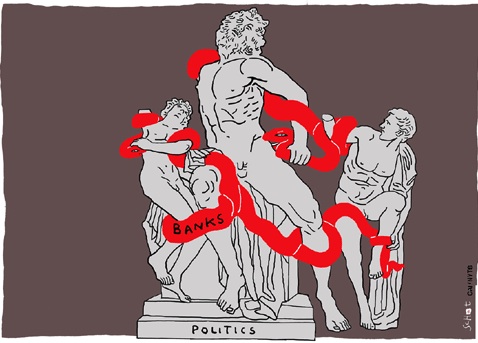

The headline at The Huffington Post screamed “HOLY WAR.” The subhead added “Notre Dame Sues Obama.” And this was the image:

I thought twice about saying anything: as a Huff Post junkie, I have little basis for faulting how they mash up images and stories. Every story gets an image, no matter how distant in space, time, or topic it might be. Some of these visual captions are clever and some are cheap come-ons that work even though I should know better, but what the hell, it’s free, right?

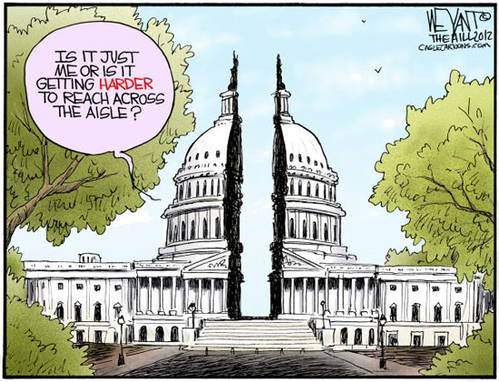

Well, yeah, but “free” usually means that someone else is paying the cost. And in this case, we all lose something, for the mashup does just about all that can be done to misconstrue the issue. Just for starters, the debate over extending health care coverage to include contraception isn’t a holy war, and the lawsuit is addressed to the United States government, not the Obama administration. Nor is Notre Dame bringing the lawsuit by itself; instead, it is one of a number of Roman Catholic organizations listed as plaintiffs. But these distinctions are small change compared to what is being said by the visual juxtaposition of Obama and You Know Who.

If this direct comparison of Obama with Jesus Christ doesn’t play to conservative invective, I don’t know what does. The triumphant Obama stands in the place of Christ, while the movement from left to right suggests temporal succession. Obama wants to replace Jesus, and doing so would replace Christian Civilization–signified by all the lesser figures in the religious image–with a secular society where the right values no longer constrain political power. (This would be the semblance of a rationale behind the references to Obama as a dictator or someone hell bent on dictatorship–claims that are legion on the right and evident in the comments following the story.) Thus, the legislation reflects not a difference of perspective about the scope of federal laws, but a struggle over who shall have the ultimate authority over all: God or this political leader defined solely by his ambition.

There’s even potentially a racist element to the comparison, if you see Obama as imitating Christ rather than acting on his own accord, but I’m not going there. The fact is, it’s bad enough as it is, and not least because it obviously is intentional. This was not what Obama was doing in response to the lawsuit or on the same day–instead, a photo from a campaign rally or political convention has been pulled out of the file precisely because of the iconographic similarity with the Christ figure. And, of course, Obama loses legitimacy no matter how you make the comparison. If he is like Christ, then he still is deficient in virtue: egocentric and awash in hubris instead of self-sacrificing and salvic. And if he is not like Christ, then he has no prerogative to challenge religious authority.

But it gets worse yet. The policy in question is in fact not the directive of a sovereign leader, but rather the result of routine legislative and administrative processes. Likewise, the objections to the policy do not in any way, shape, or form come from Jesus Christ, but rather from the leadership of a religious denomination regarding its own administration of large bureaucratic organizations. And it is not inappropriate to add that said denomination has had plenty of reason of late to question its own claim on moral authority, and that hubris and other abuses of power have been all too evident as well. But you wouldn’t know that from these images.

Those who complain about “the liberal media” would like us to forget that all media are subject to the same vices. Culture wars may be stupid fabrications contrived to mobilize voters for reactionary ideologies, but they also sell papers and keep eyeballs on the screen. Fair enough, as we all have to make a living, but I still wish that the media claiming to represent my interests knew where to draw the line.

(No photo credits are given, as none were provided.)

Cross-posted at BAGnewsNotes.