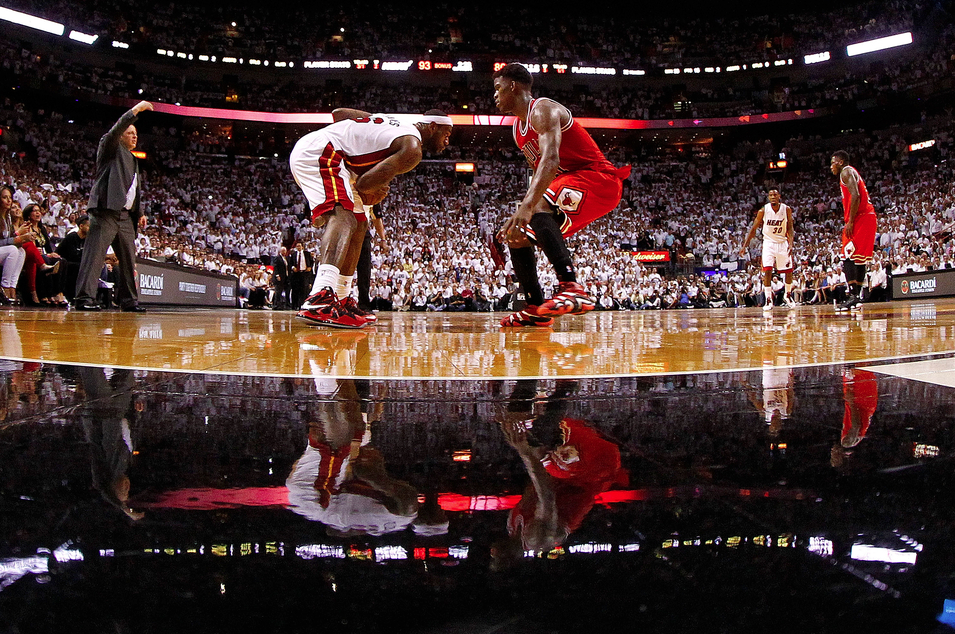

We don’t write about sports very much here at NCN and today will be no different. After all, what is there to say here. The photograph pictures the Miami Heat’s four time MVP LeBron James about to take the Chicago Bulls’ Jimmy Butler to the basket. The only suspense is whether it will be a three point play or not. No, what makes this photograph notable has almost nothing to do with the actual action taking place and everything to do with the way in which the camera has captured two scenes at once—one on top, the “real” scene, and the other, on the bottom, a reflection from the highly polished floor.

Of course, one might argue that this is only one scene, the inverted image on the bottom a natural extension of the top image. And that would be true also. The question, really, is how one wants to “read” the image. We typically think of a mirror reflection as an inverted but otherwise identical (re)presentation of the original. It is one of the reasons we are so often challenged to “look at ourselves” in a mirror, so as to see what is “really” there, or at least what others purport to see But here, while the original and the reflection bear enough points of similarity that one might identify them as the same scene, they are not identical.

The top image is sharp and clear, consonant with the photojournalists avowed dedication to the realist aesthetic that purports a sort of mechanical objectivity—everything to scale, the light natural, the natural plane of the image represented as if one were actually there witnessing it. The bottom image has more of the quality of an impressionist painting, the appearance of thin brush strokes that call attention to texture, especially as it relates to human movement; emphasis on the quality of light as it effects the scene; and finally notice of the unnatural angle that resituates the viewer, underscoring the sense in which what we are looking at is clearly a representation that needs to be decoded and not the thing itself.

The effects of the image and its reflection are different as well. Note, for example, how the realist image locates the contest between James and Butler in a multiplicity of scenes that first calls attention to the game itself as we see the coach calling out orders and other players positioning themselves to respond to the central action, and then calls attention to the immediate crowd watching the event. The focus is clearly on the two principles, but they are part of a larger event. By contrast, the impressionist image focuses our attention almost entirely on the central actors, giving them an almost epic significance, everything else cast with a spectral patina that suggests that they are both there and not there (perhaps like the external viewer of the image).

Whether you see one scene or two either (both) is (are) shot with the same camera, with the same aperture, from the same vantage point, and at the same moment in time. And yet what we see are two potentially and palpably different (albeit related) events, each calling attention to the otherwise taken for granted conventions that underscore both what is present and what is absent in the other and thus animating the possibilities of meaning. What makes the photograph particularly interesting then is how it schools the viewer concerning the everyday necessity of visual literacy, always “reading” an image, not just glancing at it, seeing it for what it always is: an artistic construction.

Photo Credit: Mike Ehrmann/Getty Images

The reflection makes me think of the paintings of LeRoy Neiman. I always considered his work to be dreadful, but now I see how he might have been capturing something that his fans appreciated: a sense of movement and of potential movement and the way each moment of athletic competition can surge in more than one direction in the next instant. These qualities are there in the lived experience of the action, but subdued by the static quality and sharp lines of the photograph. If you turn the image over and look at the reflection as an upright image, they come to fore.