Sometimes you just have to say “No, not really, please tell me you’re not doing that.”

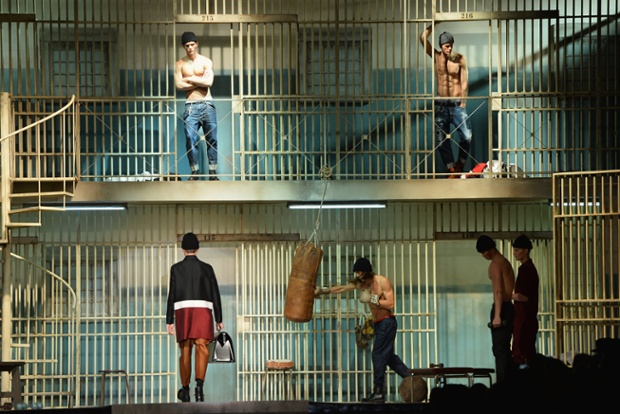

And we all know the answer to that question. In this case, it would come from whoever designed the Dsquared2 show for the Milan Fashion Week Menswear Autumn/Winter 2014 collections. Italian prisons probably are not as bad as those in the US, but still. Are we really seeing fashion models posing as prisoners? Didn’t anyone stop and think that maybe, just maybe, there might be something fundamentally obscene about pretending that prisons are just another place to strut your stuff? Shouldn’t there be some recognition of the difference between affluent excess and stark deprivation, or between one of the more dangerous environments on earth and one of the most privileged?

At this point many people probably would pull back, shrug, and say, “What did you expect? It’s a fashion show. Of course it’s going to be over-the-top idiotic.” I can’t do that, however, because I’ve already written 28 posts at this blog on fashion photography, and worse yet, I’ve argued that it is a weird form of performance art that can provide profound insights and prophetic warnings regarding society and politics. Of course, not every image from fashion week does that–in fact, most of them fall far short–but the question arises of why some displays might be art and others miserable embarrassments.

There is a reliable answer, but we have to take an academic turn to get to it. The key distinction here comes from Biographica Literaria, a book of literary commentary by Samuel Taylor Coleridge. In that work Coleridge distinguished between imagination and fancy. Imagination was the vital ability of the mind to see its way into new perceptions, new creations, new syntheses; it was the human ability to create ideas, images, and relationships that had never existed before, and to do so in a way that brought us closer to the real nature of things. Fancy, by contrast, was merely the mind at play with things it already knew: it was the mechanism by which we assembled and reassembled memories without regard for reality in order to pander to our desires.

To bend the ideas in the direction of photography, we might think of imagination as a way of extraordinary seeing: that is, how one sees beyond the horizon of ordinary observation or conventional belief. Astronomy, for example, is an incredible act of imagination: by looking at a pale disk and points of light in the sky, people came to understand that the earth and the moon are planets–something that couldn’t be seen in any way until just a few decades ago–and that the universe consists of billions of billions of galaxies that will never be visible to the naked eye. Likewise, photography has been a remarkable exercise in imagination, for by showing everyone people, places, events, and things they would never see otherwise, it has brought billions around the globe to realize that they are part of a common humanity living in a myriad of different cultures that no one will actually see together. In both arts, moreover, the mode of extraordinary seeing brought the viewer closer to reality, not farther away from it.

These examples also demonstrate that works of the imagination need not be accessible to everyone, and that they can be misused to very contrary purposes. But we knew that. That important contrast for the moment is with fancy as it is a mode of all too ordinary seeing. The sad truth is that when someone is being fanciful, they also are all too predictable. Fancy is party hats and balloons and drinks on the sly at the office; imagination is the single, mysterious flower waiting for you at your desk.

You get the point, and so back to the big house on the runway. I won’t rule out the possibility that it could have worked, but I know what would have had to happen. A fashion show staging a prison should bring us to see affluent consumer society from inside the prison, or to see how fashion is a form of imprisonment, or how it is an adaptation on behalf of freedom to less coercive forms of imprisonment in ordinary life, or . . . . You get the point, right? Whatever the display, it should not simply take stock fixtures from the prison and stock poses from male modeling and mix them up for fun and profit.

To conclude, as we academics like to say: fashion and fashion photography can be works of the imagination, but they risk being merely fanciful confections. When the subject being appropriated for the show is one involving tragedy, deprivation, humiliation, violence, and everything else that lurks in the dark side of the criminal justice system, it really matters whether we are being brought to see anew or to enjoy habitual blindness.

Which leaves only one question: which side is the photographer on? Does the composition simply feature the bad art before it or call attention to its failure? Does the distance between camera and tableau suggest a similar distance from the reality of the prison, or was he just trying to include all of the set? This isn’t really a question about the actual photographer’s intention, but rather about how you see the image. What do you think: see anything that strikes your fancy?

Photograph by Tullio M. Puglia/Getty Images.

Cross-posted at BagNewsNotes.

Discussion