A frame is always a specification: look here, not there; inside, not outside this space. Photography’s framing of the world seems to be essential to both its success and its liabilities. It allows specific persons, places, things, and events to be seen, and always without most of what surrounds, constrains, qualifies, or otherwise defines them. So it is that captions are thought to be essential: only they can say what lies outside the frame.

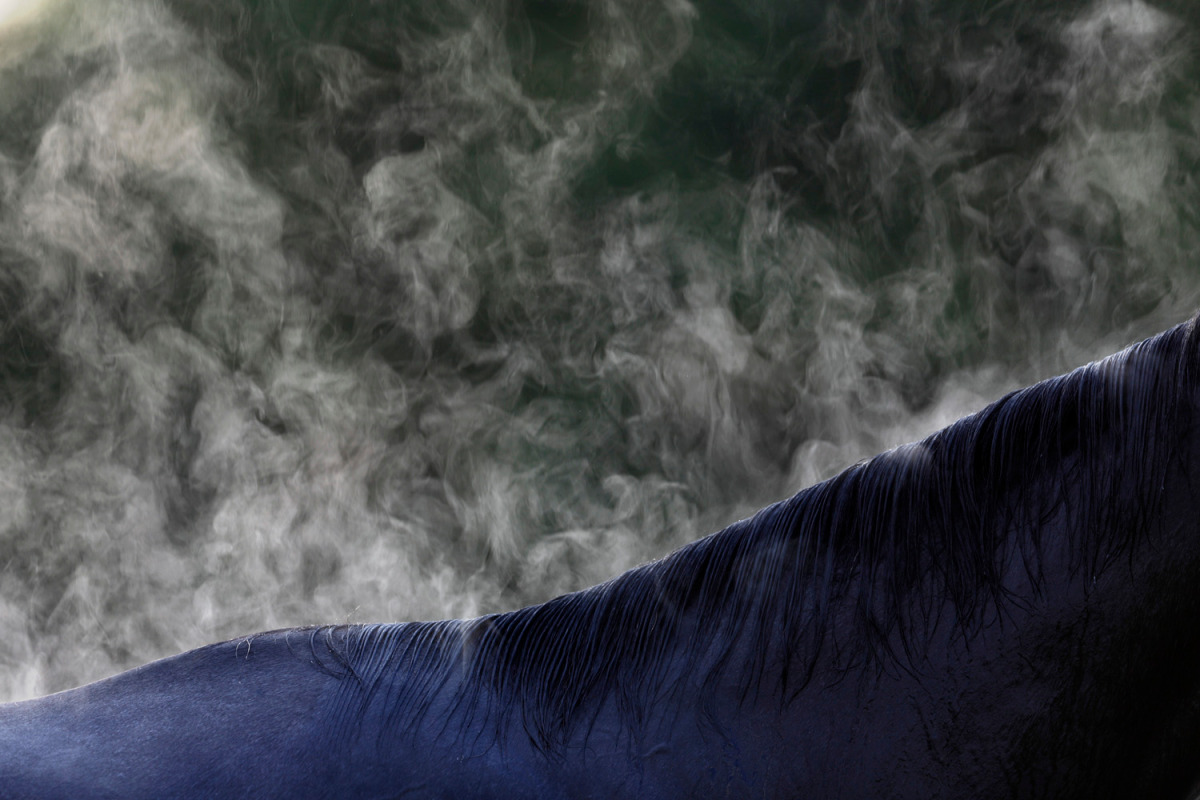

But that doesn’t mean they would tell you much, or that the additional context contributes to perception. Let me suggest that this photo will be diminished, not enhanced once you learn that it is showing steam rising from a thoroughbred horse in Kentucky. That caption has widened the frame, but only to make the image less distinctive, less focused, less intense, and less suggestive. It has displaced what are acutely aesthetic properties, substituting instead a common sense understanding of a routine world. In that world, horses and steam are very familiar things, and things rarely seen without some larger interest controlling perception. What is the temperature? Will he run well today? You might as well ask What’s for lunch? Whatever the answer, it comes with a very wide and very conventional sense of context.

Photographs are so useful in so many settings because of how they provide neatly framed perceptions. “Here, look at this?” can be a very pragmatic and efficient act. The uniformity of the physical framing is an important part of that pragmatism, even as it sets up the medium for easy criticism. (Hint: reality is not prepackaged. Why that isn’t said about painting is beyond me.) What may be under-appreciated is how the framing works in concert with a deep tendency toward formalism. Framing still is tilted toward specificity, but it also can, in some cases, transform perception from being focused on objective subject matter to being attuned to formal patterns.

Patterns, of course, are never merely specific. They generalize. They come from somewhere and extend, if only in the imagination, through continued replication. But to do that, they have to be interrupted. A continuous pattern soon becomes a blank wall, an empty horizon, a long stretch of ground. Hence, the importance of the frame: by cutting off perception, it brings form into view. What remains to be fully explored is how these two elements of all artistic expression combine in photography to create a distinctive capacity for abstraction, or perhaps for something that is no longer merely specific but not quite abstract. Something that may go without saying in language, but that could perhaps have additional power in a visual medium.

If nothing else, photography at least provides a distinctive availability. In the right hands, all you need is an iPhone:

Photographs by Luke Sharrett/Bloomberg via Getty Images and David Sutton/Sutton Studios. For an excellent study of abstraction in fine art photography, see Lyle Rexer, The Edge of Vision: The Rise of Abstraction in Photography (New York: Aperture, 2009).

[…] Frame and Form by Hariman […]