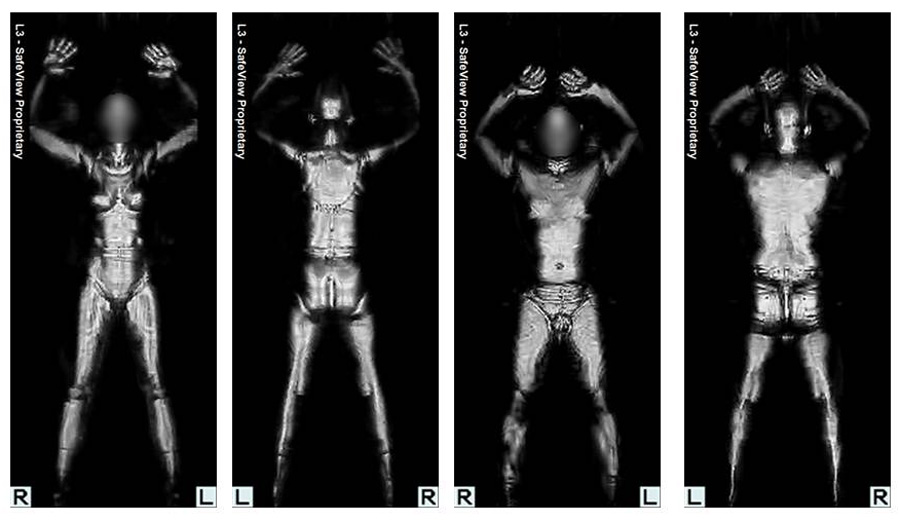

It’s like the day before, and all the days before that: back to business as usual in the war zone.

This photograph of Iraqi war dead is from well before yesterday, but it still has a point to make. I don’t want to make light of the Remembrance Day commemorations around the globe (including the more optimistic variant of Veterans Day in the US). It is right and proper to remember the war dead, to honor all those who served, and to humbly acknowledge the debt owed by those who did not have to make the sacrifices demanded by war.

But that is not all that is needed if we are to confront the ugly face of war in our time.

The photograph above is a sure counterpoint to the solemn, stately, decorous rituals observed yesterday and relayed across the slide shows and other media. In those moments of observance, respect is paid, and war itself is recast as an exemplar of supreme values. The hard facts of loss are made explicit, and the actual carnage is abstracted into flowers, flags, dress uniforms, and the precise discipline of military ceremony. The nation reaffirms itself as a community of memory, and the reality of war is forgotten.

The rest of the year, however, is a different story, and not least in the war zone. I’ve chosen this photograph because of the direct contrast with formal observance. Instead of being treated with dignity, these soldiers are being handled like trash. Yes, they might get a decent burial eventually, but for anyone seeing this phase of the operation, the damage has been done. Civilians, other soldiers, and now you have all been insulted; not to the extent of the dead and their families, but close enough. That reaction is appropriate, because a truth about war has been revealed: it is not in the service of the highest values, because it degrades those values. It destroys lives, communities, and our common humanity. It converts the human world into waste.

Much ink has been spilled about whether photojournalism should expose the bodily horror of war. This photo, like many others in the archive, demonstrate that less can be more: there is little need to see the gore, because more than physical destruction is at stake. If you do want to get closer to the mutilation that troops in the field have to experience, you can search for “war dead” at Google Image. Perhaps everyone should do that once, but it’s not what is needed on a daily basis. What is needed is to be reminded not only of the need to honor the dead, but also of how profoundly they and we are being dishonored every day by war’s vulgar contempt for decency.

Photograph by Peter Nicholls/The Times (UK).