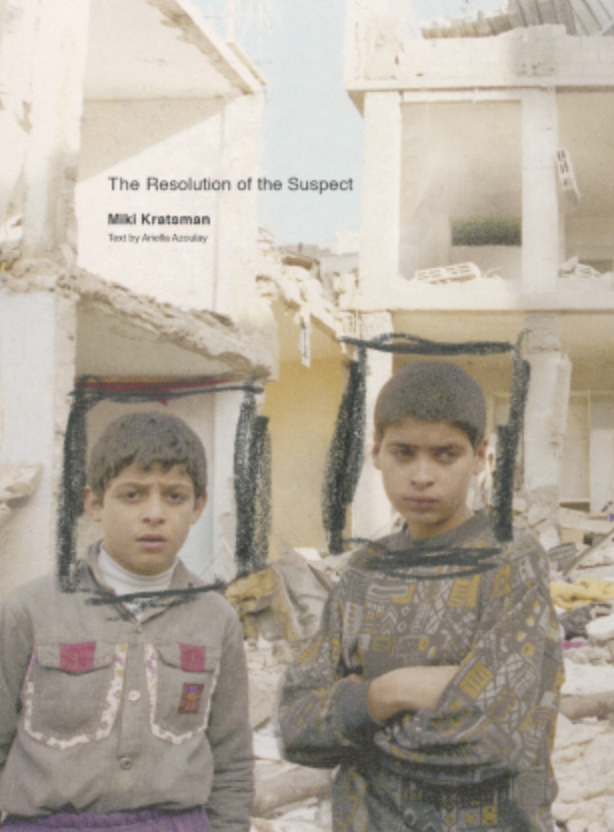

Radius Books, in conjunction with Harvard’s Peabody Museum Press, has released The Resolution of the Suspect, a collection of photographs by Miki Kratsman with accompanying text by Ariella Azoulay. The work draws on decades of documentary engagement in Palestine to expose the operations and effects of the Israeli occupation.

Prepare to be disappointed: if, that is, you want to see searing moments of human drama, striking images evoking strong emotions, and compelling indictments of political leaders. Such photographs have their place, but to show how oppression eats into the bones of all who are involved–victims and perpetrators and spectators–one has to give up drama for banality.

Aware of both the moral capacities and the limitations of texts and images, Kratsman and Azoulay refocus conventional documentary practices to explore how power shapes the act of seeing. They expose the dominant gaze of military occupation, but more as well. Across the terrain of power, they trace the countless gestures, silences, concessions, commitments, and sheer persistence that make up a politics of presence for those who are denied the status of citizens. The result is a slow, disruptive look into a place where everyday life is lived–and degraded–under the twined optics of nonrecognition and surveillance.

What is most distinctive, and perhaps astonishing, is how Kratsman and Azoulay call for the active participation of the spectator. “Active participation here means to resist the assumption that the insecurity of the lives of those photographed is unrelated to your own status and mode of being as a citizen of a given political regime”; it is to understand instead how “the constitution of your own citizenship is what keeps them vulnerable and exposed to disaster” (28). Nor is this a simple scolding; instead, “We are encouraged to harness our imagination” in order to recognize how we already are being harmed by the illusions of non-participation, and how we have forgotten our right not to be complicit with the perpetrators, and how we, too, can become subject to forces of degradation and destruction.

In place of drama and strong emotional identification with the victims, we are offered a long view and photography’s “civil contract” whereby all who are governed can experience an egalitarian solidarity across the arbitrary restrictions of sovereignty. That contract is available every time you look at a photograph. It becomes a political resource as you allow the photo to prompt and guide your civil imagination. Only then can you enter into what really is happening on the ground while considering what could and should be otherwise.

What you can’t do is see it all. That incapacity is fundamental to Resolution, which offers a collection of fragments that suggest instead how low-level violence can tear, gouge, and distort reality; how it breaks continuities of trust and vision; how sharper resolution is but the ironic echo of an inchoate abyss.

That said, the book is strangely hopeful. I’m not sure why, but perhaps the authors know that cynicism only perpetuates the status quo. I also suspect that they believe in the spectator. However hard it may be to believe, they believe in you.

Discussion