The 8th William A. Kern Conference on Visual Communication

Rochester Institute of Technology

April 26-28, 2018

Design, Sound and Vision in Midcentury Media

Call for Papers

The 2018 Kern conference will be focused on the topic of “midcentury media.” The traditional focus of the Kern conference is visual communication, and this year’s aims to reveal how the visual intersects with broader dimensions of media, such as design, literature, and music. Further, we want to do some ‘looking backward’ to historicize visual culture by focusing on the midcentury period, roughly between the 1940s and the 1960s. We are looking for papers on topics of how media technologies were introduced, visualized and promoted; how design, photography, print, and other visual technologies created glamourous imagery, often of midcentury media objects themselves; how the midcentury literary and popular imagination elicited and relied upon visual displays and representations; and how Cold War anxieties, ideal lifestyles, and optimism for the future impacted midcentury media. We aspire to promote efforts to think about design and modernism within a larger frame of visual culture. We are particularly interested in under researched areas, case studies, and figures.

We encourage submissions that:

• Re-imagine and reassess midcentury media

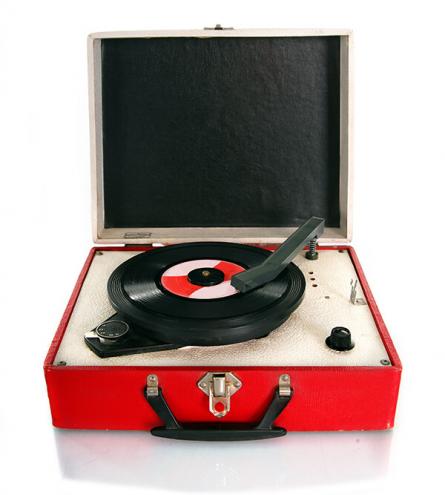

• Explore the continuing significance of midcentury aesthetic production and material culture, including graphic design, vinyl records, radio, television, film, popular media, and ephemera

• Interrogate identity – race, class, gender – and ideology

• Integrate approaches to communication, design, history, media studies, and visual culture

Preliminary list of invited speakers:

Greg Barnhisel, Department of English, Duquesne University

Michael Brown, Department of History, Rochester Institute of Technology

John Covach, Institute for Popular Music, University of Rochester

Keir Keightley, Faculty of Media & Information Studies, Western University, Canada

Kristin L. Matthews, Department of English, Brigham Young University

Monica Penick, School of Architecture, University of Texas at Austin

Tom Perchard, Department of Music, Goldsmiths, University of London

R. Roger Remington, College of Imaging Arts and Sciences, Rochester Institute of Technology

Penny M. Von Eschen, Department of History, Cornell University

Following in the tradition of Kern conferences, we plan a rich program of interdisciplinary scholarship and conversation.

Conference Chairs: Jonathan E. Schroeder, William A. Kern Professor of Communications, Rochester Institute of Technology and Janet Borgerson, City, University of London

Submission deadline: January 15, 2018. Additional information is here.

Send extended abstracts (500 – 2500 words) via email to Jonathan Schroeder: jesgla@rit.edu