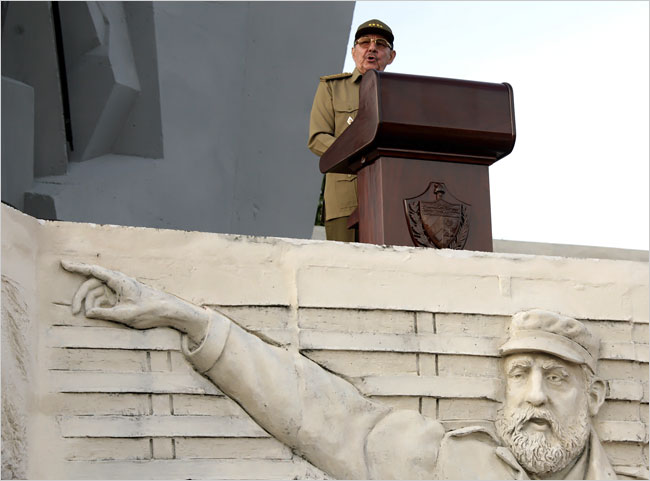

Recently I suggested that photojournalism includes an iconography of body parts that are used to communicate emotions, attitudes, relationships, and the other elements of political experience. Coverage of the celebration of the 54th anniversary of the Cuban revolution is a case in point, and also a brief lesson in the politics of photo selection. Let’s start with this photograph of Raul Castro speaking at the ceremony:

Raul is not exactly shown to advantage here. By contrast with the concrete bas relief of Fidel in front of the podium, he is a diminutive figure set into the background of the scene. Fidel is cut to heroic dimension, bold, direct, and resolute. Raul is like a Lil’ Bush, outmatched even by the lecturn blocking him off from Fidel, the audience in Camaguey, and the viewer. Most important, Fidel is pointing in a classic elocutionary pose as the leader pointing the way into the future. Although looking along the same line of sight, Raul’s arm is stuck next to his side as if he were a stiff, bureaucratic functionary. The implication is clear: Raoul is not the bold, active leader of a revolution. And since that leader is already set in stone while no longer on the political stage, he’s no longer a factor either. Whatever the past glories of the Cuban revolution, it seems apparent that the future will be dull, inert, doomed to decline.

But that’s not the only photo available. Some papers showed this one:

Here Raul still has to follow behind Fidel, but now the comparison is altered on both sides. Fidel now is not just pointing but doing so to give elocutionary inflection to his speech before a bank of microphones. Raul also is speaking before a row of mikes and he is pointing; instead of a lifeless speech shown up by an image of bold action, we have two speakers making an emphatic point in much the same way. Perhaps its much the same point; in any case, the photo becomes a story of continuity. Raul may be no Fidel, but he obviously knows the role and is playing it with gusto while leading the state in the same direction.

And, fittingly for Cuba, between decline and progress there also is a third alternative.

Now we have a more complicated scenario. Both Castros are set back while Che enters the tableau. This ghost of the revolution is set at an oblique angle to both Fidel and Raul. He also is set in a shadow that neatly follows the line of Fidel’s arm. That arm is no longer the dominant signal but rather the transition between past and present. This image has more ambivalent implications. The left-right-up succession goes from dead to nearly dead to living but perhaps geriatric leader. That would suggest decline. But there also is a deeper continuity from martyred idealist to bold founder to ordinary official. Raul may be less than his older brother, but he is grounded in their achievements and remains heir to the spirit of the revolution.

Three photographs, three stories. Regardless of what the photographer is thinking when the picture is taken, by the time the photo is published, photojournalism is an art not only of description but also of prediction and political judgment.

Photographs by Associated Press.

The classic phrase “standing on the shoulders of giants” also comes to mind.

Fidel Castro would always be an icon of history evethough he is against the U.S.,*~

Fidel Castro still have some good legacies despite his not so good repuation.`;,