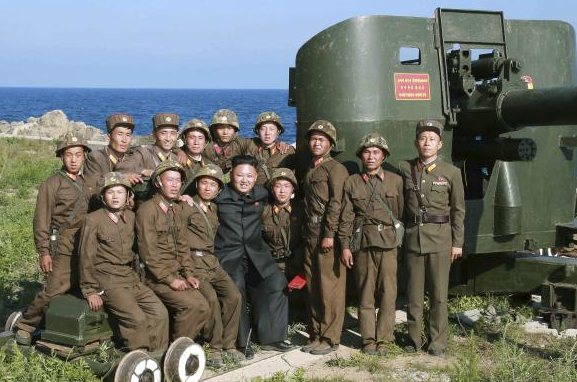

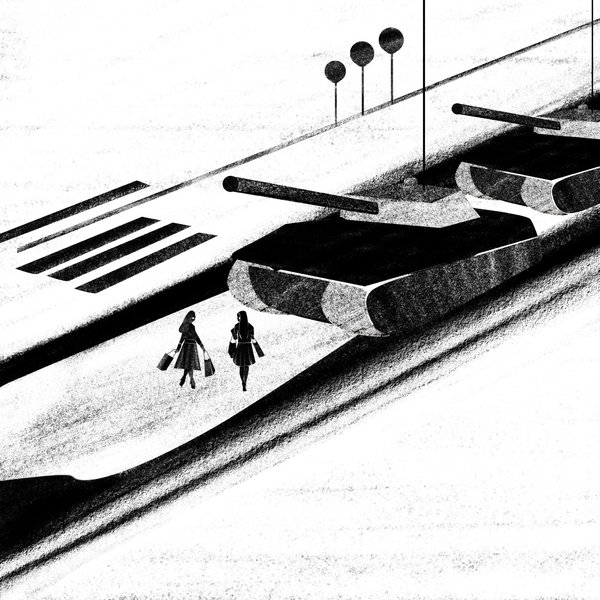

July 17, 2014. The day started with this photograph front page above the fold at the national print edition of the New York Times.

The Times published a report on the image by the photographer, so they must have known that, amidst the hundreds of photographs of the Israeli assault on Gaza, this one touched something deeper that the rest. It had moved a friend to send it to me after it appeared the night before in the digital edition, and I was torn about whether to write about it. On the one hand, it is a work of art that confronts the viewer with more than the public wants to know, it exposes the moral obscenity on both sides of the tragedy in Gaza, it highlights the incongruity between the suffering there and the desire everywhere to live with some semblance of prosperity and hope, and it does so by using photographic conventions that have long been ridiculed for their superficiality, sentimentality, and manipulative bad faith. On the other hand, I didn’t want to say anything because I’m just sick with the madness of it all.

And that was before the news that came in during the afternoon.

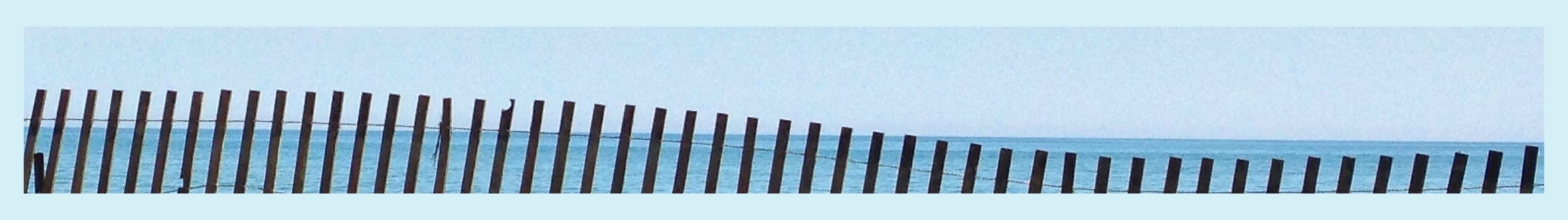

This is what is left of the Malaysia Airlines flight 17 after it was destroyed over the eastern Ukraine. It looks like a garbage dump in hell, complete with minor functionaries overseeing the wreckage. When coupled with the graphic tracking how all commercial flights subsequently are detouring around Ukrainian airspace, it also doubles as an image of what war does for economic development. You can bet that the one pattern will become a model for many others. But that is the least of it. Look at the photograph again. There used to be 298 people sitting in rows, minding their own business, and now they have been obliterated.

That may be why the few people wandering through the wreckage are an important part of the photograph. They are looking, because that is all they can do. That is all the viewers of the photo can do. There is no possibility that the photo might impel some action that would make a difference to those now destroyed. No one is able to reverse the flow of time, pull the incinerated flesh and shattered materials back together, bring everything back to life as it was being lived, as it should be lived. We have arrived at a crime scene, and too late to do anything but ask why.

And not the only crime scene. Girls are still enslaved by militias, villages terrorized by gangs, populations herded into camps. . . . Despite vast numbers of people living in relative prosperity and safety, that same world seems to be coming apart at the seams. As I’ve argued elsewhere, if the 21st century is experimenting with forms of violence, they would be visible at the margins: in failed states and quasi-states, occupied territories and zones of anarchy. Photography is already there, documenting the texture of destruction that is unfurling around the globe. Perhaps some day we will look back and say, “Oh, there clearly was a logic to it.” But that will be more than hindsight, for it also will be a mistake.

Whatever is happening, it is madness.

Photographs by Tyler Hicks/New York Times and Dmitry Lovetsky/Associated Press.