In her widely influential book On Photography, Susan Sontag famously argued that photographs of atrocities dull moral response. Twenty-seven years later in Regarding the Pain of Others she issued a partial retraction: People can become habituated to images of violence, but some photographs for some people can continue to shock and thereby prompt moral reflection. The images cannot provide anything more for critical self-assessment, however: that was “a task for which the painful, stirring images supply only an initial spark.”

Surprisingly, this often is taken as a sufficient recalibration of the role photography can play in the public sphere. By contrast, John and I believe that Sontag continues to stand in the way of understanding how photography is an important public art. We also believe that a paradigm shift is already underway, albeit fitfully, in the discourse of photography as it is used in public, professional, and scholarly forums. (We are developing a book to set out this argument in more detail, and a few readers of this might have noticed that we’re running out parts of it in some of our posts.) The dominant but ailing paradigm was authored by Sontag and other writers a generation ago, and she remains its boldest, clearest, and most widely imitated exemplar. The fact that Sontag came to challenge a central idea in the conventional wisdom that she helped propagate is reason enough to assume that a paradigm shift is needed and well underway. Unfortunately, Regarding the Pain of Others also reaffirms too many of the conventional assumptions about photography that were set out in On Photography. To summarize very briefly:

1. Photographs continue to be ”a species of rhetoric” that “simplify,” “agitate,” and create the “illusion of consensus”; they are ”totems” and “tokens” rather than adequate representations, and also “like sound bites” and “postage stamps”; they “objectify” and yet also are a form of “alchemy” that either beautifies and thereby can “bleach out a moral response,” or uglifies and thereby can at least evoke an active response; they require no artistic training and so have led to “permissive” standards for visual eloquence; they depend on a “slight of hand” and a “surrealist” aesthetic that with the ascendency of capitalist values is thought to be realism; they compare unfavorably with or have an unfair advantage over other arts, especially writing; they depend absolutely on written captions for their meaning, and while they can shock, “they are not much help if the task is to understand,” something that can only come from narrative exposition.

2. The Public that consumes these images has matching characteristics. They take for granted their privilege, safety, and distance from the events being reported, they are alternately “voyeurs” or “literalists”, and “spectators or cowards,’ while the “indecency” of spectatorship is of a piece with those who enjoyed viewing photographs of lynching or “colonized human beings” from Africa and Asia; they are being corrupted by television and are prone to remember only images, not the stories that could provide complexity and understanding. These public images are supplied by photojournalists, who are “professional, specialized tourists,” some of whom become celebrities whose pronouncements can be so much “humbug.”

3. Moral response to a photograph is acknowledged to be possible, even after repeated exposure to images of violence, but also severely limited. Photographs serve the public by shocking the viewer, but they leave “opinions, prejudices, fantasies, misinformation untouched”; and they also can go too far, making suffering “abstract” and thus fostering cynicism and fatalism; and the emotions of compassion or sympathy that are elicited are “unstable,” tend toward “mystification of our real relations of power” and so are “impertinent”; in any case, they “cannot indicate a course of action.”

In short, moral response to a photograph can at best be only a surge of raw emotional energy that is devoid of the rational capabilities necessary for ethical relationships. The public is locked into spectatorship rather than authentic participation and thereby given only poor or worse options for ethical living. Photography may be put to better or worse uses but remains a profoundly suspect medium of representation, indeed one that is inherently fraudulent because the image can never provide the adequate knowledge of reality that is promised. Thus, Sontag’s reconsideration of photography remains locked into the same modernist binaries that it needs to challenge.

This summary does not pretend to do justice to the nuance and depth of Sontag’s thinking, but we do want to suggest that her second thoughts remain all too consistent with her early and still highly influential discourse. While Sontag’s contribution has been enormous, it is not without hidden costs—costs that even she continued to pay. So it is that Regarding the Pain of Others provides one example of what it means to work within and against a paradigm that is becoming increasingly out of synch with its subject. Sontag sensed that her original discourse lead to some seriously mistaken conclusions, yet she could not scrap it entirely (who could, in her position, or in ours, for that matter?). Thus, the book has a high degree of internal inconsistency—like the habitus of photography itself today. Both text and context are still beholden to a vocabulary and set of assumptions that need to be re-examined. They never were entirely accurate, but at one time they were sharp enough to mount a progressive critique of an important public art. They are not now wholly inaccurate—far from it, as they identify deep risks of media dependency—but they do not provide the conceptual resources that are needed to understand the many roles that photography can play as it is a public art and mirror of modern life.

One of the ironies of Sontag’s critique is that she consistently compares photography unfavorably to writing while also citing Plato as one of her authorities on the dangers of mediation. Most notably, Sontag faults photography for how it makes humans insensitive to their distance from others while corrupting collective memory. In each case, she turns to narrative exposition for the necessary corrective. The problem is that when Plato identified those dangers (see his dialogue Phaedrus), he was referring to writing. And he was right–not only about writing but also about communication media in general. One theoretical task, then, is to find the right way to think about photography as a specific medium that is neither immune from, nor unduly responsible for, widely distributed problems of human communication and political community.

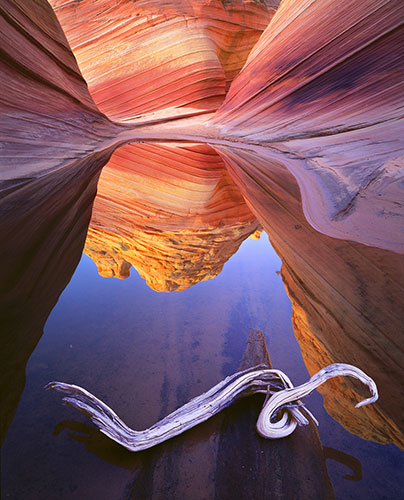

And so we finally can turn to the photograph above, which admittedly I am using as a token. Sontag would be correct on other points as well: for example, you don’t know much about the event until the caption informs you that the man’s throat had been slashed during the religious war in the Central African Republic, and that he was being rescued by French soldiers. Look closely, and you very likely will be shocked as well; and that alone is very likely not to lead to much in the way of action.

But is that it? And are you really looking at only that photograph, rather than seeing it as one part of a much larger archive of images, along with an extensive history of immersion in print journalism, history, literature, and other arts? (In W.J.T. Mitchell’s important declaration: All media are mixed media.) If neither “voyeurism” nor “sympathy” is the right term to describe your response, what is in the middle ground of more ambiguous reactions? If moral knowledge has to be both abstract and concrete, might this image or one like it provide a partial outline of what one needs to know? And of how the public spectator might be implicated in the violence?

The image isn’t merely a token, and it is not a philosopher’s stone either, but that leaves a lot in between. If photography is capable of imparting, modeling, or constituting moral knowledge, we have a lot to learn.

Photograph by Michaël Zumstein/Agence Vu. For examples of the argument that photography can do more than shock, see, e.g., Susie Linfield, The Cruel Radiance: Photography and Political Violence, Sharon Sliwinski, Human Rights in Camera, and our own No Caption Needed: Iconic Photographs, Public Culture, and Liberal Democracy.

2 Comments