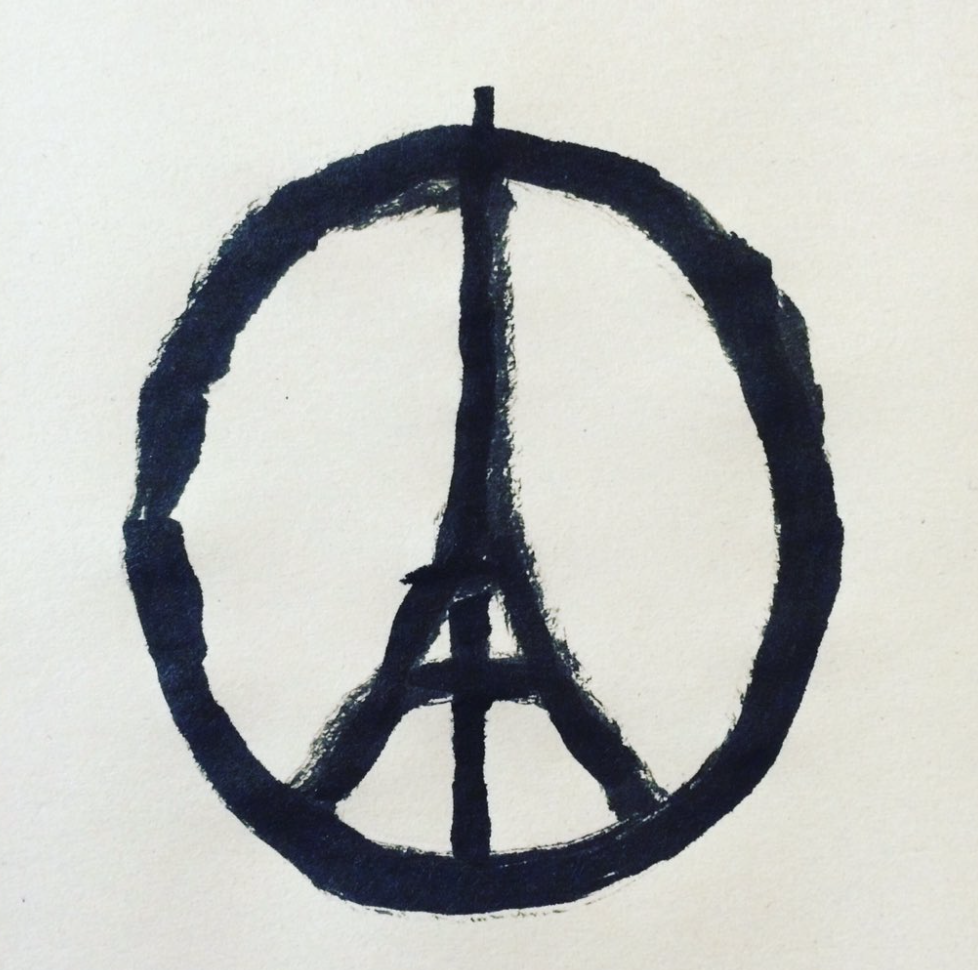

The drawing by by French graphic designer Jean Jullien has become one of the more widely shared artworks about the carnage in Paris. Like many of them, and like some of the photographs being shared, it includes the Eiffel Tower. Which is why the cynic might want to say that for all of the emergency claims being made, it’s still business as usual in the West.

To push the point, one might ask whether public opinion can ever get beyond tourism. (Susan Sontag argued that photography turned everyone into tourists, who were content to have only minimal knowledge and inauthentic relationships.) The outpouring of emotion far exceeded that spent on the ISIS bombing in Lebanon a day earlier or the ISIS destruction of a Russian airliner before that. I guess Beirut needs a tower, and the Russians need to paint Red Square on the side of their planes. The differences in coverage and response will depend primarily on powerful ethnocentric biases in the political and media systems, as well as the differences in the scale of the attacks, but one can’t help but think that the a lot still depends on the available symbolism.

That said, I think the critique is another example of how the cynic knows the price but not the value of things. The attacks were an assault on the city itself–and on its image as a beacon for living well in a modern civil society. Whatever the analysts might say about the political maneuvering of France in the Middle East, it was not the government buildings that were targeted. The city of light and love was attacked for what it was. What better way than the Eiffel Tower to communicate globally and instantaneously that we know and value what is at stake.

I think Jullien’s design is superb for other reasons as well. The Vietnam War era peace symbol has deep resonance for many of us, and it evokes two very important ideas: That once again a truly vile war is being waged, and that international solidarity is required to stop it.

Times have changed, of course: unlike North Vietnam, ISIS hasn’t a shred of legitimacy. But some things also stay the same: a string of unintended consequences has lead to disaster, and before this war is over many lives will be ruined for many years to come. More tellingly, the movement to stop ISIS can’t be only a peace movement, and those defending the West will have to also beware how war will transform their own societies. The effort to stop a ruthless tyranny also can lead to a national security state where the Paris of today is only a memory. The brand would continue, of course, but that really would be mere tokenism, like one of those miniature Towers that you can buy on the street.

And so the cynic might have a point after all, although not about branding. To defend Paris is to defend civil society as it is, with all its mashups of art, technology, commerce, politics, and everything else (including religion) that crazed ascetics would ban or segregate. But what about mashing up war and peace? The beauty of Jullian’s simple illustration is that it is a call for peace, and perhaps a claim that peace will triumph. It has arrived, however, just as France and other nations (including You Know Who across the pond) are gearing up for war.

Cross-posted at Reading the Pictures.