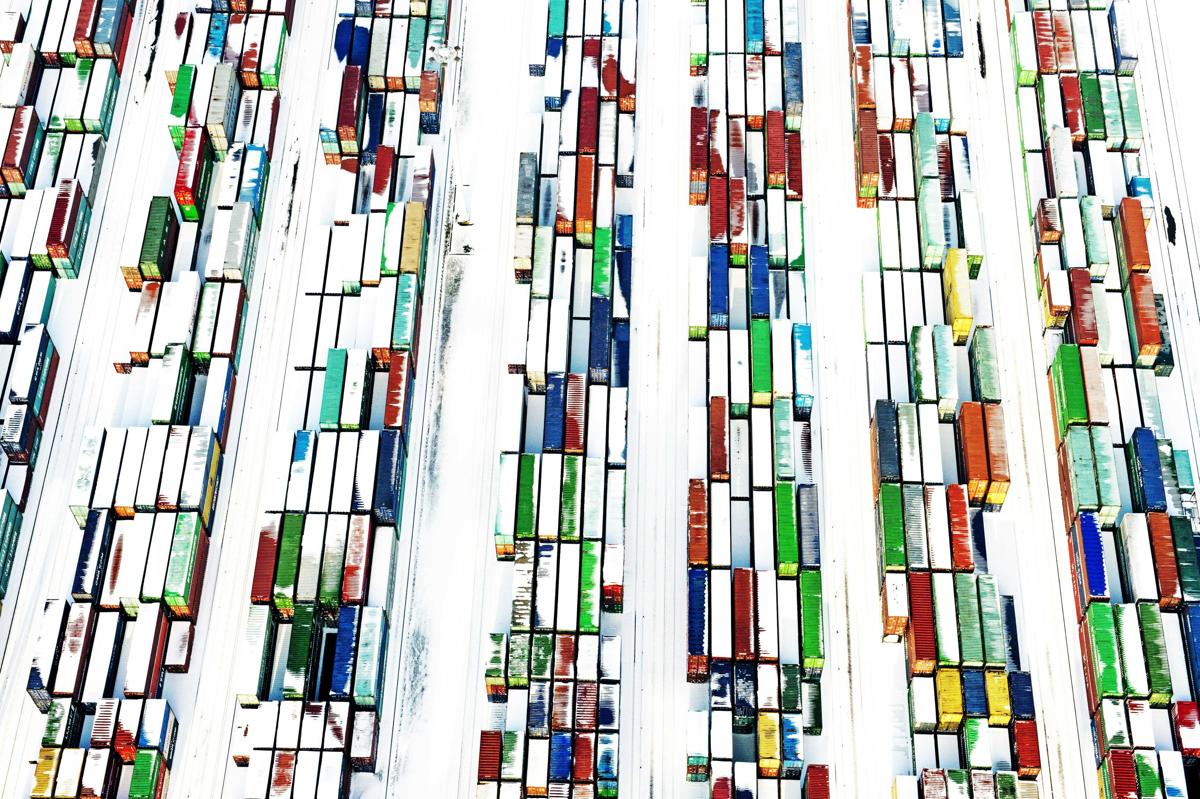

It could be a circuit board, or a strip of DNA, or a bit of jewelry, or a painting. Whatever it is, it is orderly, yet not too severe; colorful, but no riot of brash hues; uniform, yet also pleasantly varied; textured, but simply so; a collection of many things, but still a study in form; abstract, yet somehow familiar–almost like crayons in a box, although it may be much bigger than that. Small/large, micro/macro, ordered/varied, colored/white, delighting the eye yet immobile, still, serene.

The caption said, “Snow covered containers decorate the port of Rotterdam, The Netherlands on January 15, 2013.” You really don’t see a port, though, or anything quite so institutional. The key is in the verb: “decorate.” Exactly right. And “snow covered” is right, too, even though it’s not literally correct: many of them are not covered with snow, but the phrase captures the feel of the image, the way in which the ordinary sense of things can be covered by a blanket of snow and seemingly transformed, as if by magic, into something quiet and beautiful. Or, you might say, the way snow can damp down the ordinary way of seeing objects–that is, in all their detailed functionality–so that we can experience the quietude that always lies in the small spaces between things.

Let me suggest that there is another sense of serenity that also might be available here. Like the snow, the shipping containers are only in a temporary repose. They have moved and will move again, to flow though circuits of trade that span the globe. The miniaturization achieved by the camera symbolizes the relationship of this one scene to the vast, dense circuitry of the global economy. What it captures, however, is not the dynamic movement of goods, information, and capital, but rather the stability in the system as a whole. That stability is not inert–like the weather, it is one feature of a system that is constantly changing–but there can be something to admire in its impersonal replication, week after week, month after month, like strands of DNA replicating again and again within a global organism.

From the view on the ground, this is nonsense, of course. The shipping industry consists of thousands of variable decisions being made at every level, all while being buffeting by winds of change over which they have no control: government policies, market conditions, technological developments, even the weather. But that’s why the view from above can be valuable. Instead of seeing only competition, friction, and another day’s work, we can see the deep sense of decoration: how the small ornament can mirror a cosmos.

“The serenity of networks” alludes to one of the classic works on the Internet: The Wealth of Networks, by Yochai Benkler. His title in turn alludes to The Wealth of Nations, by Adam Smith. The relationship between digital networks and market economies is still being explored, but each has prompted the dream that we can find in the impersonal processes of large-scale exchange something more reliable than the political behavior that so often disrupts, destabilizes, and leads to want, anxiety, and anger. The dream is not impossible, but it will not be realized without political organization.

If only that politics could start with an image such as the one above. An image that is surely decorative, but not merely so, as it also suggests how abundance can be a stable resource, orderly yet varied, complex yet reliable, grounded in what we do well and not in ignorance, fear, and anger, waiting only to be distributed where it is needed. Something that could be done, you know. . . .

Photograph by Robin Utrecht/EPA.

Cross-posted at BagNewsNotes.