Keeping the Faith on Election Day

The caption reads, “Head precinct judge Deloris Reid-Smith reads the voter’s oath to poll workers before opening the polls at the Grove Presbyterian Church in Charlotte, North Carolina November 4, 2014.”

A few people complain occasionally about the fact that voting is conducted in churches. Separation of church and state is more virtual than material some of the time, and so custom rules on this one. Besides, churches often look more like schools, right down to the basketball backboard above the multipurpose flooring. But I digress.

What really counts is how the election is conducted. If done right, the voting procedures will be impartial, without any hint of coercion or corruption, and accessible to all without great inconvenience or other disruptions. It should be so routine that it appears completely ordinary and even banal. At the same time, however, voting must have the safeguards that are applied to any activity that is essential for the survival of the community. Voting is crucial for many questions of collective material and ethical well-being, and it is an absolute necessity for democracy itself. You might even say that maintaining the integrity of the election a sacred obligation.

Which is why this photograph gets it exactly right. We see both the incredibly ordinary, routine, banal decor of everyday life, and the taking of an oath. A place that can be filled with a dozen different activities in the course of a week, now is being dedicated to a single civic duty. Ordinary people who will go their separate ways at the end of the day, are placing their hands together on a Bible in a common testament of their commitment to a fair election. They pledge only that, but it is enough.

Elections today–especially today–are fodder for cynics, and some may see the photograph as an other example of how voting in the US has become an empty ritual. To go further down that path, one might ask where the Koch brothers served as poll workers. The billions spent in the last year did nothing to enhance the integrity of election day, and it would be easy to conclude that the poll workers’ oath is the last, pathetic example of idealism, or niaveté, in the entire system.

That may be true, but at least they, and the photographer, have shown us what election day is supposed to mean.

Photograph by Chris Keane/Reuters.

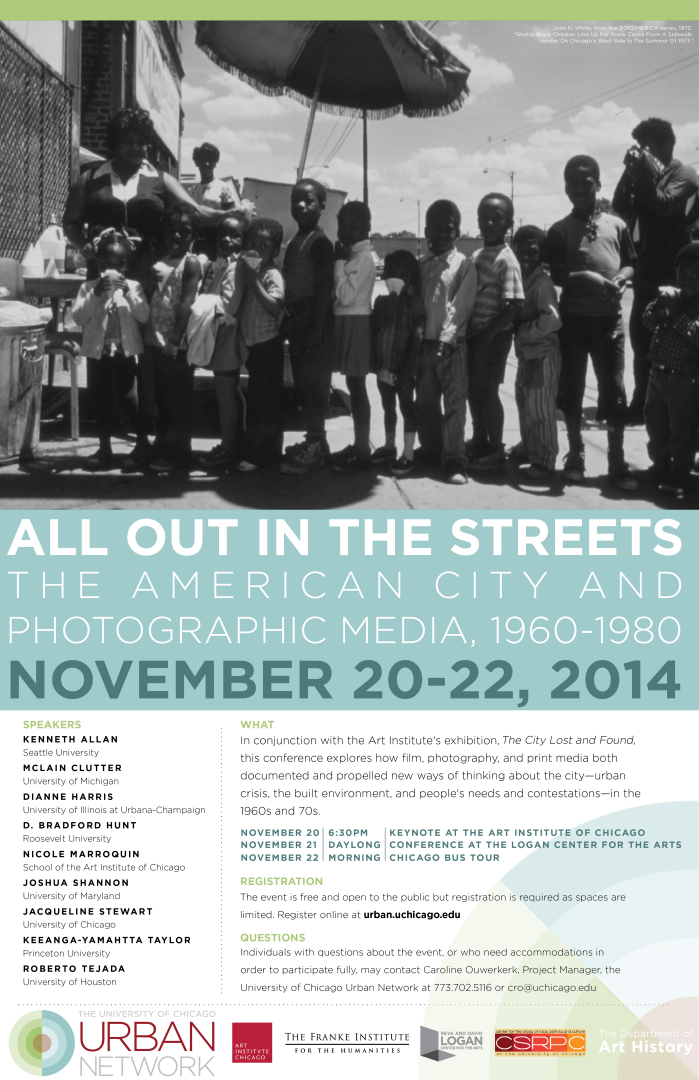

Symposium on Securing the Image

Symposium on Visual Rhetoric

Securing the Image: Surveillance, Verification, and Global Violence

Northwestern University

Annie May Swift Hall

November 1, 2014

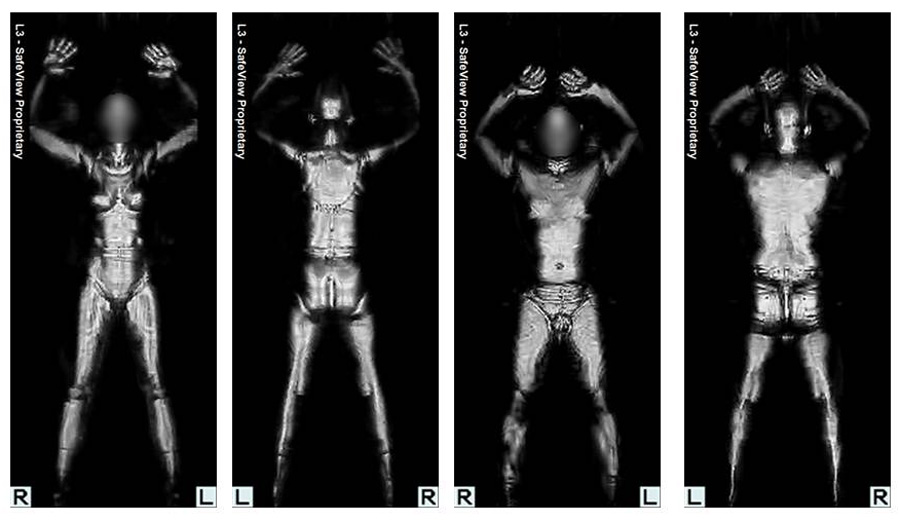

Somewhere between the worldwide adoption of digital imaging technologies and the Global War on Terror, photographic documentation became both highly suspect and increasingly important. Questions regarding surveillance, manipulation, and other factors in image production have become occasions for inquiry into some of the most basic assumptions about visual media and public culture. These questions acquire additional significance when visual practices are intertwined with violence done in the name of national security. At the same time, they offer new vantages for rethinking the nature of the image and its aesthetic and political possibilities. The symposium on Securing the Image includes two public lectures devoted to reconsidering key issues in visual surveillance and verification:

9:00 a.m. David Campbell, “Manipulation, Scraping, and Verification: Securing the Integrity of Visual Representations of Political Violence”

10:30 a.m. Rachel Hall, “Asymmetrical Transparency: The Global Politics of Risk Management”

David Campbell is the A. Lindsay O’Connor Professor in the Peace and Conflict Studies Program at Colgate University. He is the author of six books and more than 60 articles, and has produced visual projects on the Bosnian War, imaging famine, and the visual economy of HIV-AIDS. As a research consultant to World Press Photo he directed their 2012-13 Multimedia Research Project and a 2014 project on “The Integrity of the Image.” He is also Secretary to the World Press Photo Contest. David produces multimedia and video projects, and all his work can be seen at www.david-campbell.org.

Rachel Hall is Associate Professor of Communication Studies at Louisiana State University. Her publications included Wanted: The Outlaw in American Visual Culture (University of Virginia Press, 2009), The Transparent Traveler: The Performance and Culture of Airport Security (Duke University Press, 2015), and articles in Performance Research, Women’s Studies Quarterly, The Communication Review, Camera Obscura: Feminism, Culture and Media Studies, and Hypatia: Journal of Feminist Philosophy.

Sponsored by the Center for Global Culture and Communication and the Department of Communication Studies/Program in Rhetoric and Public Culture. For additional information contact symposium organizer Robert Hariman (r-hariman2@northwestern.edu) or administrative assistant Dakota Brown (jdakotabrown@u.northwestern.edu).

What Is Near and Far in the Geography of an Image?

It’s not quite a Monet, but I think it deserves to framed. Cezanne might be the better comparison, but this photo is more about distance than mass and volume. And curiously, just where it gets close to abstraction, it also gets closest to the stiff demarcations and solid identities of American folk art, which may seem stranger still for an image from Siberia.

The photograph was one of many in a slide show at In Focus on autumnal beauty. Fall is my favorite season, and In Focus one of the best photography sites on the Web, but even so I was prepared to be underwhelmed. I expected to see the same images we always see at this time of year, the same colors, the same sameness. Perhaps this photo seems no different to you; harvest scenes are part of the repertoire and the transition into dormancy and quietude is part of the seasonal mood, so the conventions still are in place.

Consider, however, how the image sits a bit off center, like the hay bales in the photo. The mood is not so much autumnal as more profoundly liminal. Not so much fall in all its glory, but as if we are on the edge of winter, just as the field is on the edge of the lake. And is that deep, solid blue a fall color? It seems to be something out of time, almost as that lake seems out of place in the midst of a harvest scene. For these reasons and more, the photograph strikes me as more distinctive than many of the stock images of the season. And both more beautiful and somewhat unsettling for that.

So what is unsettling, beyond simply deviating a bit from convention? Let me suggest that this image is a masterful study of photography’s subtle deconstruction of spatial perception. Notice how the composition is a series of borders: the strip of snow in the foreground, the strip of field immediately beyond that, the rest of the field, the beach, the lake, the far beach, the strip of trees, the sweeping uplands, the mountains (or are they clouds?), the sky. . . . The visual expanse is a continuous succession of separate, parallel spaces, each of which becomes a border between two others. As they eye transverses from front to back along the empty center axis to the vanishing point, one might conclude that there is no there there. More to the point, the swaths of color and dabs of light seem to have been laid down on the flat surface of a canvas: the distance is but an illusion, a trick of the eye.

And yet we also see the sheer particularity of the pieces of hay sticking out of the two bales in the foreground. They are unquestionably near, while the other bales are far away. So it is that reality and illusion continue to interrupt one another. The same holds across the visual field of the photograph. Every place within the scene has a sense of extension yet also is interrupted by another; each one is unique and yet unable to either connect with or subordinate the others to create a sense of unity. Hence the comparison with Cezanne, as the material autonomy of each part of the work reveals an underlying sense of form, but one that refuses to channel a transcendental unity, leaving instead the specific weight of each part of the painting itself and with that its autonomy, a substitute for transcendence, as a work of art.

But it’s not a painting. And those bales and Lake Belyo are actually in Siberia, which is a very long way from where I am writing this post. Photographs are valued because of how they can bring distant views close at hand, and they are faulted for introducing unnecessary distance between the viewer and reality itself. Both reactions capture important elements of photography’s geographic capacity. This photograph fits either one perfectly: it has brought a distant scene into view, and it encourages aesthetic habits that could buffer my experience of the seasonal changes happening right outside my door. I may become accustomed to scenes that are empty in more ways than one, and yet I have been given a view of a beautiful world that extends far beyond the borders of my daily life.

Let me suggest that the photo takes us beyond this standoff. It suggest not only that any photograph is both far and near (and we knew that), but also that what matters are not the distances but the relationships. The image reflects the compositional processes that create photography’s internal space, with each photograph a virtual world in which space–and time–can expand and contract almost at will, but not to obliterate the distinctions that had been laid down in reality. Likewise, each photograph can be thought of as a liminal space: a threshold between two worlds, each of which in turn can lie between two others in a continuous succession of experiences, none dominating the other. Some appear to be near, others far away, but that may be the most complete illusion.

Photograph by Ilya Naymushin/Reuters.

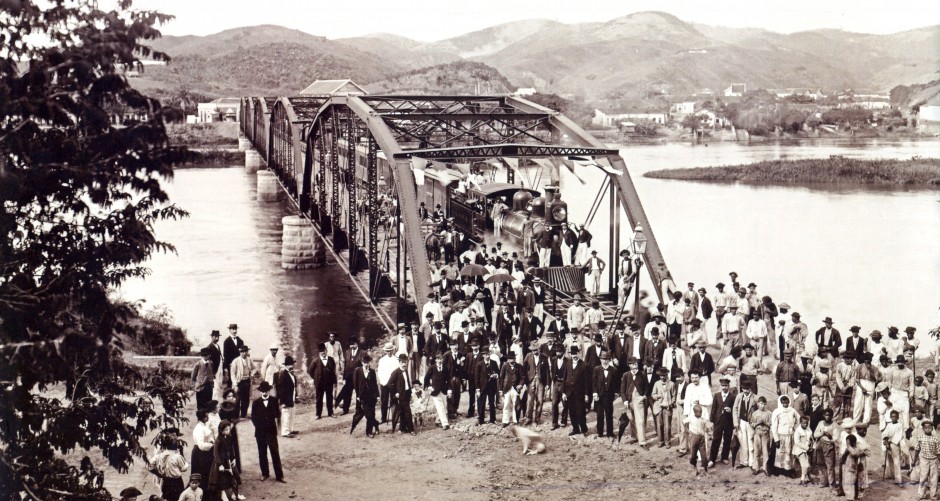

Paper Call: Photography and Migration

Photography and Migration

Colby College, Waterville, ME

April 24-25, 2015

On April 24-25, 2015, scholars, artists, students, and members of the Waterville community will come together at Colby College to interrogate the relationship between photography and migration. This conference is one of many events taking place at Colby that address the college-wide humanities theme in 2014-2015, “Migrations,” hosted by the Center for the Arts and Humanities. It will include formal presentations and roundtable discussions, film screenings, as well as displays of historical photographs and artworks.

Throughout its history, the photographic medium has played an important role in the movement of people, objects, identities, and ideas across time and space, especially in the human crossing of geographical and cultural borders. Scholars have shown how cameras documented, enabled, or controlled such forced and voluntary movement, while photographers attempted to put a face on immigration around the world, making visible its associations with transition, displacement, hardship, and opportunity. The goal of the conference is to consolidate and expand upon the critical questions asked about photography and migration. What does it mean, for instance, to represent photographically the experiences of immigration, exile, diaspora, and passing? How might we reimagine concepts essential to migration, such as (im)mobility and dissemination, in specifically photographic terms? How do photographs themselves, moreover, migrate across local, regional, national, and global contexts?

To stimulate lively and productive exchanges during the conference, we are soliciting proposals for 10-minute presentations from scholars, curators, image-makers, and others that highlight major questions about photography and migration. Following each presentation will be a short response by a discussant from Colby College and 20 minutes of conversation with the audience. We are looking for proposals that address directly the theme of the conference; foreground their own critical and creative interventions; and engage deeply with a set of images, or even a single image.Please submit the following materials to Tanya Sheehan, Associate Professor, Department of Art, Colby College, tsheehan@colby.edu by December 15, 2014:

- Cover letter; please include your contact information and explain your interest in the conference theme

- Abstract; no more than 200 words, including a working title for your presentation

- Professional bio; no more than 100 words

- Curriculum vitae

Decisions on proposals will be made by January 15, 2015.

Details about the conference will be made available here.

Mirroring Ebola

The caption said, “Health workers enter the high-risk zone as they make the morning rounds at the Bong County Ebola Treatment Unit in Sgt. Kollie Town near Gbarnga, Liberia, Oct. 6, 2014.” Good to know, but not all that is being shown.

So what is being shown? A mirror image, but what is that? And what’s with the visual tricks: isn’t Ebola a serious threat, and shouldn’t the press be emphasizing transparency, clarity, and accountability rather than playing with artistic techniques? We need to know the truth, not be confused about the distinction between image and reality. Or is this a political ruse, taken to suggest that there are more emergency personnel available than is actually the case? Or a critical comment that the number of health care workers needs to be doubled?

Whatever the answers, it might help to ponder the fact that the photographer risked his life to create this photograph. And once at risk, he certainly could have concentrated only on straight-forward reportage, keeping any obvious distractions out of the picture. Yet here we have a photograph that comes with a built-in distraction: divided between a mirror image and the scene reflected, one’s gaze is pulled back and forth, never able to settle on one focal point without having the other as a peripheral vision that disturbs concentration.

Curiously, the second image is troubling precisely because it is too similar to what is being seen directly. Just about anything else could either be disregarded or given direct attention, but the double image keeps undercutting its own validity even as it demonstrates its representational power. Instead of demarcating reality, the image is too close for comfort, uncanny, and suggestive of a truly profound disorientation. Which side is real? How can we tell? What if the mirror has been mirrored?

This discomfort is part of photography’s DNA. Originally valued for its ability to replicate nature, the technology also has fueled anxieties about reality being displaced by an image world. When photographers feature mirror images, they automatically make viewing reflexive, bent back to include both the subject of the photograph and its techniques of composition. The double image reminds us that we are seeing an image rather than reality, and suggests how we can see more, not less, because of that.

The media panic about Ebola has involved massive injections of fear regarding viral replication, contagion, and the ultimate displacement of death, so perhaps an image of photographic doubling can channel or otherwise contain some of the excess emotion. Instead of panic, the doubled image is reflective, creating a space for a slower, more meditative response. Instead of death by contagion, we see an artificial replication that is benign and yet perhaps suited to representing the social system that develops quickly to contain the disease.

And yet, like the oscillation in the image itself, this reflective moment can’t be entirely comforting. The scene is doubly surreal: as if hazmat suits and goggles, emergency tents and water brigades, and the transformation of extraordinary suffering into routines of risk management weren’t enough to deal with, those many dislocations of ordinary life have been doubled, replicated, cast into a space of reproduction that could extend repeatedly around the globe without ever becoming a place one would want for one’s own.

You can decide how much of that picture is image, and how much is reality.

Photograph by Daniel Berehulak/The New York Times.

Cross-posted at BagNewsNotes.

Paper Call: Conference on Media Materiality

Sixth International Conference on the Image

Media Materiality: Towards Critical Economies of “New” Media

Clark Kerr Conference Center

University of California at Berkeley

Berkeley, California USA

29-30 October 2015

The conference web site is here. The call for papers is here. The submission deadline is November 6, 2014.

White Swans and Photographic Seeing

The caption says, “A white swan (lat. Cygnus olor) flies over the Main-Donau canal in Bamberg, Germany, 06 October 2014.” Not that you can see the canal, or Bamberg, or the sky, or anything except the bird suspended in a black void. Nor are the feathers pure white, which you can see in the stock photos that will pop up on Google Image. The bird seems to have been stained by mists of oblivion, as if it were a message traveling through some fantastic system of communication in Middle Earth. Such fantasies may be invited by the stark contrast of the lighted figure and dark background, which makes the bird seem to be a silhouette despite still being visible as a specific individual. The image is both the literal trace of a single animal in a single moment of time, and an abstraction in some undefined cognitive space. There once was a bird passing over a canal, and there is the Swan, a Bird, token of Nature, passing through Life, again and again and again.

Many people spend their entire lives seeing swans without ever seeing a swan. From the preschoolers’ first picture books to Disney movies to advertising to the arts and back again, swans are not rare birds. They are tokens of culture, not a familiar part of nature. One might hesitate then about focusing on photography alone, but the image above does provide an object lesson in photographic seeing. Joel Synder has pointed out that cameras don’t capture images–they make them. The image doesn’t exist until the camera clicks. The image above is a near-perfect demonstration of that distinction. There never was a swan suspended against a black background; those effects were created by the camera. In fact, a swan was flying through a night sky, but the movement has been stopped and the details of the actual optical field have been abstracted out of the picture. And a similar transformation is true of every swan photograph that you have ever seen. Those swans never existed in the rectangular box of the photograph; they are found there only in the image.

Of course, as we have become habituated to photography, we also become accustomed to projecting images: to imagining how photographs could be taken and how scenes are more or less photogenic. We also become accustomed to collecting images: to filling our phones and tablets and heads with expansive vistas, glorious sunsets, and thousands of small ornaments: raindrops on a leaf, leaves on the surface of a pond, the moon reflected in the dark water.

And that’s the hell of it, according to some critics of the medium. Most notably, Susan Sontag argued that “so successful has been the camera’s role in beautifying the world that photographs, rather than the world, have become the standard of the beautiful. . . . Photographs created the beautiful and–over generations of picture-taking–use it up.” Perhaps that’s why we’re down to one swan. Indeed, this “habit of photographic seeing–of looking at reality as an array of potential photographs–creates estrangement from, rather than union with, nature.”

Now that is a serious charge, and although Sontag offers no proof whatsoever, it would seem to be supported by Synder’s account of the image. That silhouetted swan is pure culture, and although the photograph promises to bring you closer to nature, in fact you only are being brought close to an optical illusion. The photo says, “Look, you can see a bird that you never would have seen otherwise,” but you still haven’t seen that bird as it actually moved through a material environment, much less while you were a part of that same environment.

But you have seen something, and something that was amazing, and what you would not have seen otherwise. In that seeing, you have become part of a larger world, and one in which the most ordinary and distant and ephemeral of events–a bird flying across a canal–has acquired special significance. Not meaning, perhaps, but significance, which may be all that we can hope for some of the time. (Some readers may hear an echo of Walter Benjamin’s remark that Kafka “sacrificed truth for the sake of clinging to its transmissibility.”) Photography does transmute reality into images, but to create a common world, which now is one where a swan flies through complete darkness, like a message from a distant beacon.

Photograph by David Ebener/EPA. Joel Synder’s argument is set out in “Picturing Vision,” Critical Inquiry 6 (1980): 499-526. Sontag’s remarks are from On Photography, pp. 85 and 97. Walter Benjamin’s insight is in Illuminations, p.1 44. For an earlier post on this theme, go here.

NCN on Vacation

It’s time to hit the road again. We’ll be back on August 25 October 6 October 13 (really, we promise this time). Truth be told, the vacation has turned into a last push to get our next book to the Press on time (and we did; this last delay is for other reasons, and we’re running out of excuses). We’ll hope that you are busy, too, but not so busy that you’ll forget to check back later in the fall.

Movie still from On the Road (2012).

Artificial Light in Philly

How much can you catch in a flash of light?

A lot.

Artificial Light: Flash Photography in the Twentieth Century is an exhibition at the Philadelphia Museum of Art through August 3. The exhibition web page includes a slide show, along with a video interview with photographer Sara Stolfa, who took the photograph above. You also can see a brief discussion of the show at Time Lightbox. An intriguing review, one that connects flash artistry with the value of compassion, is provided by Ed Voves at Art Eyewitness.