We have written at NCN on more than occasion about the problem of immigration in the U.S., or perhaps more accurately, on the problem of US public policy regarding immigration and the need for reform. Perhaps the dominant visual trope that is affiliated with U.S. immigration policies is the “wall,” a manufactured border that purports to function as a container that separates there from here and them from us. Of course, the problem is that however sophisticated the technology and however large an army of Border Patrols agents we employ, such walls are never impermeable. And so the policy is already and always fated to be a failure.

The real difficulty, however, may not be that we have the wrong solution to the problem so much as we refuse to come to terms with reality of the situation that we are facing. The photograph above is telling in this regard. The caption reads, “Dessert for an immigrant detainee in his segregation cell during lunchtime at the Adelanto center [in San Bernadino, California].” The institutionally grey, steel cell door is something of a wall and it dominates the photograph, cutting across the diagonal, separating inside from outside and the representative of the U.S. from the detained immigrant. The bolt lock on the top creates the impression of security, but the opening in the door makes it clear that total separation is impossible—if even desirable given that apparently some communication and interaction seems at least useful. It is thus, at least in some senses, a visual metaphor for the (as yet incomplete) wall that has been proposed to traverse much of the 2,000 miles of U.S. borderland between California and Texas.

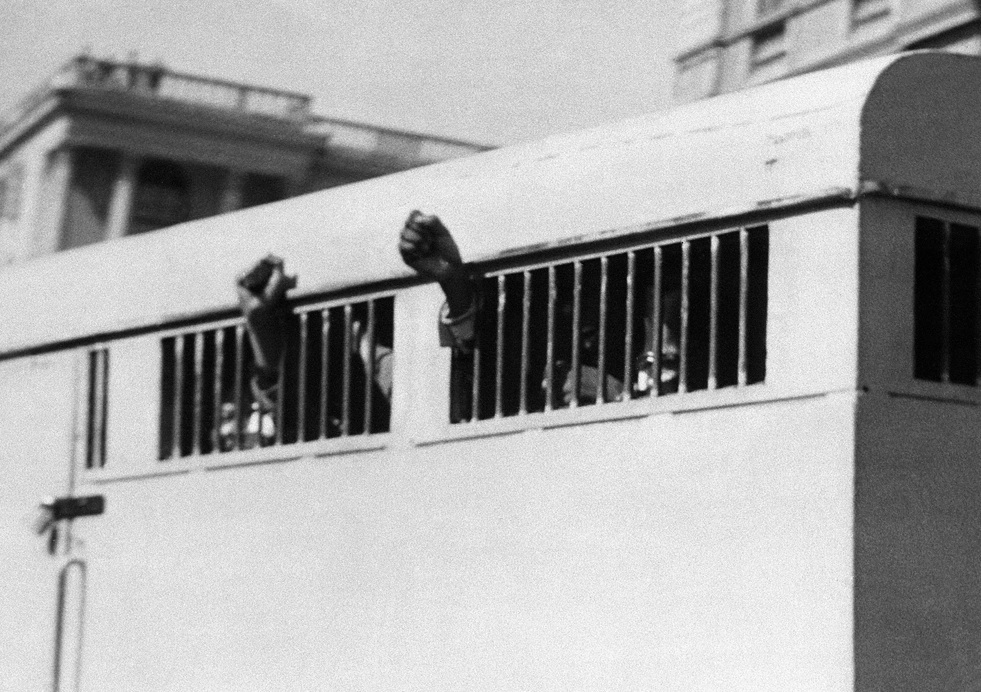

But of course there is more, for what makes the photograph distinctive is not the metaphorical wall so much as the extended hands that traverse the opening. Hands with opposable thumbs are distinctively human and here we see them as fragmented body parts. The fragmentation is not incidental. Typically the face is the visual marker of the liberal individual; absent such markings we don’t see particular individuals but rather social types, and thus the scene becomes something of an allegory for one dimension of the body politic as it negotiates the relationship between citizen and so-called “illegal” or “undocumented” immigrant. Viewing the image in this register invites us to imagine U.S. immigration and border policy as played out in something like the Theater of the Absurd.

The hand on the right extends from inside the cell door, so it is clearly marked as “other” and “dangerous,” but apart from being large enough to be masculine and appearing to be white, the only social marking that it reveals is a wedding ring, linking its bearer to a time honored social ritual and tradition. Were one to encounter this hand in any other situation it is unlikely that it would be seen as inherently alien, let alone precarious or threatening. The hand extending from the left is fully covered, a sleeve extending to the wrist and overlapping with a blue rubber glove, the two cinched by a watch strap. The glove is the sort that we see being worn by investigators at a crime scene or a chemical spill, both situations where it is important to avoid contamination. The overall impression, then, is that the arm and hand are hermetically sealed, and the implication here is hard to avoid: the hand on the left is protected from the presumably menacing or infectious hand on the right.

There is something altogether farcical about the relationship here and what calls it out is the piece of fruit being passed ever so tenderly from left to right as “dessert.” On the one hand (no pun intended), the offer of dessert—not just food or nutrition—is a humane gesture designed to provide some measure of pleasure to the person connected to the “othered” hand on the right; and yet, on the other hand, one has to wonder about extending such a gesture to an alien who is truly dangerous, so much so that any contact whatsoever would somehow threaten the well being of the person connected to the hand on the left. That one would make such a gesture recognizes a fundamental, ethical human and social responsibility that simply cannot be avoided or ignored, even when there are risks at stake. Neither walls nor borders can erase it. And even in our most paranoid state, it peaks through as an obligation that we have to our human brothers and sisters.

And so the point: the immigration problem we have in the U.S. is not, at its core, a matter of how to contain our borders so as to avoid making contact with alien others, as much as we might convince ourselves that such contact is risky, but rather to recognize the fundamental obligation(s) we have to extending human rights in as humane a fashion as possible to all who share our humanity. Once we allow ourselves to see that obligation and then commit ourselves to upholding it we will be better prepared to imagine how to negotiate the presence of immigrants within our midst and to produce policies that honor our very humanity without reverting to the theater of the absurd.

Credit: John Moore/Getty Images

0 Comments