Ezra Pound famously remarked in The Spirit of Romance that “All ages are contemporaneous.” This was not the temporal equivalent of a flat earth claim, but rather his announcement of what was to become one of the great poetic doctrines of twentieth century modernism. For most of us, however, the past is past. Sure, Faulkner knew better, and there are vital cultures of memory, but modernity is about an endlessly expanding future. Even as that dream has been steadily degraded of late, the incessant demands of ordinary life amidst a continual stream of news, weather, and sports continues to keep most of us living from day to day. The timeline isn’t quite so narrow as that of an Alzheimer’s patient, but American society might be suffering from a similar loss of temporal bandwith. Forced to live in a continually collapsing present, personality becomes brittle and fear can contaminate everything. For that reason, then, there actually may be good reason to see something closer to what Pound had in mind.

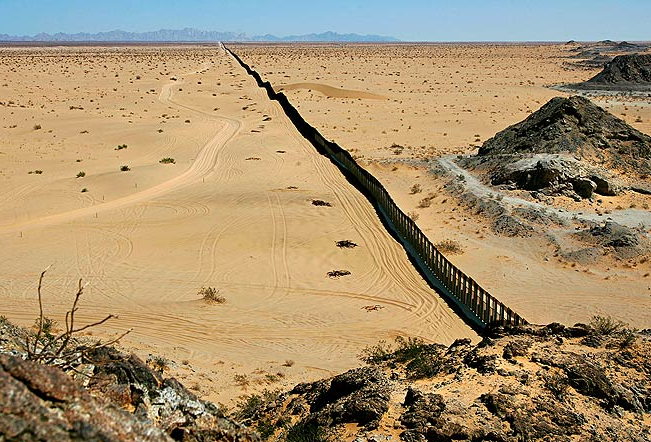

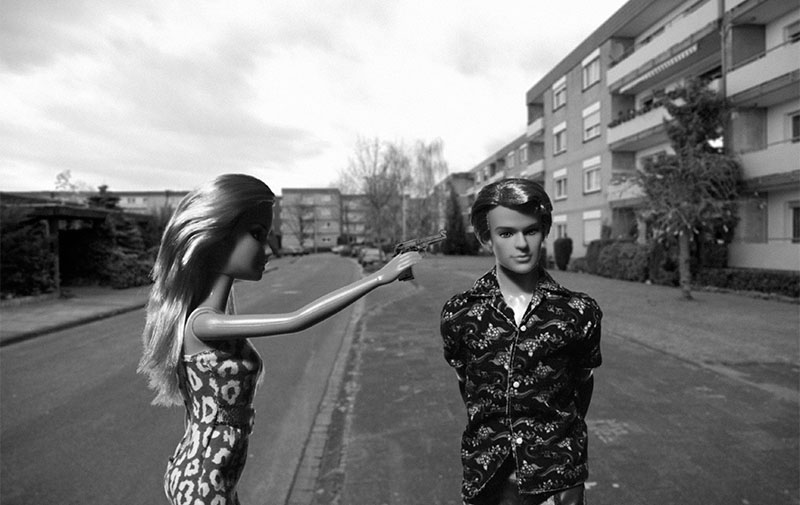

A month ago I posted about the peculiar return to medieval clothing and weaponry in security forces. I suggested that what may seem to be a superficial analogy could be documenting a regressive transformation of political power. Globalization, excessive capital accumulation, and other structural changes may be leading not to the march of progress, but rather to the breakdown of modernity itself. The photograph above supports that idea, except that now I’m looking at it while in a different mood.

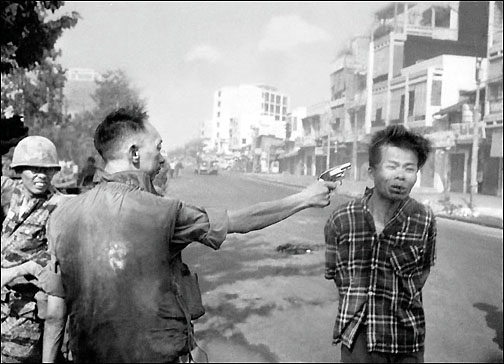

The medieval horseman rides through the modern street, almost as if he were riding out of and then back into the past. In the background, the signs of modernity are rather slim–primarily the diction in the graffiti. The steel fixtures in the foreground provide the more reliable assurance, as they literally frame the horse and rider. Fire seethes in the left of the frame, but it seems self-contained by the metalwork and lack of other material to burn. The tableau could be an artist’s construction, perhaps by one who had been reading Pound. Medieval past and modern present are contemporaneous: uncannily yet easily captured together in the artistic medium. At the moment the medium is photography, the art that traps any moment–but 1/500 of a second–in an eternal present that can be seen as it was endlessly, anytime, out of time.

Art does mirror life, however. The horseman really was there, and the photograph can remind us that time need not be linear, that the past need not be past, and that a medieval world may already be present among us. Modernity may be riven with ruptures where what was thought to be safely superseded continues to lurk, resurface, or reassert its power. These remnants of the past need not be the absolute opposite of modern time, as with the myth of eternal return, but rather something much more capable of displacing and redirecting the course of history.

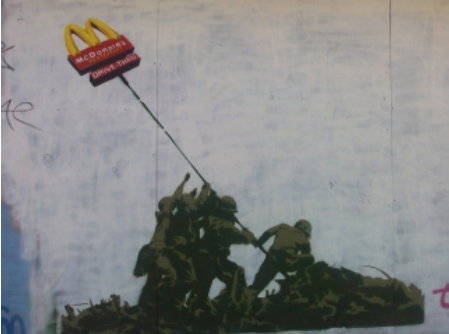

But I’m getting grim again. This post began, if that is the right term, with a commitment to enjoying contemporaneity, or at least appreciating how public arts could be restoring a sense of the past that is uncanny and provocative rather than conventional. Like this:

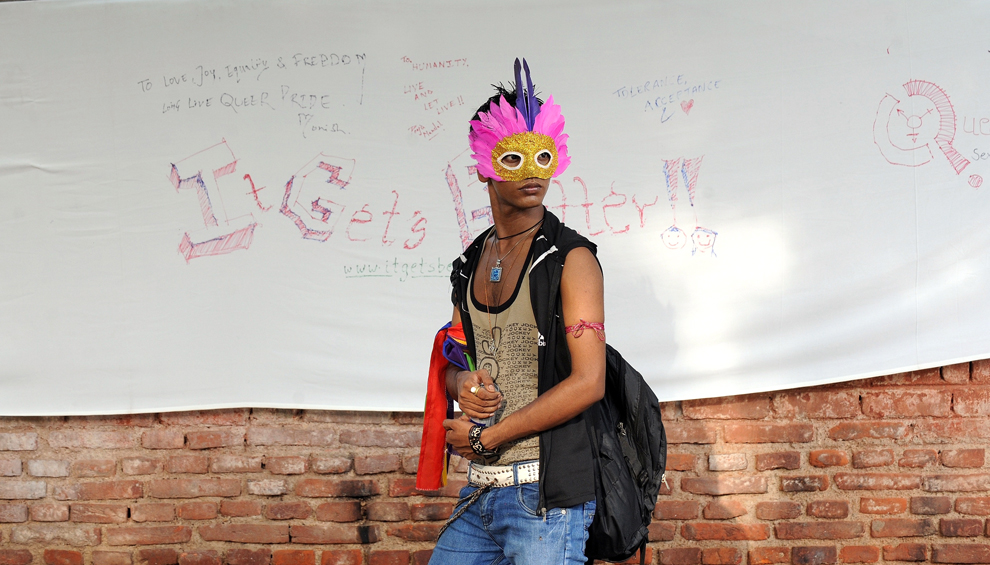

The caption placed him at the Gay Pride parade in New Delhi on July 2, 2011. I think he walked right out of Renaissance Italy. Again, the slogan in the background reminds us of the present, but otherwise he could have fit right in at Florence. And they would have understood that mask more than we can imagine.

Any photograph is another reproduction of modernity’s endlessly unfolding present, but this one also offers a glimpse into another time. Thus, the photograph itself is a tear in the modern fabric of time. And through that narrow aperture, we can see something eternal.

Photographs by Victor Ruiz Caballero/Reuters and Prakash Singh/AFP-Getty Images.