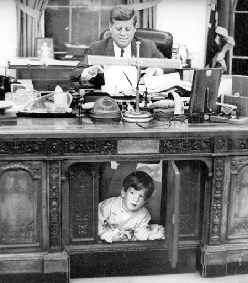

Can you name the location of this photograph? If you need a hint click on the image.

Even those who actually recognize the scene probably misidentify it. Most westerners would be inclined to say that it is Tiananmen Square, though it is actually Changan Avenue, which is a bit east of the square. On its face that small detail of misnaming would seem to be relatively unimportant, after all, what really matters was the event, right? And the iconic photograph nails that as a lone individual stands down a row of tanks. Of course, when we say “iconic photograph” we have a bit of a problem too since there are at least four different photographs that are commonly referred to as “the” photograph. But again, perhaps that too is just a trivial matter as each image is really quite similar and collectively they appear to confirm the relevant facts—a man, a row of tanks, a public thoroughfare, etc. So what if the four images are not identical to one another—if in some you have a close-up and in others you can see the wide street and bus, or if in some the man is carrying a bag in each hand, but in at least one he no longer has a bag in his right hand? What difference does it make? Maybe nothing.

Then again, perhaps it calls our attention to the ways in which photographs become reductive representations of places and events that can (and often do) direct (or misdirect) our attention and, subsequently, our memory. What was the dance between the man and the tank all about? Was it about a lone, heroic individual standing up against incalculable odds in a scene that might have been played out in the mythic American west with Gary Cooper cast as the man holding the bags? Or was it one small part of a mass, collective demonstration, a radically democratic (and potentially dangerous), grass roots revolution? Did that photograph inflect a liberal or a democratic moment? Perhaps the photograph above coaches an answer.

It is not hard to see this photograph as a visual quotation of the iconic image of the man and the tank. Taken from almost the identical vantage of the iconic photograph(s), it shares many of the high modernist aesthetic conventions of the original that make it easily identifiable to western audiences: It is universal rather than parochial (it could be anywhere in the world), it is geometric rather than organic (notice how the scene and all that it contains are disciplined by rigid angles and vectors), it is functional rather than customary (the street is designed to “move” masses of people from one place to another rather than to accommodate social interaction), and so on. But more, it is shot from on high and at some distance. The viewer thus looks down upon the scene with a degree of objective detachment that James C. Scott affiliates with “seeing like a state,” a panoptic vantage “that is typical of all institutional settings where command and control of complex human activities is paramount.” That the iconic photograph has circulated mostly (and almost exclusively) in the west is a clear indication of who is viewing whom, and who presumes cultural hegemony. But what is being naturalized here?

The template is framed in a figural dialectic defined by the relationship between “then” and “now.” And from this chronotopic perspective, what is different are the particular figures within the scene. In 1989 we had a showdown between the heroic individual and the authoritarian state, in 2009 we have the traffic and commerce symptomatic of a busy thoroughfare in any city in the world. What is important to notice is that in each photograph the anonymity of the actors remains intact, with this crucial difference: then they were defined as political agents caught in a struggle between good and evil, now they are seen as global consumers defined (as so often in the U.S.) by their cars. What was thus then cast for western eyes as a liberal-democratic revolution is now cast as a liberalized, global economy of undifferentiated, mass consumption. Liberalism, it would seem, is the trump card. Their present is our past … again.

That could be useful framing of the social order, as it animates the possibilities for trans-global identification, or it could reduce our sense of the possibilities for a global civil society to a neo-liberal economic hegemony disciplined by the narrow and limited conventions of late modern design. Its all a matter of what we choose to see and remember.

Photo Credit: David Gray/Reuters (For more on our consideration of the original “tank man” image and its various iterations and appropations see chapter five in No Caption Needed (the book) and posts here and here.)