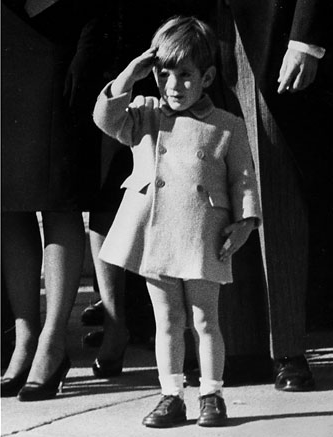

Last week I commented on the latest effort to discover the “true” identity of the kissers in the famous “Times Square Kiss” photograph. Reporting on such efforts is a fairly common narrative that follows along with the circulation of many iconic photographs. After all, most such photographs rely upon a certain degree of anonymity and when we encounter the anonymous our curiosity is piqued. Who is the migrant mother? Or that young girl at Kent State? Or the man standing in front of the tank in Tiananmen Square? And so on. Earlier this week Erroll Morris, an important documentary film maker, reprised the question raised last year (3/11/2006) in the NYT concerning the alleged identity of the man known as”Gilligan” in the iconic Abu Ghraib torture photograph:

Morris argues that the controversy demonstrates “how we make false inferences from pictures.” We think that he gets it wrong, or perhaps more to the point, he asks the wrong question and thus diverts attention from the very important range of ways in which photojournalism contributes to a vital and robust democratic public culture. Robert posted our response as a comment at the Times. We’ve reposted that comment below, but we also encourage our readers to attend to the continuing and very spirited and engaged debate on this topic at the NYT.

Posted at the New York Times, August 16, 2007:

Errol Morris’s essay is one example of his claim that “We do not form our beliefs on the basis of what we see; rather, what we see is determined by our beliefs.” His critique of the Abu Ghraib story depends on several axioms of Susan Sontag’s critique of photography. Unfortunately, each one of them is at best half true.

1. Photographs corrupt moral response by substituting the image of the victim for reality: “The no longer anonymous Hooded Man became a national news story – not because he was a victim of torture and abuse at Abu Ghraib but because he was in a famous photograph.”

2. Photographs corrupt our knowledge of reality: “Namely, the central role that photography itself played in the mistaken identification, and the way that photography lends itself to those errors and may even engender them. . . . photographs attract false beliefs – as fly-paper attracts flies.”

The basic problem with both of these ideas is that the critic is attributing to photography what is true of all representation, verbal as well as visual. Think about it: can you depend any more on written accounts of reality? If so, I have a bridge to sell. You don’t have to spend more than ten minutes in a court of law to see that writing is highly suspect. Newspaper reportage is partial at best while details often are mistaken; government reports have an additional set of problems, scholarship is subject to paradigmatic restrictions, and so forth and so on. The most false, dangerous, immoral, and harmful publication in the world is not a photograph, but a book: The Protocols of the Elders of Zion.

And for all that, writing, like photography, is a remarkable tool for learning about, knowing, and navigating through the world. If left only to what we see directly, we would know and care about very few people (and no more accurately, by the way: eyewitness testimony is notoriously bad evidence). That we care about victims because we see images of them—or read about them, say, by reading the Diary of Anne Frank—demonstrates that we can expand our capacity to care through our use of the public media. Nor are we trapped in our representations. In fact, belief and experience work both ways: prior belief shapes perception, yet human beings, like other animals, continually adjust their conception of the world based on what they observe.

That said, I’ve gotta like the attention Morris pays to iconic images such as the photo from Abu Ghraib. (Full disclosure: I’m co-author with John Lucaites of No Caption Needed: Iconic Photographs, Public Culture, and Liberal Democracy, and John and I maintain the blog No Caption Needed.) The debate about identifying the specific individual in the Abu Ghraib icon is one measure of the photo’s status: similar efforts are made with every iconic photo. At least two issues need to be noted here: one is that, although indifference to the specific individual in the photo could be a moral mistake, the moral testimony of the photograph requires only that someone is there, not any one person. Morris makes the right distinction but gets things backwards when he claims, “Now we are talking about reality – not about photographs.” No, we are talking about photographs, specifically, about a photograph’s documentation of torture. As with other iconic photographs, the image’s moral power depends on the anonymity of those in the picture. We empathize because the person could be anyone, not because it is this or that individual. The photograph of the napalmed girl running down the road in Vietnam was moving not because it was a picture of Kim Phuc, but because it was a picture of a girl much like children you have known.

This is why I can’t get excited about the stories of who was in the photographs from Iwo Jima, Vietnam, Kent State, or Abu Ghraib. These narratives usually serve to domesticate the image, to transform its powerful call for public action into a feel-good story about private life. Barthes said the photograph could be mad or tame. Locating the individual in the iconic image, however accurately, only tames the photograph and perhaps the public as well.

Photo credit: Shawn Baldwin/New York Times

0 Comments

![]()