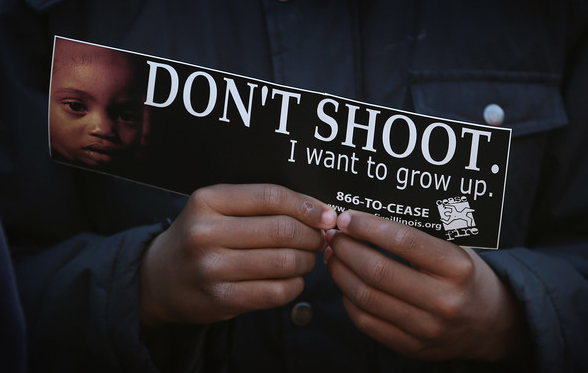

We have written here (here, here, and here) and elsewhere about the photojournalistic penchant—indeed, we are inclined to call it a photojournalistic convention—to produce photographs that feature hands (and feet). Often such images feature the fragmented human body, emphasizing the hand (or the foot), and thus diverting attention away from the face. The face is, of course, the chief marker of the liberal individual and by deemphasizing it notice is directed away from the particular individual to a more universal(izing) “human feature. The inclusion of the face in the image above is something of an exception to the typical convention that makes the point, as the caption to this image calls attention to an Argentine Court’s ruling that “Sandra,” an orangutang who has spent 20 years in a Buenos Aires zoo, is a “non-human person which has some basic human rights.” Humanity here trumps personhood.

The photograph is part of a Big Picture slide show titled “Hands in the News.” According to the BP, “Hands tell stories. They are functional and they have the power to communicate emotions…. Represent(ing) hope, communication, power, connection, and longing.” All of this is true. But there is more. For such photographs don’t just invite us to see the “hand,” but rather to see “with the hand,” and as such it activates a traditional way of thinking about sociality and politics (e.g., the body politic) that is adapted to conditions of public representation: it is fragmented rather than organic, realistic rather than idealized, and provisional rather than essentialist. Most important, the dismemberment of the body implies a body politic that is no longer whole yet still active and engaged.

In short, the image of the hand (or the foot) as a bodily fragment signifies the distributed body of modern social organization, the pluralistic body of modern civil society, the multicultural body of a transnational—or as with the photograph above, transhuman—public sphere. This is the body that resists the abstraction and political symbolism dominating official discourse, but always indirectly, through figures of embodiment that are already dismembered. This is a rhetoric of bodily experience, but not the personalized experience of identity politics or the faux intimacy of infantilized citizenship. These images have proliferated when official authority is already discredited, and they are used to both contest that authority and finesse the problem of maintaining public legitimacy.

We should attend to them with care, not just as a stylistic affectation or an instance of cultural kitsch, but as an important convention of a powerful public art that invites us to see and be seen as citizens in the broadest way possible.

Credit: Natacha Pisarenko/AP