The image below is a not very good photograph of a tar ball on the beach at Dauphin Island, Alabama. Despite the many more dramatic shots of the Deepwater Horizon oil spill, this low-grade photo of a mundane object might be the better image of things to come.

Tar balls from this big spill will be washing up for years, but that’s only part of the story. What I envision is that the beaches will be cleaned and booms strategically placed and signs put up for the kids–“playing with the tar balls may be hazardous to your health”–and generally the Gulf will get back to normal. That is, to a new normal that is a somewhat degraded version of what was there before. Boats will still launch for both commercial and sport fishing, although now they will be working more tightly zoned catch basins (or not, and risk the fines that will be part of loosely enforced regulations). The oil companies will continue to place drilling platforms throughout the Gulf, although now with two blowout preventers instead of one. The damage suits and insurance claims will keep a legion of white collar workers driving to work in cars having everything but good gas mileage, and life will go on.

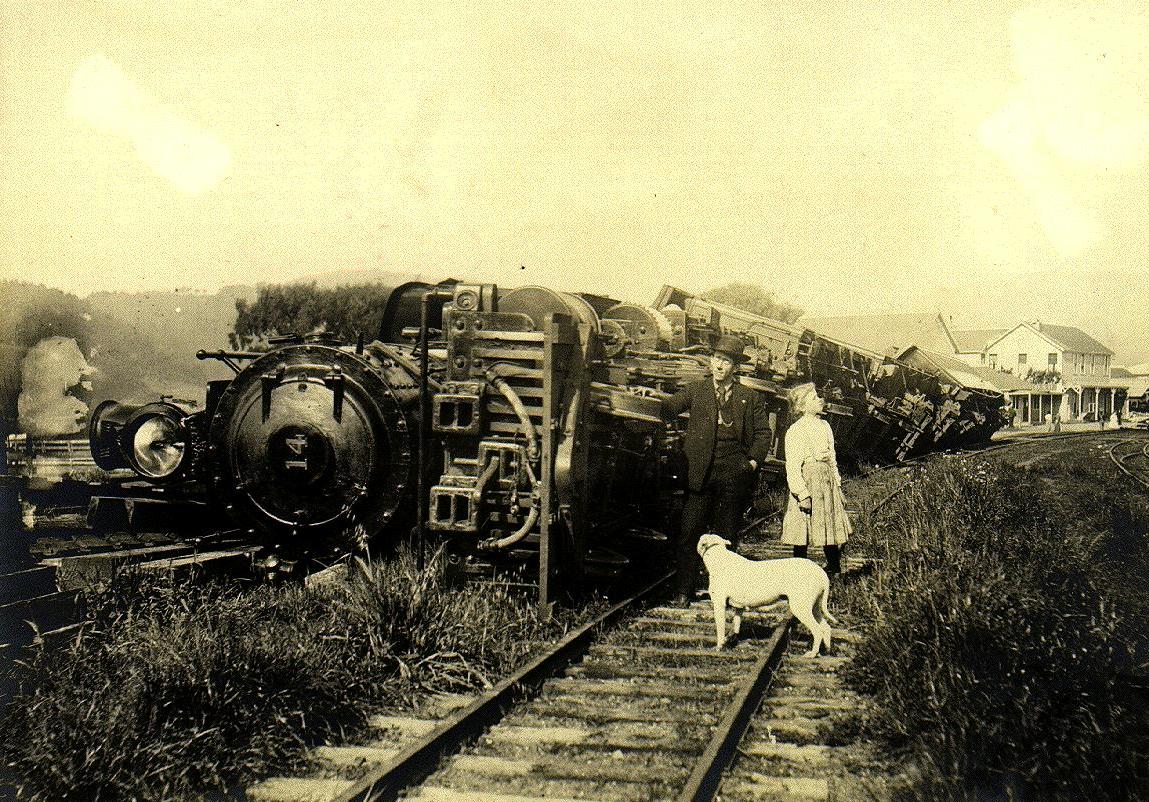

This new normal is already evident in photos of vacationers and clean-up crews on the same beach. What was the couple on the blanket supposed to do, cancel their plane reservations? This continuity is hardly limited to the beach: New Orleans is still struggling to recover from the Katrina disaster, but, hey, the Saints won the Super Bowl, and so the city puts on a good face while quietly adjusting to a smaller population and neighborhoods still a long way from recovery.

One reason I fear for my country is that there seems to be so little commitment to replacing damaged infrastructure with state-of-the-art public works. The stimulus money was largely used for patch jobs; that may be expected when you have to spend money quickly, but there was little talk of what might have been: a grand program of civic renewal. So much of the US currently is just being maintained–and now vast swaths of the suburbs have to be added to that list as they, too, are aging.

During the Great Depression of the 1930s, the New Deal wasn’t used to return the country to 1928. After World War II, the Marshall plan wasn’t used to recreate the Europe of 1939. The Federal Aid Highway Act of 1956 didn’t merely repave existing roads but went on to create the Interstate Highway System. In each case, the money was used to get back to better. The same needs to be done in the US today.

The most obvious cases are in response to disasters such as the big oil spills, but that is only part of the challenge. There also are the slow moving economic disasters that have been destroying the cities and towns in the industrial Midwest and elsewhere. (Detroit wasn’t hit by a hurricane, but it’s in worse shape than New Orleans.) The same holds even in relatively prosperous sections of the country: bridges, rail lines, subways, parks, pools, beaches, boulevards–there is so much in the US that could look a lot better. Add to that the need for redesign and serious negotiation of complicated structural problems (say, such as supporting recreation, fishing, and extraction industries in the same ecosystem), and there is more than enough work to be done.

What is missing, however, is political will and a genuine commitment to the future. Both deficits can be traced to the Republican hegemony since Ronald Reagan’s presidency. Reagan rebranded government as the problem while proclaiming that the marketplace would provide nothing but solutions, and now several generations have become habituated to the degraded environments that are the result of that ideology.

And so here we go again. The usual response will be to clean up the worst of the mess and then make do with a bit less than you had before. But why settle for that? I’d like to think that the time is coming when, instead of getting back to not very good, the country can get back to better.

Photograph from The Huntington Post.

Cross-posted at BAGnewsNotes.