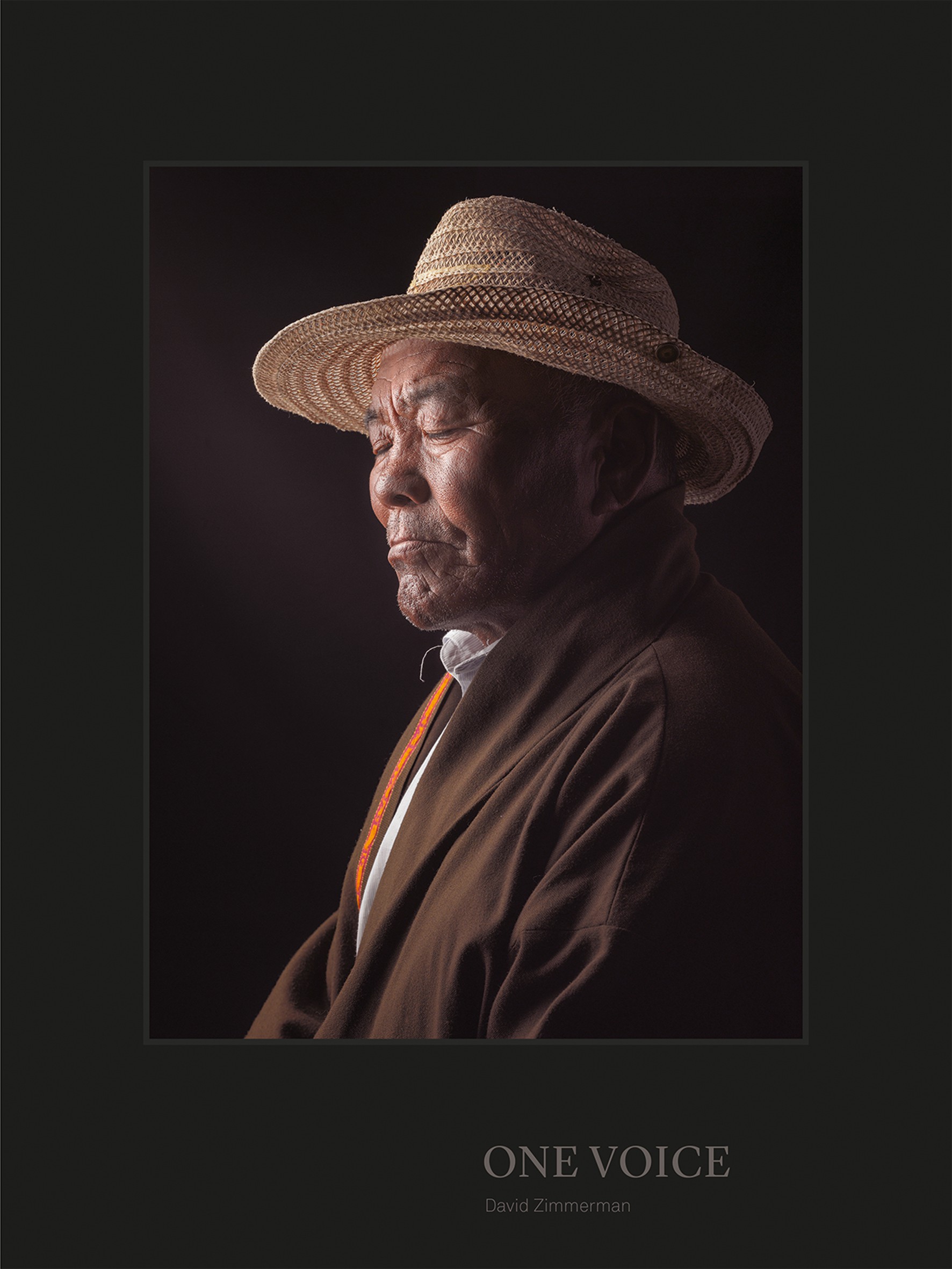

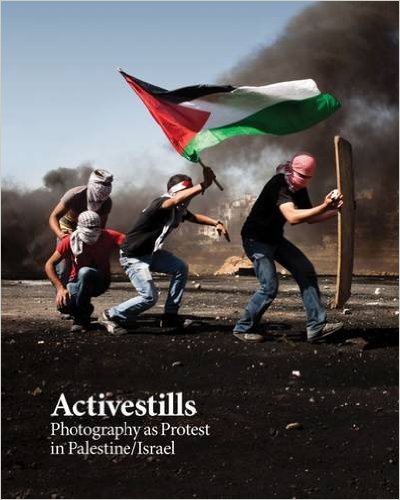

It is becoming clear that photography is undergoing a paradigm shift. Many things will remain the same, and perhaps look the same at first glance, but assumptions, attitudes, and ideas are nonetheless changing. So John Lucaites and I argue in The Public Image, and one of the most recent examples to come to hand is a book that was published at the same time as ours. Activestills: Photography as Protest in Palestine/Israel presents some of the work of the Activestills photography collective along with short essays, interviews, and statements to provide personal, historical, and theoretical context for the project.

The collective is a group of Israeli, Palestinian, and international photographers who are dedicated to supporting progressive social and political change in Palestine/Israel. Their work focuses on “various topics, including the Palestinian popular struggle against the Israeli occupation, rights of women, LGTBQ, migrants and asylum-seekers, public housing, and the struggle against economic oppression.” They work as documentary photographers, but on behalf of justice rather than press neutrality. They distribute their work through mainstream, alternative, and social media, and as free exhibitions in those places where the photos were taken. They sign their work collectively, maintain long-term relationships with the communities where they bear witness, and strive to “shape public attitudes and raise awareness on issues that are generally absent from public discourse.”

The collective also is attempting to open up the visual field to create new public encounters. In place of showing victims, they feature agency. Instead of trying to capture the decisive moment, they track the slower, more insidious forms of violence. Rather than rely on icons, they develop an archive, and foregoing much of the iconography of protest (except on the book’s cover), they follow the odd, often chaotic angles of intimacy amid conflict and its devastating aftermath. And rather than rely on the supposed power of the image to compel moral response, they assume that it has to work within complicated processes of interpretation.

The result is not eye candy, but it’s not another set of atrocity photos, either. Alternating between two-page single image displays and many, many smaller images–often seven to a page–the viewing experience can be frustrating. Even the large images are immersive: tightly copped, or with any background indistinct due to tear gas or desert topography, you may not know where you are unless you read the fine print. The small images seem to call for a connoisseur, except that the optic is fundamentally banal–ordinary people, places, things, lighting–and the fact that time and again these are scenes of violence, destruction, and loss.

Activestills does not make spectatorship easy, but it is made worthwhile. By working through the volume, one’s sense of inside and outside begins to shift. Not to create the illusion that “you are there,” but to realize that violence extends beyond spasms of direct conflict to become a system of domination pressed into the fabric of life. Likewise, instead of looking for one image or signature event, you begin to appreciate the weight of the archive, the judgment of history, the profound need to work day after day, person by person, until justice and solidarity prevail.

This commitment is echoed in the essays in the volume, which also make direct contributions to revising the discourse on photography. The break with conventional wisdom and implications for the future of photography are sketched deftly in Miki Kratsman’s Foreward and in the Introduction by the editors, Vered Maimon and Shiraz Grinbaum. Ariella Azoulay identifies how Activestills is developing a civil language of photography to counter the imperial discourse of differential distributions. Haggai Matar and Ramzy Baroud outline the project’s relationship to the media environment and the political environment, while Simon Faulkner discusses the role of the exhibitions on the street. Vered Maimon explicates the shift in modality from representation to performance, from the indexicality of the image to the collective production of belief and affective community. Ruthie Ginsberg and Meir Wigoder identify key shifts in temporality, i.e., from “what was there, then,” to “being there now” and signifying potential futures. Sharon Sliwinski identifies the damning potential of spectatorship to reinforce the condition of standing “before the law”–as in Kafka’s tale, forever locked out of the institution of justice–but she does so to reaffirm the role of the public image in imagining a just political community.

These ideas acquire personal texture in the interviews and statements by photographers and other activists, whose understanding of their work, individually and collectively, reminds us of what may be the most important lesson of all: whatever the technology, artistry, or means of distribution, photography at its heart is an encounter with the world. And even, perhaps, one means for achieving a better world.

2 Comments