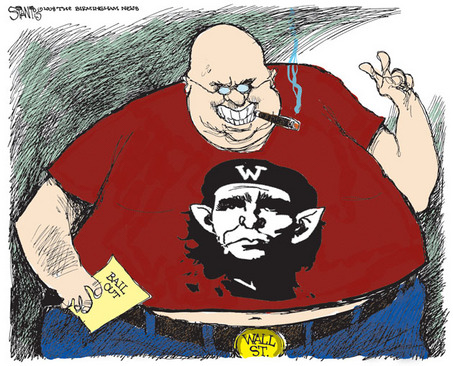

The breakdowns and bailouts in the financial markets have created sky-high levels of fear, anger, more fear, and more anger. As the Dow drops, anxiety spikes. The situation is awful, dire, disastrous, catastrophic–a maelstrom of panic, collapse, more panic, and further collapse as investors act like crazed victims piling up against a door in a theater that has caught fire.

Don’t think that I had my money in CDs. I’ve been nailed badly and the prospects are not good for my family. But somehow, everyone needs to take a deep breath and exhale. For all the talk of pain, the term remains a metaphor for many of us. And the panic is a symptom not only of the obvious problems but also of what happens when a society becomes a market society instead of a society with a market economy.

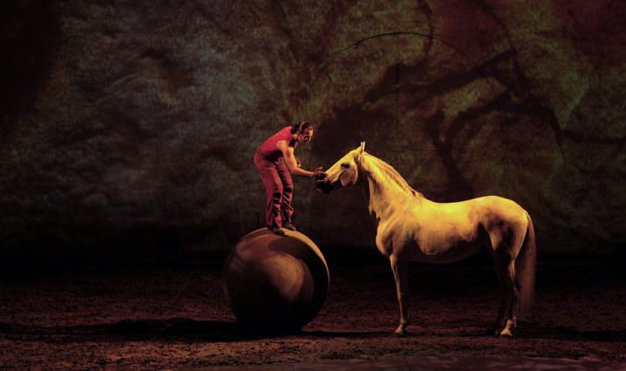

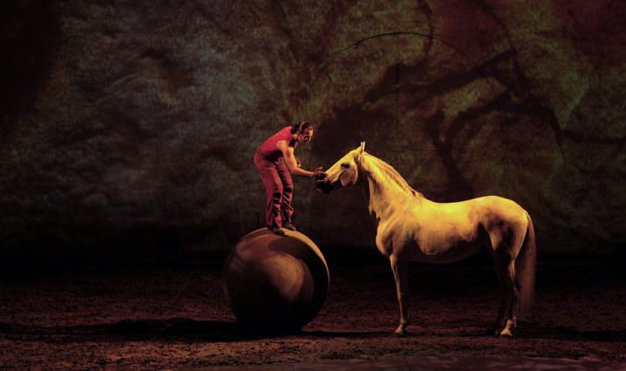

If a photograph can help us regain a sense of balance, it might be this one:

The caption at The Guardian tells us that we are looking at a man performing with a horse at the Cavalia equestrian show in Lisbon, Portugal. The horse will be exhibiting superb training, but the roles almost seem reversed. The man looks like the lesser animal, almost like a monkey who has been trained to do tricks on the big ball. By contrast, the horse seems the epitome of nobility, a superior being who only has to show up to dominate the scene. He is the standard by which the man will be judged.

Perhaps this seeming inversion of a natural order appealed to me because of the financial world being turned upside down, and because of my wish to regain a sense of balance. And the scene is about balance–more specifically, about repose, with balance one means to that end. Indeed, the man could be a metaphor for the markets, as he balances precariously (however skillfully) on a globe than is at once unified and capable of punishing any sudden shift in his stance. Above all, however, it is something different from the madness of the markets. Sure, they will have sold tickets to the show, but for a moment a man and a horse stand in perfect equipoise. The man is on top of a small world, but not to get rich. Communion with the horse is more important than that. The sense of ritual harmony runs deep; Confucius would say that this sense of things is essential to restoring balance in the individual and the state.

I could end there, but there is need to go a step further. Repose in a theater may be too easy. The real test is real pain. This is Childhood Cancer Awareness Month, and observance has included this beautiful portrait:

The caption at The Big Picture says, “Nathan Gentry, age 6, sits by a window overlooking New York City traffic on September 8, 2006.” Nathan died after months of painful treatments. Although trapped in a disease that most children, thankfully, do not experience, Nathan captures so much of the vulnerability of childhood and the profoundly precious quality of life itself.

This also is a picture of repose. He is experiencing, it seems, a moment free of pain, of quiet reflection on the scene outside the window. And the scene is outside: the glass walls him in as much as it lets him see, and the outer world has shrunk to that small portal. Outside we can see scaffolding, and so he is looking at a building that will be sustained, though he cannot be. His repose comes not for keeping everything in balance, but from putting himself in relationship with what remains. He asks–and takes–nothing but a moment of peace. It seems that he has already learned how to live with less. Obviously, that is something many of us have yet to learn.

Photographs by Nacho Doce/Reuters and, via The Big Picture, Susan Gentry (©), who asked for a link to the Children’s Neuroblastoma Cancer Foundation.

0 Comments